Todd Burkhardt: What's really cool about needle felting is you are puncturing the wool into the felt and the needle goes through that piece of felt into the backstop, which is also material, and it pops. Honestly, I've given IVs before as a combat lifesaver in the military and so it's very similar to puncturing skin. Right, it has this pff like of release and it's very therapeutic.

Alex Chambers: Needle felting is therapeutic. Maybe that's not news. But convincing veterans in Royal Indiana that they might want to take up needle felting, that's another story. And that's the one we're talking about this week. It's Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers. Coming up a conversation with Todd Burkhardt about what happens when veterans start making masks in needle felting. A life in the military and making art afterward on this week's Inner States. Coming up right after this.

Alex Chambers: Welcome to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. I'm Alex Chambers.

Alex Chambers: Up until a few years ago, Todd had spent his whole working life in the military. 28 years. His last military job was running the ROTC program on the Indiana University campus. When he retired from that and moved to civilian life and a civilian job also on campus you'd think it wouldn't have been that big a change but he felt it.

Todd Burkhardt: I was in charge of things. I was running things. And, you know, doing real world things and then I'm some staff weenie like, you know, putting together meetings to talk about some things, what's your definition of "is" is.

Alex Chambers: This new job, this staff weenie job, he does like it. He works at the university's Center for Rural Engagement where, along with running meetings about the definition of "is" he helps bring the university's resources to rural parts of the state. He also teaches the law of war in the criminal justice department. And because he's a military man, he was particularly interested in the challenges veterans face. We'll get to what he's doing to help but I want to start with Todd's own experience. Growing up, I don't think he imagined he'd be trying to convince veterans to sit down and start needle felting with him.

Todd Burkhardt: I grew up in a steel town known as Bethlehem. Billy Joel, back in the day, sung about Allentown. Well, Allentown, Bethlehem - I guess Bethlehem, harder to find words that rhyme than Allentown but it was a story about the steel mill going under or going bankrupt and so that's my hometown. I grew up in a steel town, center city. My dad was a house painter. My dad never went to high school. Became a house painter at the age of 13 and worked for his father until my dad passed away about 20 years ago. And I think, some time after the end of high school, I recognized that I don't know if I really saw a future for me in my hometown, I had great, loving parents, I had a lot of great friends, I enjoyed my time in high school, but, I needed to get away from my hometown.

Todd Burkhardt: And so I did a year at college, I played college football. Prices were really expensive. My parents couldn't help with paying for tuition and I became, I guess, disillusioned and I just needed to escape, and so I went down to our army recruiter, signed the line and it was called the late entry so I signed paperwork and then five months later I would leave for the service. And I remember that night after I signed, I sat at the dinner table and my dad came in late, as always - he was out working - and somewhere between "Hey, can you pass the mashed potatoes?" I told my parents I enlisted in the army and I broke my mom's heart, 'cause I was the first generation college student ever in her family to go to higher ed, and I guess her dreams and hopes were kind of shattered there. And then my dad, he thought it was great. And I think in some ways I escaped and he never did.

Alex Chambers: His grandfather served in World War Two but Todd says he didn't really come from a military family.

Todd Burkhardt: I guess, you know, the commercials of "be all you can be", which was the mantra and the motto back in the day, spoke to me. The physicality, the team-building and sense of adventure, of getting out of where I was. And I think I was really just enthralled with that whole type of lifestyle and opportunity and adventure.

Alex Chambers: And although it broke his mother's heart at first, she agreed later on that it was the best decision he could have made.

Todd Burkhardt: Because I think, in a lot of ways, the military is an equalizer. It enables people to get out of a position that they might be in or might not have access to certain things and so it provides opportunities.

Alex Chambers: Todd took advantage of those opportunities, but right after he enlisted it didn't exactly feel like opportunity.

Todd Burkhardt: I enlisted in the army December 27th, 1988, which was a bad time of year, I have to say. Two days after Christmas I enlisted in the army. I'll never forget my first New Year's in the army. I was in the army about - what is that? - six days or four days and, you know, lights out at 9PM and everybody in the barracks, you know, crying because we're away from home. Yeah, it was not a good time. [LAUGHS].

