Alex Chambers: Thank you so much for doing this, Avi, I really appreciate it.

Avi Forrest: Yeah, just happy to help.

Alex Chambers: Alright, so you've got everything you need together?

Avi Forrest: Yes, I do.

Alex Chambers: Okay. Great, well I'm going to head off, leave you to it.

Avi Forrest: Thanks. Okay. Listeners, Alex has been working super hard lately, and so he can take a small rest, he finally let me post an episode. But the thing is, I don't actually have anything. I'm sorry, okay? I just kept procrastinating and playing Pokémon and it just snuck up on me. Right, what can I do for an hour? Let's see. Okay, there's some books around here. Ellie Engel Saves Herself. Shoot, we already did an episode on that.

Avi Forrest: This could be something. Tales by some guy named Erasmus Gould. Worth a shot, I guess. There's all kinds of crazy stuff here. Aliens, werewolves, witches, secret foundations. And I'm sure I'll find some way to tie this all up. I don't know, some interview with like a professor or something. Okay, this one's called Skalla Grímur. In ancient Norway, around the year 850, there was a man named Ulfr. Ulfr's a smart, well connected farmer--

Alex Chambers: ...smart, well connected farmer. He's doing well for himself and people admire him. But there is a bit of a problem.

Adrian Whitacre: Everyone says about him, that every day, towards the evening, he grows bad tempered and you don't want to speak to him or cross him in the night.

Alex Chambers: It's okay though. He goes to bed early and gets up early. Still--

Adrian Whitacre: People called him Kveldulfr which means night wolf. And they said that he was a shape shifter, and he was very shape strong, or very shifty.

Alex Chambers: I mean, that's what people said.

Adrian Whitacre: But who knows?

Alex Chambers: In any case, for a long time, Ulfr’s been feuding with the King of Norway. Eventually, the feud culminates in this one big battle. Kveldulfr and his son and their men decide to attack one of the king's big ships. There are over 50 men on the ship.

Adrian Whitacre: And so, together, they board the ship. And Kveldulfr, in particular, when he boards the ship, he seems to go into, like a frenzy. He becomes frenzied like a wild animal. And some of his men, they also go into this frenzy, and together they sweep from one side of the ship to the other. They're unstoppable. No-one can touch them. And together, they kill all 50 men and they throw them into the sea, leAving only a couple of survivors to send the message.

Alex Chambers: It had been said of those men who were shape shifters, that they go berserk.

Adrian Whitacre: And they become so strong in this state, that they're completely untouchable.

Alex Chambers: But once the battle frenzy passes, they lose all their strength.

Adrian Whitacre: And this is what happened with Kveldulfr.

Alex Chambers: So he calls over his son and his men, and says, "I don't usually feel this worn out. I'm completely drained."

Adrian Whitacre: "This might be the end for me?" And he goes into such a state of weakness that he passes away soon after.

Alex Chambers: Years go by. Because of the bad blood between him and the King, Kveldulfr's son, Skalla Grímur, has to leave Norway and go to Iceland.

Adrian Whitacre: He sets up his own farm there in Iceland, and he starts a family.

Alex Chambers: He has two sons, one of them is Egil. One day, Skalla Grímur and Egil, and one of Egil's friends, [PHONETIC: Thord, are out playing a ball game.

Adrian Whitacre: And Egil and his friend Thord are on one side, and Skalla Grímur is on the other.

Alex Chambers: Egil and Thord are doing pretty well. They're definitely ahead. But the game goes into the evening. It starts to get dark.

Adrian Whitacre: And suddenly Skalla Grímur now has the upper hand. He seems to be getting stronger and stronger, as the sun sets and it gets darker. And he's also getting more violent. The game is getting more aggressive. It's getting more dangerous.

Alex Chambers: It only gets worse. Suddenly, Skalla Grímur grabs Thord and throws him to the ground.

Adrian Whitacre: So hard that it crushes him.

Alex Chambers: And he dies.

Adrian Whitacre: And then, he turns on his son. He turns on Egil.

Alex Chambers: And he's coming at him, driven by this rage that somehow grew out of a ballgame, when a servant woman appears at the top of the hill. She was Egil's foster mother.

Adrian Whitacre: And she also knows a little bit of the magic parts. She's a full [INAUDIBLE]. She's very wise in the ways of magic. She's very crafty.

Alex Chambers: She shouts at Skalla Grímur.

Adrian Whitacre: "You are shape shifting now Skalla Grímur," or maybe a better translation would be, "You're becoming an animal Skalla Grímur, at your son."

Alex Chambers: Skalla Grímur hears her and turns from Egil and goes after her instead. She runs toward a cliff, and rather than letting the monstrous Skalla Grímur tear her apart, she leaps off the cliff into the water. And Skalla Grímur throws a huge rock down on top of her.

Adrian Whitacre: Neither she nor the giant boulder are ever seen again.