Todd Burkhardt: We flew out of Pennsylvania down to Louisville and I did my basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Arrived at like, I don't know, one in the morning or something. It was rainy, it was December. And so we landed in Louisville then there was a charter bus that took us to Fort Knox. It was really calm. Nothing really going on. I expected like the movies, people screaming and carrying on, but it was really chill. This was also one in the morning. And so we got off the bus and they took us to the mess hall to get something to eat, which was great. So I ate some old burgers or whatever it was. Went to sleep and then, at, I think it was 5AM, the drill sergeant came in and threw big trash cans, screamed, "Carry on!" I mean, you could see the whites of everybody's 'cause we were like what did we get into, right? And so this is that moment where you're like, oh my god, did I make a mistake?

Alex Chambers: My main experience is just seeing the movies, you know?

Todd Burkhardt: I think a lot of them are accurate. A lot of cursing. I think there's a lot less cursing now, but a lot of cursing. You know, doing different exercises to muscle failure, and I'll never forget when we were in, it was called like a reception station where you get there, you get your uniforms, you get all your shots, you do your will and your life insurance and all that type of paperwork, and you do another medical physical and review board and stuff like that and you do all this stuff so you are finally ready to do training. So, during that phase, the drill sergeants might yell occasionally or throw a trash can to wake you up or something like that but for the most part they leave you alone. So, it was six or seven days or something like that. And then we finished all that and then the real drill sergeants came over to get you to bring you to the barracks where they were gonna train you for the next 16 weeks. That was a significant emotion event.

Todd Burkhardt: I just remember drill sergeants around us screaming, carrying on. Don't know what to say and any answer you say is incorrect, whether you say yes or no or whatever and the questions, the way they were worded, you were completely confused. And also you had people in your face yelling and carrying on and screaming at you and you're scared to death. You're away from home. And I just remember we're on the bus, and we have two big duffel bags and also like a rucksack or a backpack full of gear that we were assigned, and they were screaming for us to get off the bus and run to the barracks which, I mean, maybe it was, I don't know, half a football field. It wasn't too long. It seemed like the longest mile. It seemed forever 'cause I was carrying all this gear and the drill sergeants were lined up and they were screaming and yelling and gear was falling and people were tripping. It was something. It was significant. I mean, to the point where, you know, 35 years later I remember it vividly.

Alex Chambers: Todd says it's not an accident that basic training starts off that way.

Todd Burkhardt: I guess the thought process is really to break everybody down, right? That there's no individuality, it's team, and wherever you came from, we don't care. We're going to instill in you professional military ethic and value system that a professional soldier should have.

Alex Chambers: Is it explicit, though? Do the sergeants reflect to the new soldiers on why they're treating them that way? Not so much.

Todd Burkhardt: That feeling of did I make a mistake, it went on for probably the next six weeks, [LAUGHS] you know? So it went on for a long period of time of like, oh my god, what did I get myself into?

Todd Burkhardt: I think there's a moment where you have to search for yourself and kind of question is this what I want to do. And there were guys, had a couple of guys that once the drill sergeants bang on the door and they wanted to home and a lot of the drill sergeants say, "Go sit the F down, you're not." And I think that was great because some of those guys, they stayed in the army and they were great soldiers. And there were other guys that, I guess, drill sergeants probably did that for everybody but then got to see maybe when a guy came back or maybe the way he was acting in a couple of days, they knew that this was not gonna work and they processed him to leave the military.

Todd Burkhardt: In some ways I joke and say it's a love hate relationship. There's plenty of things in the army that I had to do that wasn't a fan. Sleep outside when it's really cold or train in the mud or stay up all night over a couple of nights or traverse six miles in the woods. You know, whatever. So, there's a lot of times where I'm like oh my gosh. What am I doing? But inevitably there was always much more good. The opportunity to work with great people, do amazing things, build teams, accomplish things and just opportunities, like I mentioned, about to going to grad school and teaching future leaders of the United States Army. And so, when put in perspective, being cold or a lack of food or a lack of sleep in short durations wasn't that bad, you know? I mean, some of it sucked but I mean it wasn't overall. You know, I think in a lot of ways, as I mentioned, I think I benefited from the army in so many ways.

Alex Chambers: He got a Masters and a PhD, he taught at West Point, wrote a book on just war and human rights, but eventually it was time to move on.

Todd Burkhardt: My first year here leaving the military, it was hard for me in a lot of ways because, as I mentioned, I'd spent 28 years in the military, active duty, and so I was used to a certain type of operational tempo or momentum. I was used to a way of a team operating. I knew my task and purpose and how I fit into the larger picture and so when I left the military, for good or bad, I'm ultimately tied to I was an officer in the United States Army. That's who I was. And I was an RTC here and I said we just won a big award, and my self identity was captured by my military service, for good or bad. And so when I left the service, of course, you operate in teams but it's not the same. Deadlines are not necessarily the same the way they are in the army. When you tell people to do things, they do, and you also have the right to dictate or direct people to do things in the military where it's more nuanced.

Todd Burkhardt: And so all of that, right, and finding out how do I fit in as a staff person in a center who's doing great work, and I was really interested in being a part of that, but I felt disconnected. I spoke different, you know, in acronyms and military ease and jargon and people are like--

Alex Chambers: Like what?

Todd Burkhardt: Like ASAP. So, "Hey I need that ASAP." Right, maybe that's an easy one, and it's always interesting because civilians don't say "ASAP", they say "as soon as possible." And it's funny because when a civilian says that, that means, hey, as soon as possible, I need that sheet. In the army, it means, get it to me effing now. And so it doesn't mean as soon as possible, it means you're already late getting it to me and as soon as possible, it's said too slow, so we say "ASAP" because it means really fast, I need it now.

Alex Chambers: It means yesterday?

Todd Burkhardt: It means yesterday, right? So, just that, as a silly one. I use a lot of analogies and they're all war-like and I'm like oh my gosh, you know, because it's just funny, but that's how I speak. And so, I felt in some ways, of course I have an academic background, I just didn't fit, in a lot of ways. And sometimes I feel like telling where I'm from or my stories, I feel sort of like a gorilla, you know, kind of beating my chest or something and people are like what is that? It's like I just don't fit in. And I feel my self-identity and sense of purpose had been gone. I had this, they were concrete, they were palpable in the military, and then, what I had been doing for three decades is now no more. And just trying to, you know, this resurrection, so to speak, of like how do I make the new Todd or the next new phase of my life, what does that look like? And it was hard for me.

Alex Chambers: I mean, in order to have a resurrection, you have to have a death. And so you were like dealing with having lost a pretty major part of who you were.

Todd Burkhardt: Yeah, absolutely, right? And I accomplished a whole lot, I think I was pretty successful in the military. And so, this new life, it was hard. I work with a lot of great staff in faculty and they're wonderful people, I don't mean that in any way, they're caring and that but I didn't feel connected and I didn't know how I fit. And so, I think, you know, I felt isolated. I felt, in some ways, not through anything people here at work did but I did feel marginalized and I was depressed. I was depressed.

Alex Chambers: He'd been in charge of things, making things happen, and now he was running a lot of meetings. It didn't feel like making things happen. Then he got an invitation that sent him in a direction he couldn't have predicted. If you've been listening, you probably can, but we're gonna take a little break before confirming that. We'll be right back.

Alex Chambers: It's Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers and we're talking with Todd Burkhardt about his life in the military, how hard it can be to talk about, and what can help open things up. Todd had been working at a center on the IU campus. Things were feeling a bit meaningless. Then, one day, an art therapist at the Eskenazi Museum of Art, the campus art museum, invited Todd and all his colleagues to an open studio event. "Come on over", she said, "I'll take you through some art-based activities that help with stress. It'll be fun." So they went. She'd laid out a bunch of materials. There were various prompts for drawing and even some group activities. Todd was surprised at his reaction to the whole thing.