Alex Chambers: Egil and his father don't say a word to each other about what just happened.

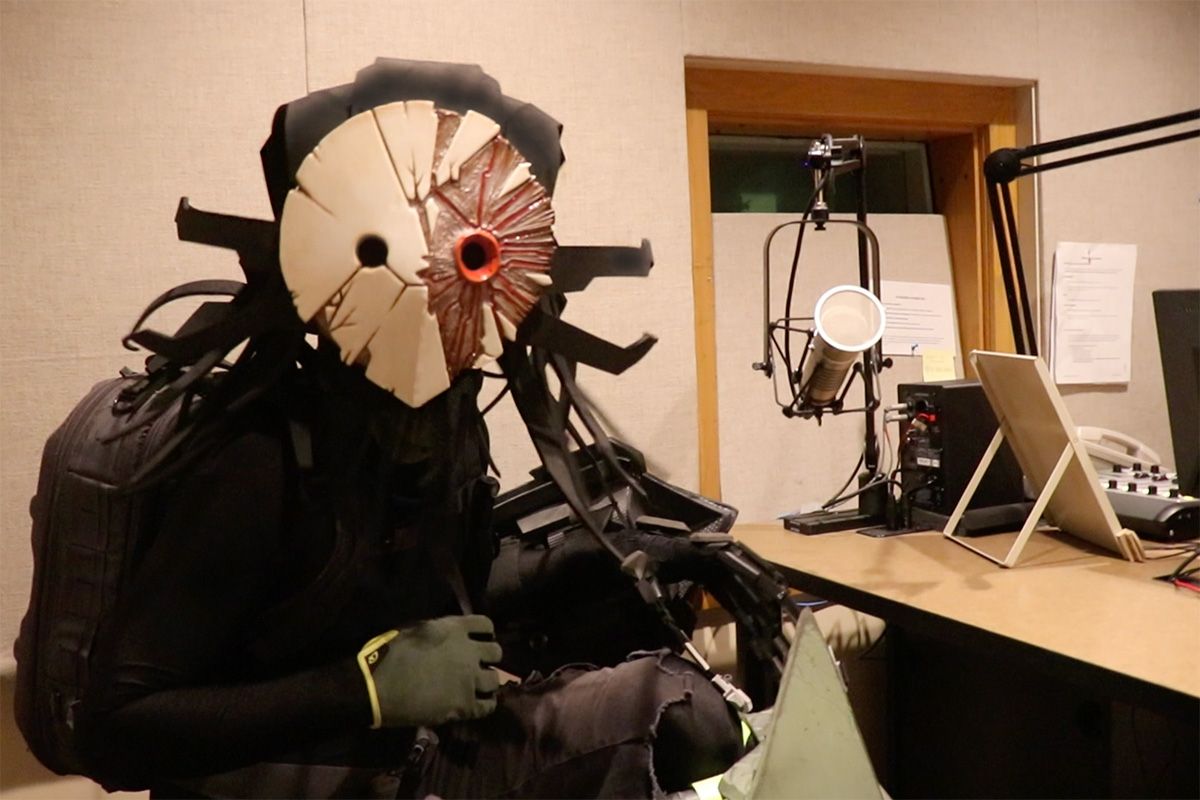

Avi Forrest: And in fact, they don't speak to each other at all for months afterward. Jeez, that's spooky. When was this book published? Whatever. This next story is called the Skeleton Harvester. The creature loped down the sidewalk, drawing the eyes of each pedestrian.

Reilly Donaldson: I would say, like, the number one reaction is what--

Unknown female: [LAUGHS] Aah.

Unknown male: What the hell?

Unknown male: Someone.

Unknown female: Oh. [LAUGHS]

Reilly Donaldson: Like people screaming, "What the--?" or like, asking "What is that?"

Unknown female: Sleep paralysis demon I think is the best way to put it.

Unknown male: That's so scary, and you shouldn't do that anymore ever again.

Reilly Donaldson: People always think that I'm using a voice modulator, and I'll usually point at my throat or at my chest and continue to gibber at them in skeleton tongue. [LAUGHS] So they understand that no, that's me.

Unknown female: Tall and scary and--

Unknown male: [FOREIGN DIALOGUE]

Unknown female: Kind of robotic.

Unknown male: For me, I'd describe him as the bodyguard.

Unknown male: You're my soul animal.

Unknown male: Living art. Yeah.

Unknown female: Yeah. And so friendly.

Reilly Donaldson: So I have always sympathized with the monsters in monster movies [LAUGHS] just like what? But, at least it's an alien. Like dude, you have no respect [LAUGHS] for the first time you're carrying extraterrestrial life.

Avi Forrest: Meet Reilly Donaldson. He's around seven feet tall with a pale owl shaped face. Things that look like feathers plume from his head, and he carries a stash of canisters that help him breathe in our atmosphere. Reilly likes to take walks around Bloomington every so often. You could say he's a people watcher. So, here we are, on a walk in the night.