Todd Burkhardt: I am not artistic and I have not done art since high school, and the only reason I did art in high school is, well, it was graded and you needed it to graduate. And I have to tell you, pun intended, I was drawn to this, right? That this intentionality of expression through non-verbal means, I really liked. I liked the ability to express. I come from a profession in some ways that is stoic in that you suck it up and you drive on. You better get comfortable with being uncomfortable 'cause that's the way it is. And I understand that mantra, but, the problem is when that mantra permeates every aspect of military life, that's problematic because you don't ask for help, mental health, if you have issues it's seen as a weakness. The military's getting a little bit better now but still have a long way to go and so what do people do? Well, we drink.

Todd Burkhardt: It's amazing how much alcohol the military sells. Best way of coping, I guess. And so using art, I thoroughly enjoyed those two hours, and I could just express in such a way where I didn't have to say anything. You could just see it in the page. And afterwards, I said to Lauren, the art therapist, I was like, "You know, I think there's something there that this helps, right? It's another tool that you can put in your toolkit or your tool bag that can help regarding mental health or about expression. And I said maybe if this can help me, there's a lot of other veterans right outside that are just like me or worse than me or not as bad as me that maybe might take to this. And so we were like screw it, let's just start doing stuff. And so we start reaching out to local veterans who were connected in the community or non-profit and we start hosting and facilitating, we've done some art therapy but generally we've done art-based wellness events. And so we've traveled to about 12 or 13 different counties in Indiana and put on events that last anywhere from 90 minutes to two and a half hours using art-based wellness, whether that's needle felting or [UNSURE OF WORD] or mask-making as a way for veterans to express themselves through non-verbal means.

Todd Burkhardt: We get a lot of feedback and veterans seem to really like the opportunity to express but also there's a connectedness of pulling veterans in into a room that, to me from my experience working with different groups of veterans around the state, there's this common narrative. Although maybe we don't know each other prior to this event and you served in the Vietnam War and I served in the Cold War and you're a man and I'm a woman or whatever the case may be, it doesn't matter, you served three years or 30 years, you're a veteran so you have gone through some of the significant emotional things that I had to go through and there's this, kind of, the facades disappear a little bit and there's, for the most part, there's a sense of trust and I think it's just really neat to see conversations unfold, whatever those are. If they're war stories or they're talking about what they're doing now, whether they're talking about their grandkids or their kids or they love to go fishing. It doesn't matter. I think conversation's immaterial but it gives the veterans a chance just to talk to somebody who's like them and I think that's something that I never thought when we start putting this together and I think that's just a great component of that.

Alex Chambers: The conversations that you're seeing between the vets, are they different than they would be without the art aspect?

Todd Burkhardt: It depends. So when we do these events, we let the vets go wherever they want to go in conversation. So, we've had conversations, I talked to a woman veteran during the Indiana Department of Veterans' Affairs Women Wellness Retreat. We had about 50 women veterans who were part of the Brown County state park last March. They range from early 30s to late 60s and it was just wonderful. I do all the art making with people as well 'cause I'm a veteran and I want to go through it, then also I can give feedback of how maybe we can do things better as well and I want to engage, right? And it's just interesting. I had a really nice conversation with a woman who is now a truck driver. She served in the marines and it was a really nice conversation about her job and where she drives and she does cross-country deliveries and stuff like that. But then I've been in other ones where I had people who wanted to talk to me about the death and dying that they've been exposed to.

Todd Burkhardt: So, I think it just depends of what people want to talk about. I think, in some ways, people, they want to share stories but they need to do that in a way that they comfortable and so I feel in some ways privileged where people have wanted to talk to me about some of things that they've witnessed or suffered or been exposed to to maybe get it off their chest or share. And it's interesting 'cause I've worked with veteran service officers as well and so a veteran service officer, there's one for every county in the state. In multiple counties, we've done different events. And this one veteran service officer whose whole role is helping veterans with benefits and entitlements and we sat on the one side during this event and he went into a lot of depth about a lot of tragic things that happened to his unit in Afghanistan. We didn't have to go there but that's where the conversation went. Where he wanted to take it.

Todd Burkhardt: And this one veteran service officer, whose whole role is helping veterans with benefits and entitlements, and we sat on the one side during this event and he went into a lot of depth about a lot of tragic things that happened to his unit in Afghanistan, and we didn't have to go there but that's where the conversation went. Where he wanted to take it. I never pry, I ask questions. What he does for a living is he helps veterans. But I don't think maybe, at the end of the day, anybody asked him about him. And so, yeah, I think it was a way for him to share his stories.

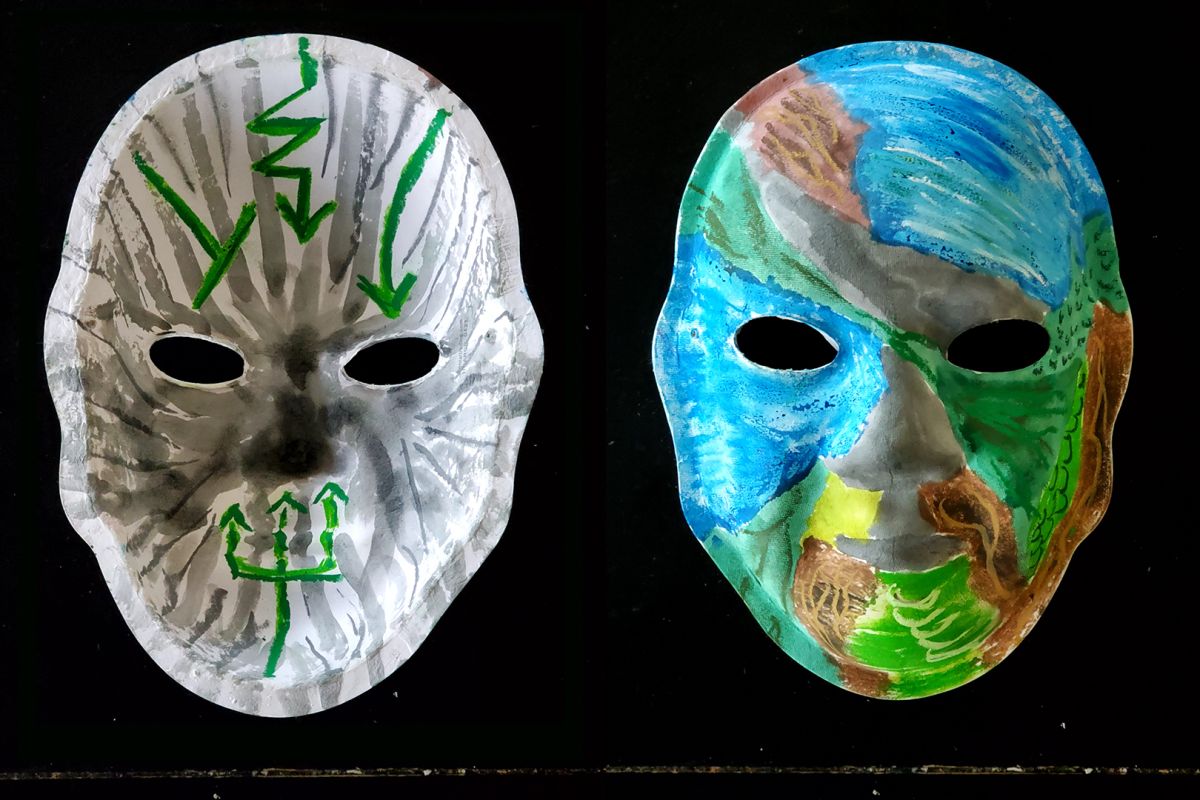

Todd Burkhardt: And so, I mean, I think it just depends. And I think one of the neat exercises we do is we make masks, and so do exterior and interior of the masks. These are always amazing and it's amazing just to find some of these people who are very artistic and I'm like oh here's mine, it's not too artistic. But what's really neat about it too is having the opportunity on the back end, if they want, and we've had plenty of veterans that don't want to explain what's on the inside of the mask. Don't have to. We don't want anybody to talk that they don't feel comfortable. But it's interesting to hear a lot of stories regarding what's on the mask, especially the inside, and so it depends on how you frame the prompt but it could be: what do you show the exterior world or what do you show to the world? And then the inside, maybe: what do you hold close? Doesn't have to be negative, it can be positive, but what do you hold?