Avi Forrest: Oh. The dogs don't seem to like it.

Avi Forrest: During the day, Reilly works for IU's university collections as an exhibition assistant/preparator. He makes the bases, hangers and stands that support various works of art. He also likes movies, and TV shows, especially science fiction and anime.

Reilly Donaldson: Stuff like alien, aliens predator. When I was really young, before I could watch the scary stuff, you know, I loved movies like ET. Short Circuit.

Avi Forrest: Basically, giant space robots with lasers and highly intelligent intergalactic aliens, also with lasers. Which I guess makes sense, given that according to him, he's a couple of million years old.

Avi Forrest: So, wait, so where are you from?

Reilly Donaldson: [STRANGE LANGUAGE].

Avi Forrest: Pointing to the sky--

Reilly Donaldson: [INAUDIBLE]

Avi Forrest: Reilly is from two places. He was born in Indiana, which is on earth. And the other is sort of a long story.

Reilly Donaldson: The Null species, the Skeleton Harvester is an alien known as the Null species. And they are unfathomably long lived super intelligent, telepathic aliens.

Avi Forrest: Instead of Reilly, you would probably know him as the Skeleton Harvester, named for the calcium it needs to survive.

Reilly Donaldson: Bones, super high in calcium, the creature has been seen dragging, like bones and dead corpses, not human corpses, but deer and animals.

Avi Forrest: Don't worry, he's no threat to humans.

Avi Forrest: I'd ask for advice, but I don't know, advice in your native tongue.

Reilly Donaldson: Eliminate greed, eliminate war.

Avi Forrest: So, why does Reilly enjoy strapping on stilts and scaring pedestrians? Well, the short answer is--

Reilly Donaldson: I'm an adult and I live in America, and so I'm gonna wear what I want. [LAUGHS] And if that means I wanna be a cryptid and walk around, and as long as I'm not hurting anybody, then tough.

Avi Forrest: There's also a much longer response. Let's think of it this way. Reilly plus costume equals Skeleton Harvester right? That would make sense as sensical as a millions of years old alien can be. But, how do I say this? This is all much less A to B. So, can you put into a percentage of like you as a whole? What percentage is Skeleton Harvester?

Reilly Donaldson: Mm. At this point, probably-- [LAUGHS] it's getting close to like 50:50.

Avi Forrest: Reilly is the Skeleton Harvester, yeah. But the Skeleton Harvester is also Reilly. Like the two sides of a coin.

Reilly Donaldson: A lot of big religions talk about everlasting soul and stuff like that. I don't particularly believe in souls. I don't believe that souls exist. I believe that humans are "intelligent mammals."

Avi Forrest: Reilly describes himself as a trans-humanist, which is basically improving humanity with technology.

Reilly Donaldson: So from like full synthetic humans to augmented humans, to hybrid humans with, you know, whatever DNA you want spliced into you. If you want some extra glowy bits, you can get some cuttlefish DNA spliced into you. And you could have some bioluminescence in your skin, which would be cool.

Avi Forrest: You can't really get cuttlefish DNA in 2024. At least not in the mid-west. But Reilly was drawn to the next best thing.

Reilly Donaldson: All of the sci-fi anime that you could probably mention. Sense of humor comes from stuff like Ghostbusters and the Goonies. So I'm like super into this goofy, weird parody, and just like fun for fun's sake.

Avi Forrest: He got interested in art, and sci fi and anime. And manifesting his futuristic dreams into Styrofoam and cardboard.

Reilly Donaldson: Even before I was in college, I was scaring kids at my mom's house here in town, in her neighborhood, like every year for Halloween. And it became a tradition and we'd do the yard up really crazy, and I would start making props and stuff for the yard. So I started with, you know, carving EPS foam and making your own tomb stones super easy. You know, I went to IU, and just took as many art classes as they would let me take basically. [LAUGHS]

Reilly Donaldson: And loved the creative freedom of sculpture. I loved that I could go into sculpture classes, and the teacher was like, "Make what you want, and justify it."

Avi Forrest: Trans-humanism is also like--

Reilly Donaldson: As lovely as the human form can be and as great as it can be, I realize its limitations. And I can see those limitations. I see the potential for technology to help us supersede those limitations and become something more than human.

Avi Forrest: Have you ever thought about what it means to be a person? To be this strange little animal that's walking around, a dent collection of dust that's hurtling through space?

Reilly Donaldson: Sentience is a strange biological loop, and our brains are nothing more than the most sophisticated biological computers that we have encountered.

Avi Forrest: Does that make you feel trapped? Cornered into a strange little creature scuttling around the surface of an even stranger planet?

Reilly Donaldson: I don't particularly think that there's souls or heaven or hell, or afterlife. So I think it's vitally important that [LAUGHS] we make the most of our very limited time on this earth. [LAUGHS] At most, you know, we got 80 to 90 years. If we're lucky we get a hundred, if we're super lucky and we're healthy. So, we have that much time to impress upon others around us the importance of using that time valuably and in a way that's positive for people around you, people in your life, and for yourself.