Todd Burkhardt: And so that conversation can get really deep. It can get really sad. I've had multiple veterans talk about losing soldiers. Just did one in Brown County not that long ago. A senior citizen who served a long time in the military, had been in multiple wars, multiple combat deployments, and after he lost soldiers in the first deployment through combat he said he would never lose soldiers again and he did. And he promised family and friends that he would bring his whole team home and he didn't. Yeah.

Todd Burkhardt: So, you hear those stories and I feel maybe, in some ways, we're an outlet, because I don't know to hold stuff in, and I'm guilty of that too, but sometimes it's good to be able to share it among a group of people who maybe experienced similar things. Or they definitely have an understanding, because the military, although it's a large organization, anybody who's spent any time in the military has friends or colleagues that are dead now, either through combat or training accidents or invisible wounds. Suicide and others.

Todd Burkhardt: And so, I think it's those commonalities and, you know, as a soldier, fundamentally we train, I mean, we train to kill. And so, at the end of the day, my profession's about taking enemy combatant lives and being effective and efficient at it. And so, everything's focused and surrounds itself around death. And so if you're not a person who's training how to neutralize targets, you are somebody who helps support that war fighting function, and so everybody in the military is pretty aware and conscious of just the death aspect. And a lot of the training that we do as well, it comes with risk. And I just think that these events we put on, hopefully in some ways, provide opportunities for veterans just to kind of express themselves with some of these things that they think about that will stay with them till their end of days. Yeah.

Alex Chambers: How do you deal with that?

Todd Burkhardt: [LAUGHS].

Todd Burkhardt: It's interesting you say that, because some of these are nice, they're easy-breezy, man. And so we talk about, "Hey, I'm a truck driver and I drive cross country and I have a dog and the dog is with me in the cab." Those are great. But when we get into some of these other ones, I do feel it.

Todd Burkhardt: I guess in some ways, I don't want to say "share their pain" because I have no idea what that pain is from their personal stories, but it does affect me. I mean, you can just tell in my voice. I mean, when you just start hearing some of these stories and they're terrible or tragic. But I think, in some ways, it's an opportunity for veterans to express because, in one way or another, they don't have access to care or don't know how to get into the A care or maybe they don't qualify for a certain type of care or don't think they qualify for it or not or are not interested in it. And so I do think that these events, in some ways, hopefully provide, not maybe necessarily closure but maybe some post-traumatic growth. Because I think from my own personal journey, talking about some of the things that I've experienced has helped me in some ways. And so, in some ways, I think it does with them as well.

Alex Chambers: I guess I kind of want to come back to that question I just asked though. The thing that you said about the fact that fundamentally you're being trained to kill people or support that. How do you deal with that? Does that make sense?

Alex Chambers: How do you live with that on some level, as a person? Like, not just how do you understand it theoretically and just war and all your academic writing .But just like as a person. And I think it's like, for you like as an emotionally mature person now, but it's a really heavy thing to carry.

Todd Burkhardt: Yeah. I mean, that's a very heavy question, as a matter of fact. I think it's a great question. I think a lot of maybe it comes in with just repetition in training, right? Be very exposed to all kinds of things in the military for training. Loud noises and explosions and working together as a team and shooting your rifle all the time and carrying your rifle and using certain tactics. So, a lot of things become second nature. Pointing guns at people, right? We do a lot of war games where there's blanks or laser tag or some type of simulators, and so it's always about killing the other team. Of course, unless they surrender. So, I think that's just ingrained into you where a lot of that becomes second nature. And I think the training and the more realistic hard training, the better probably prepared you are to do it in the real world.

Todd Burkhardt: And, I have to say, it's interesting, chaplain's a pretty interesting profession in the military where all chaplains, I've seen them of course give sermons and church services and stuff, but they are all really good in talking about to soldiers that might question their obligation to killing on behalf of the United States.

Todd Burkhardt: That's one thing I guess all chaplains learn through the military, that they can talk, in depth, reasonably, rationally, about why it's okay to take another person's life. Meaning an enemy combatant .and it's just interesting 'cause I never realized that about chaplain's but I guess that's probably one of the biggest things that maybe people go talk to chaplains about. And so, they're very well versed in talking to somebody about the justifications of why it's okay to pull a trigger on an enemy combatant.

Todd Burkhardt: And so I think just the training for such long periods of time and shooting and practicing and, working as a team, you know, that was my daily job, and so I think you just become - I don't want to say desensitized 'cause that's, that's not the right word, but you understand that's what you do when you become really good at it. You become effective at it and efficient at it.

Alex Chambers: Todd strikes me as the kind of person who's effective at whatever he takes on. But when your job is taking enemy combatant lives, as he put it, and losing people you work with or who you've sent into battle, it's a lot to carry. There's a reason Todd connects with the veterans at these workshops.

Todd Burkhardt: I was in a unit which was special operations joint task force, and I was part of a commando SOAG, special operations advisory group. Served in Afghanistan 2013-14. And we had three of our soldiers, one US Air Force and two Slovakian Special Forces, that were killed with an IED. Improvised explosive device. And it was a vehicle that had the explosive device attached to it and the vehicle came back up behind one of our vehicles and detonated, and it killed all three men in the first vehicle. The guys in the second vehicle survived. I was in Afghanistan, and you do whatever job that you're assigned daily,and we know the hazards involved in being in a war-torn country, but I don't think anybody is ever ready for something like that. And it struck our unit.

Todd Burkhardt: It was December 27th when it happened and they were killed instantly and it's emotional in a lot of ways. One, I mean, lost our brothers that we're close to. Young, late 20s, all three of them. Two were married, one with kids, one single. And that's it. So, that was hard. I mean, it was incredibly hard to kind of move through that, you know, and we have a ceremony there to honor them. But what's interesting too when something like that happens, all communications to the outside, they go black so they're shut down. So, our WIFI, our internet to the outside world, unclassified. There's no communication inside or out. And so because, and I understand this, the army needs to notify the next of kin that their family members had been killed. So, that's incredibly important 'cause you sure as heck don't want to put something on a Facebook, right? So, it completely makes sense.

Todd Burkhardt: However, what's hard about that, as well as losing your compatriots, you know, your friends, something like that, but also I can't contact my wife to tell her it wasn't me. So, there's a void in communication for about three days, so there's no access to the outside, and so my wife, just like any other spouse, would be following the news, actually she watched a lot of Al Jazeera on her phone because they covered more of Afghanistan than the United States. A lot of times it was just a blip on the bottom of the screen. I flew a lot in helicopters and when a helicopter would go down or there was a car bomb, she was always worried, especially if she thought I was out somewhere 'cause I traveled a lot, all over the country, as a matter of fact, just based on what job I had.

Todd Burkhardt: So, that was really hard with not telling my family that I'm okay. It's somebody else in our unit but I made it, you know? And so I don't know what it's like being on the home front, and I think that's incredibly hard for a family unit to try to negotiate that. But then, it's interesting, so the three days are over and I get hold of my family, but it's also we got a job to do and so things didn't stop. We had ceremony for the three service members, two of them, one on our small base camp and then we had a bigger one as the bodies with the flags on it in caskets were loaded onto a C-17 plane and flown off to Germany, and then Slovakia, and the United States. But then it's like okay, let's go. Next mission, right? And so life didn't stop, missions don't stop, enemy's still out there and we still need to continue what we're doing.