Avi Forrest: I think we can all appreciate feeling stuck. Stuck in a job, a hometown, the closet. So we have stories, we have video games, music, books, giant robots fighting for alien supremacy. And we have cryptids, like Reilly .

Reilly Donaldson: People always ask "Why?" I'm like, "Why not?" [LAUGHS] That's like my number one comeback. "Why not?" [LAUGHS] I'm hAving fun. I'm not hurting anybody. I'm getting great exercise.

Avi Forrest: The reporter turned around for one last question.

Avi Forrest: Do you have any last words I guess?

Reilly Donaldson: [STRANGE LANGUAGE]

Avi Forrest: Love and peace. Thank you, she said, as she walked off into the night.

Avi Forrest: And the reporter was never seen again. Okay, that's kind of dark. Why do we even have this? You know what? Content is content. This next one's called Katla and Geirrid. Once, way back when, there were two rival witches.

Alex Chambers: ...two rival witches.

Adrian Whitacre: Their names are Katla and Geirrid.

Alex Chambers: They're neighbors.

Adrian Whitacre: And there's a young student who wants to learn from Geirrid. He goes every day to her house, and takes lessons.

Alex Chambers: But to get to Geirrid's house every day, he has to pass Katla's house.

Adrian Whitacre: And Katla is a much less popular person. She's harder to get along with, people don't like her. She's difficult.

Alex Chambers: And every day when he passes Katla's house, she comes out and tries to convince him to be her student.

Adrian Whitacre: And not go on to Geirrid's house.

Alex Chambers: Katla's argument to the student isn't just about curriculum. There are sexual overtones too.

Adrian Whitacre: She'll say, "She's an old woman. She, you know, can't give you what you want," and [UNSURE OF WORD] says, "Well you're an old woman too." [LAUGHS] And just goes right on by.

Alex Chambers: Then, one night, the young student is on his way home from Geirrid's house. Katla comes out again, and warns him that he'd better spend the night at her house.

Adrian Whitacre: She says, "There are many night faring spirits."

Alex Chambers: He ignores her, and continues on his way. But the next morning, he's found badly injured.

Adrian Whitacre: Something has torn up and bloodied his back and shoulders. In some places, he's been cut to the bone. He has been witch ridden.

Alex Chambers: He's been attacked by a nightmare.

Adrian Whitacre: A witch spirit, flying in spirit form, or an animal form. Katla then accuses Geirrid of being a [UNSURE OF WORD], a night rider or like a night attacking witch.

Alex Chambers: People believe her, and they bring Geirrid to court. But, Geirrid has connections, she brings witnesses. These are important people, and they convince the court that she is no night witch. She's fine, nothing to worry about. And things go back to the way they were. Katla and Geirrid's rivalry has quieted down.

Adrian Whitacre: But it's like simmering.

Alex Chambers: And then Katla's son, Otter starts to get into trouble. He gets on the wrong side of some powerful people, and Katla hears they're coming to arrest him.

Adrian Whitacre: Katla says to her son, "Okay, the men are coming. Sit here in front of me while I spin." And so, the men who are coming to arrest Otter come into Katla's house and they just see Katla, spinning wool with her distaff. So they leave. But then, when they get a little ways away from her house, they think to themselves, "Wait, was that the distaff? Is that what we actually saw? I think that was Otter." So they go back to the house again.

Adrian Whitacre: But this time, they just see Katla and a goat. And they go away again. And they get a little ways away, and they think, "No, I realize now, that goat was Otter." And they go back a third time. And all they see is Katla and a pig. And so they go away again, and the third time they decide, "No, we need a magic worker to fight a magic worker." So they go and get Geirrid.

Alex Chambers: On her way out the door, she grabs a sealskin bag.

Adrian Whitacre: As Geirrid walks in, immediately she goes straight to Katla, and she puts the sealskin bag over Katla's head to obscure her eyes so that she can't see and use that to do magic. And then they're able to capture and arrest Otter.

Alex Chambers: They find them both guilty. Katla and Otter. And the punishment is death. Katla and Otter are executed.

Adrian Whitacre: Otter is, I think, hanged, and Katla is stoned to death with the bag over her head.

Avi Forrest: The execution of a witch. Ugh, that's a lot of spirits and witches and murders. I think I need a break.

Avi Forrest: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Avi Forrest. I'm reading this strange book of dark tales I found in our recording studio. This next one looks pretty cool. It's called Secure, Contain, Protect. Back in the ancient year of 2008, the Foundation began its archive.

Avi Forrest: "Foundation Database: Department of Containment. Secure Facility Dossier. Site identification code: USINBL-Site-81. Referred to in the rest of document as Site-81. The first anomalous activity documented at Site-81 was SCP-2812 [RADIO INTERFERENCE] and several humanoid entities which[RADIO INTERFERENCE] jaws stretched open [RADIO INTERFERENCE] severe cerebral hemorrhaging. Site-81 contains living quarters and dormitories for over 1,000 personnel, a robust Keter-class containment wing, and several subterranean wings, over an area of 9.69 sq km. The public, however, is not privy to the function of Site-81. In fact, few in Indiana have any idea such a place exists. The approved cover story for the facility is not one of a state-of-the-art research base, but a Bloomington Municipal Water Treatment facility."

Ben Sisson: I think of these Sites as big jails for spooks and specters, right? The monsters and things that make you go crazy and whatever else, they take all these things, they put them in boxes, they put them underground. That's what a Site is.

Avi Forrest: Remember Hector from Hector Loves Water Treatment?

Hector Ortiz Sanchez: How I see myself is trying to be more knowledgeable. And that way, I will be one of the best.

Avi Forrest: We did a whole story about his work at the Bloomington Water Treatment plant. Sorry, I meant the SCP Foundation, Site-81. And you know what? It was disappointing. We had this whole episode about the water treatment plant, but I guess the universe doesn't want us to have nice things, because later on we find out it's a secret, scientific organization housing some of the deadliest known phenomena.

Ben Sisson: Yes, it's actually huge. You wouldn't know it just looking at it, but it goes all the way underneath Monroe. It's got eight or nine subterranean levels. It's crazy.

Avi Forrest: Our entire story is shot. And, listen, I don't care about how many dangerous artifacts this SCP Foundation has, I think we deserve some answers after they wrecked our coolest, most water treatment-themed episode. Thankfully, SCP author, Ben Sisson, has been very helpful in explaining why we're in this mess.

Ben Sisson: There exists in our world a secret paramilitary, pseudogovernmental society association, foundation, one might say, called the SCP Foundation.

Avi Forrest: Okay, so, we're going to explain some insane things really quickly. One: other dimensions, monsters, mind control. That's all real.

Ben Sisson: Different spooky monsters,you know, pretty standard fare, to haunted locations, to cursed artifacts.

Avi Forrest: And, two: it's not actually real.

Ben Sisson: I've written about, you know, buildings that hate you. And a lake, also near Bloomington, that is full of dead bodies, that might also not be dead, but, you know, create a compulsion effect that drives people into the lake.

Avi Forrest: The SCP Foundation is a massive online writing project produced by hundreds of different users. The stories primarily unfold in pieces called articles. And they're usually structured like government documents. But the format is always fluctuating, with new ways to tell stories.

Ben Sisson: I always tell people it's kind of a mix between the Men in Black and the X-Files.

Avi Forrest: The SCP Foundation has become an online cult classic with a devoted fan base, especially for the video game adaptations. To put this cult appeal into perspective, according to YouTube culture and trends, in 2019, global viewership of videos related to the SCP Foundation topped one billion views. SCPs have even influenced a major video game release. In 2019, the video game, Control, puts players into a strange and hostile laboratory with hallways of dangerous artifacts. By November of 2022, the game sold over three million units. Jeez.

Ben Sisson: This thing exists above and beyond governments. It simply exists so that the public can be protected and kept in the dark, literally and figuratively speaking.

Avi Forrest: Basically, it's a secret organization designed to safeguard horrors beyond human comprehension. It's even in the name, SCP: Special Containment Procedures. But also Secure, Contain, Protect. Plus, it's collaborative, meaning anyone with a good enough story can submit an entry and be immortalized as an SCP canon.

Ben Sisson: I am the site's number one overall rated author, I've been that for, I think, the last three or four years.

Avi Forrest: Ben has written dozens of articles under the name DJKaktus, and has been voted the site's top author, and that's no small feat considering the sea of submissions the site handles.

Ben Sisson: Really, what it comes down to is, you only need one good line. If you have one good line, you can do some stuff with that.

Avi Forrest: Ben wrote a story about Site-81, a branch of the super secret SCP Foundation, and he chose to set it in Indiana? Yes, you might wonder why. Why not New York or California?

Ben Sisson: I grew up in Plainfield, on the west side of Indianapolis, near the airport.

Avi Forrest: The Midwest is slowly being recognized as a great setting for spooks. Stranger Things, for example, is set in Indiana. But it's still a slow process and flyoverstates have always been fighting for relevance.

Ben Sisson: Even for somebody like me, who grew up in the most flyover of flyover states in a flyover town off the highway, that nobody recognized. People don't go to where I grew up. Even to me, those places have so much untapped potential for interesting stories.

Avi Forrest: So, yes, I was surprised that we had a SCP Foundation headquarters set in a Bloomington Water Treatment plant. And do you know what? It's a long story.

Avi Forrest: "SCP-2316 containment class: Keter. Warning: cognitohazard. Please repeat the following phrase slowly and clearly into your terminal microphone: "I do not recognize the bodies in the water." SCP-2316 manifests as a group of human corpses floating in a small group at the surface of the water. The identities of these corpses are [RADIO INTERFERENCE] though DNA testing has been inconclusive. Individual instances of SCP-2316 do not act on their own, but do seem to be able to act collectively as a single unit. The individual instances of SCP-2316 are unrecognizable, and you do not recognize the bodies in the water."

Ben Sisson: My grandparents owned, for the longest time, property in French Lake, Indiana, and their property line was 100 acres, but it backed up to a lake.

Avi Forrest: Ben was born in Indiana, and much of his work focuses on capturing the feeling of wild spaces and rural towns in the Midwest.

Ben Sisson: This article, Bodies in the Water, Field Trip is based on that lake, specifically where we camped out there a lot when we were just kids. And, you'd wake up in the morning and you'd go down to the lake to go fish or something, and there would just be fog. And every so often, you'd see things floating around in there. I was one of the older of several cousins and we would always jerk around the younger cousins and talk about how, 'oh, there's dead bodies out there, ooh, watch out.'

Avi Forrest: Growing up, Ben had plenty of adventures in the shadows of rural Indiana. Those experiences would inspire various tales for the SCP website.

Ben Sisson: A buddy of mine, him and his family lived kind of on the outside of town, and there was a rock quarry, more like a gravel quarry, near his house we called the gravel pit. And, a couple of times, you know, when we were kids, we'd go out there and mess around in this gravel pit, and it's just this big hole in the ground. All we were doing was going out there and blowing stuff up, and so it wasn't really much of anything. But, being in places like that, especially when it gets dark, and when there aren't other people around, it does have a kind of liminal quality to it where it doesn't feel like a place that people are supposed to be. Or, you know, doesn't feel like a place where you are alone even when you're very clearly by yourself.

Avi Forrest: The stories loosely track Ben's experiences growing up in Indiana, but they also show us a universal truth about writing fiction. It is really [RADIO INTERFERENCE] hard.

Ben Sisson: If you want to tell a story the way that a story wants to be told, it is very easy to fall into the cycles of self-doubt and criticism, and it can be difficult sometimes to have the confidence to expose yourself like that, especially if you're writing about your own experiences, or the experiences of people in the place where you are.

Avi Forrest: When I said the SCP project is collaborative, I meant that it relies on a collaborative editing process. If the story isn't successful enough, it can get taken down.

Ben Sisson: And I came from one of those towns where I was the good writer kid. But I hadn't really ever been challenged on that. When I started writing for the Wiki, I suddenly was having to not just meet a certain quality standard, or else have the work deleted. Which is one of the things I really like about the Wiki in that it has a self-policing deletions policy where if the community doesn't like something you've written, they'll just delete it. If a certain percentage of people download a thing as opposed to upload a thing, it just disappears forever.

Avi Forrest: According to the SCP website, in the decade and a half since it started, the number of articles written each year has quadrupled. It's hard to make a story stand out in all of that, even if users are just reading the new stuff.

Ben Sisson: Telling stories is hard, right?

Avi Forrest: For as much pressure this sort of model can exert, it does bring people together. For example, SCP-049.

Ben Sisson: I hated that article, the original version of it, I hated it so much. I thought it was just kitschy and dumb and super clowny.

Avi Forrest: The story was originally made by author, Gabriel Jade. But the SCP became more popular after it was rewritten, with the help of DJKaktus, or Ben.

Avi Forrest: "SCP-049 is a humanoid entity, roughly 1.9 m in height, which bears the appearance of a medieval plague doctor. SCP-049 will become hostile, with individuals seized as being affected by the pestilence, often having to be restrained should it encounter such. If left unchecked, SCP-049 will generally attempt to kill any such individual. SCP-049 is capable of causing all biological functions of an organism to cease through direct skin contact."

Ben Sisson: So, that article, SCP-049, it's very famous. I wrote an article called SCP-049J, which is a joke article, basically a parody of that article, called The Plague Fellow, and it was very much just like the Plague Doctor meme put into writing. And it did well. I still think it's maybe the funniest thing I've ever written. Gabriel Jade read that article and read a longer form criticism of 049 I'd put together. And he eventually came back to the site and asked me if I wanted to help him rewrite it.

Avi Forrest: This post-revision Plague Doctor has become arguably one of the most recognizable faces of SCP fiction. It's the result of dedicated collaboration and creativity. But the writers don't usually get recognized.

Ben Sisson: There's a gas station near my house I stop at sometimes on my way home, whenever I want to grab a drink, and one of the gas station attendants has a young son. And one time, when she and I were talking and I mentioned that I wrote for the website, she said, 'oh, my son loves that website' She goes,' he would love to meet you.' I said, 'well, have you read anything on the site? 'And he's like, 'I read 049', and I'm like, 'I wrote 049', and it was the coolest thing. I'd never had that moment, because there's nothing glamorous about writing for this website. It's not like being Stephen King.

Avi Forrest: But maybe it's not about recognition. These thousands of articles are written by usernames, not recognizable people.

Ben Sisson: And people generally don't know my real name. They know DJKaktus or Kaktus or that guy. They don't know Ben Sisson. That's me. You know, they don't attach those things together. So I don't walk down the street and people are like, 'oh, hey, you're that guy.' So, in the rare instances where you do have that kind of feedback, that is immensely gratifying. I can't imagine what it's like for people who experience that on a day-to-day basis. That's the kind of stuff that you would just get intoxicated on. Nobody should have that much power.

Avi Forrest: The goal of the SCP Foundation is to trick you. They want you to believe all of the anomalies, artifacts, and gods in their basement are real. But it's not mean-spirited, it's play. The SCP Foundation might be a covert organization with the heavy task of saving the world. But the fiction project, the one moored in our reality, is an opportunity to play like we're kids again.

Ben Sisson: When I was in elementary school, when I was six or seven years old, out behind our elementary school, we had a playground. And then behind that was a very thin woodline between the back of the school and the road. I mean, it couldn't have been more than 200 ft. And then there's another main road behind that. There's not a whole lot of interesting things that happen in a stretch of trees that thin, but there was one girl who I went to school with, who, to this day I cannot remember her name, but I know exactly what she looked like: she had red hair, she was, at the time to me, captivating, she had interesting ideas. And, she was one of those people who could look into a grove of trees that small and come up with fairy tales, in a way that I had never seen before in my life.

Ben Sisson: So, we sat out there, you know, it was a pretty simple playground, there wasn't that much to do. But on one of the trees in this very shallow woodline behind the playground, there was a board that had been nailed to one of those trees, like if you had put a ladder into the side of a tree and nailed boards into it. There was one board up high, and the board was just a board. The board had a single nail in it. Every so often the board would spin in the wind and it would go one way or the other. And this girl had convinced myself and half of our class that that board was put up there by a witch and it was cursed, and the turning of the board meant something or other. And, did it make any sense? Absolutely not. It was making stuff up. But we were kids and she said it in a compelling enough way that we were all hooked.

Avi Forrest: Maybe not everyone's a fan of incomprehensible nightmare treasures or psychic bodies in lakes, or plague doctors. But, even if it's just for a second, forget about the water treatment plant. Think about what's underneath that sprawling complex. What's swimming down in those concrete tunnels? What needs to be secured, contained, or protected? Next time you're walking by a lake, down a deserted road, think like you're seven again. Run through the grasses, have sword fights with tree branches. Look into that abandoned building and don't just see empty space. [RADIO INTERFERENCE] Imagine something is watching you back.

Avi Forrest: And the reporter finished her story and recorded it in her awesome, amazing, beautiful voice. The end.

Avi Forrest: That one was just okay. Anyway, how much time is left? Shoot, we need time. Let's take a break.

Avraham Forrest: Welcome back to Inner States. These episodes usually have a theme or a discussion. Alex is usually so good at these things. What would Alex do? I really wish he was here right now, but that does give me an idea. After working with him for a while, I think I can do a decent impression... Welcome to Inner States. Shows, talking, themes. Heck yes, I think I can do this. Let's land this plane.

Avraham Forrest: We usually have a guest. Whatever, let's just make someone up. Adrian Whitacre. Sounds good, sounds like a professor. A professor of literature, Adrian Whitacre. Alex would probably ask them something smart. Something like... What have you figured out about how people thought about bodily stability at that time? And what this shapeshifting reveals about that?

Adrian Whitacre: This is one of the things that I think is most interesting about the Old Norse sources in particular, is they give us this window into a very different way of understanding embodiment and the relationship between your body and the environment that you're in. There seems to be what other scholars have called a permeability between the self and the environment where, there's not a hard and fast physical boundary around yourself. In fact there's a lot of continuity between what is your body and what is the environment that you're moving through.

Alex Chambers: That makes me curious about how much control people had. This idea of the body with its hard boundaries, you're talking about how we tend to think of ourselves, our bodies now, in the 21st century. If you're more continuous with the environment, it also suggests to me on some level you have less control. It also seems that question of control seems tricky in some of these stories.

Adrian Whitacre: Yes. I think, like in Egil's Saga, the werewolf heredity that I talked about, stands as a symbol of not being in control. It's that chaotic element that makes Egil a chaotic person in the saga, difficult to be around sometimes. And it expresses that there are things that can't be controlled or contained in the same way. Although, I think there's a distinction to be made between, something that I described in Egil's Saga, where there's a hereditary chaotic element in this family, and what you see in Eyrbyggja Saga with Katla and Geirrid who are described as wise women who were crafty in terms of magic.

Alex Chambers: What you've just described to me seems to be a gender distinction. The witches and the women have control, and the men have less control. Does that play out?

Adrian Whitacre: Yes. I would definitely say that that is a true observation about these sagas.

Alex Chambers: This is making me think too about if the men are the ones who have less control over their violence and rage, on the one hand I feel that functions as a warning, potentially. Watch out for men. But at the same time it also functions as a justification, or excuse, like `Oh, these men who are committing this violence don't have control over themselves.' Is this just my 21st century sensibility, trying to put something on top of the 12th century?

Adrian Whitacre: I could see it that way and in addition, other scholars have talked about how magic for women can be a substitute for social power. So if you don't have access to different kinds of institutional power or authorized violence that the men, especially upper class men around you do, and if you can't access it vicariously, through a husband or a son, to enact that kind of violence or revenge for you, then magic can be that gendered outlet, that allows you to circumvent those institutions and take that power into your own hands. Which explains why that magic can be so frowned upon, and how women who use that magic are seen as threatening. Because they are threatening. Not just to that individual that they are taunting in the form of a seal, but also to the social order that says, no, power has to flow only through men.

Alex Chambers: So, how does thinking about werewolves and other shape shifters help us understand gender?

Adrian Whitacre: The werewolf forces us to think about, what does it mean when your inner self doesn't match your outside self? Or, when allegedly, your inner self doesn't match your outside self? When we see a creature who looks like a wolf, who howls like a wolf, who maybe attacks like a wolf, and yet inside that creature is trying to be something else, or knows itself to be something else. I think those questions are very applicable to ideas of gender. Particularly ideas of being trans and that sense of, when people see me, they see one thing, but on the inside I see something else. I think that the werewolf is sometimes, it's trying deliberately to make us think about those ideas of inside and outside, the relationship between our body and our soul. And sometimes I think it's incidentally helping us think about those things. Where it's producing this model that could help us think about gender, but could also help us think about lots of different aspects of ourselves.

Alex Chambers: And can you describe what you mean by gender? In the sense of, how does gender work as something that's both inside and outside? Internal and external?

Adrian Whitacre: You might say there are two main aspects of how we experience gender. There's the way that people interact with you, and that's informed by all of these symbols of the body that we read in a gendered way. So, you're going to speak differently, or move through space differently, in relationship to someone, depending on whether you perceive them as a man, as a woman, as masculine, or feminine. You're going to relate to them in a different way. We might call that the external, or perceived sense of gender. A sense of gender that you get from other people, and from the way that they interact with you, or from what they want from you. On the other hand we might say there's another aspect of gender. One that we often talk about as internal. You might say, people see me as a woman, but I don't feel that way. There's something in me that doesn't respond to those things, that doesn't feel that feminine things resonate with me.

Adrian Whitacre: That's not something that's coming necessarily from other people, but rather from an internal sense of who you are, and we might call that the internal aspect of identity. These two things are always in tension with each other. I don't think either of those things, 100 percent determines what your gender is. It's always this kind of push and pull. That's, I think, where the metaphor of the werewolf can help us think about that, because, the thing that's fascinating about the werewolf is that it's both at the same time.

Alex Chambers: Okay, cool. One concern that I'm feeling about using the werewolf to think about gender and especially if there's a link with transness, is that the werewolf is monstrous.

Adrian Whitacre: I definitely see where there can be a concern with, do we want our images of queerness or images of transness to be monstrous? To that I would say, they always have been. Images of monstrosity have always been used in a variety of ways, not just werewolves, to represent that. I think there's obviously a negative aspect to that. There's an idea that queerness is threatening, that it's dangerous, but I think also there's something in there that is about how it's disruptive. It's something that is, in fact, breaking social norms, and that that can be a good thing. That can be a redemptive thing, to smash those. Many other people have said that there's an identification with the monster that they can become a positive, cool thing. Werewolves are cool, and they represent how you can become something other, and that can be powerful as well. You can say that that power is threatening, or evil, or dark in some way, but it can also be something that is empowering in a positive sense.

Avraham Forrest: Adrian Whitacre is an Assistant Professor of Literature at Eureka College. They wrote their dissertation on Medieval Werewolves.

Avraham Forrest: You've been listening to Inner States, from WFIU in scenic Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us, or if you've got some sound we should hear, let us know, at WFIU.org/innerstates. If you like the show, review and rate us on Apple or Spotify. What's even better, is sharing the show with a friend. This episode of Inner States was produced and edited by me, Avi Forrest, with support from Alex Chambers, Eoban Binder, Jillian Blackburn, Mark Chilla, LuAnn Johnson, Sam Schemenauer, Jay Upshaw, Payton Whaley and Kayte Young. Our cool as heck Executive Producer is Eric Bolstridge. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Special thanks this week to Adrian Whitacre, Reilly Donaldson and Ben Sisson, my own personal Stephen King. Time for some found sound.

Avraham Forrest: That was Crows in Bloomington, 2024 edition, recorded by Amy Pickard. Until next week, I am the wonderful Avi Forrest.