Todd Burkhardt: And so, just the whole op tempo and then trying to even deal with those stressors and probably the biggest thing I had for mental wellbeing in my deployment was the gym. Throw around some weight, some steel. We have a gun range too, so we would shoot a lot. But I think it's just the way you need outlets and I think physicality or being physical is one of those. So, I think that was incredibly helpful. It's interesting, I think some of the things that I experienced in the military or during deployments, they don't really manifest until much longer after that. I'm busy, I'm trying to figure out ways to defeat Al-Qaeda, Haqqani and the Taliban and so that's what I'm gonna do. I want to defeat, destroy, neutralize, dismantle those organizations as best I could. Well, we lost that war, but anyway, that's what I was trying to do.

Todd Burkhardt: Then later, maybe that's weeks later, months later, years later, where you're no longer in that, that it really maybe wears on you, or maybe there's things that you could have done differently that could've somehow protected people who lost their lives, that never really thought about until after the fact.

Alex Chambers: It sounds to me like one of the things that this creative arts program creates is a space for people to hold each other's experiences.

Todd Burkhardt: I've heard some really sad stories, tragic stories but, to me, there's this that people want to say, I don't ask, I mean, I don't, I don't ask, because I don't want to make anybody feel uncomfortable but it's amazing how many different stories I heard and they're all tragic on one level or another of what somebody experienced or suffered or went through. They live with that, and I think if given an opportunity and a safe environment, and a safe environment of people that they feel there has to be a certain level of trust. We all have kind of been through the military together. One aspect another, three years, 30 years, whatever. That they feel comfortable enough where they share that and everybody in there can understand that.

Todd Burkhardt: I think that's important and I never really thought about it when were starting putting this together, of that connectedness and wanting to share as much as just actually using art to express. But then the opportunity of wanting to them explain what your art is and what does it mean.

Alex Chambers: The masks, in particular, lead to a lot of discussion. The idea is that on the front of the mask you put what you show to the world. On the back of the mask, it's what you keep inside.

Todd Burkhardt: And I've had veterans that were like, "Nah, I don't want to talk about it." And whatever it is on the inside, or they don't even want to show whatever it is on the inside, but you know they worked on the inside 'cause you saw them on the other side of the table cranking it out. Hey, that's cool, and they take it with them and whatever they do with it, you know, but they were able to, in some way, maybe get some aggression out. Get some feelings out. Put something into it and maybe, in some way, you know, it helped.

Todd Burkhardt: I think with art-based wellness, I don't think it's the end-all be-all but I think it's just one thing that people can use towards improving wellbeing and having an outlet. Getting good sleep, have a social connection, exercising, having a hobby that you like. All those different things are so important to mental wellbeing and health. This is just one more.

Todd Burkhardt: One of the things that I learned from doing these events, a lot of veterans after the fact are like, "This is awesome. When you coming back?" And it's always interesting 'cause I'm like, okay, when do you guys want me to come back? And then I also have a day job and trying to figure out all these others things. And so, we do go back but maybe it's four months from now, and what I recognize with that is that's not gonna work. If there is something that you can use that can maybe help you, you have to be more involved with it than once a quarter. And so, with that was really, after talking to multiple veterans, I thought I wonder if somehow we can package this up where they could take it with them. And so that was really my thought and impetus behind The CAV Book.

Alex Chambers: The CAV Book. CAV is "creative arts for vets" and the book, Todd developed it with a team of art therapists and social workers. It's a step-by-step therapeutic guidebook for veterans with veterans resources and stories from veterans. It also comes with an art kit: charcoal pencils, watercolor pencils, oil pastels.

Todd Burkhardt: We will mail it to any veteran, the spouse of a veteran or anybody currently serving in the military anywhere in the United States, or at an APO address if they're stationed over in the Middle East or in Europe, or whatever the case may be. And you can be in an homeless shelter or incarcerated and we send it to veterans there as well. And this is a great way where I think it increases access 'cause you don't have to come to my event. We'd love if you'd come to my event but you don't have to, you can do this in the safety and security at your kitchen table or on your La-Z-boy or, you know, while you're deployed, somewhere in your barracks at night or in a homeless shelter. And hopefully, in some ways, there's a lot of art exercises and journaling in it where maybe it can provide that outlet of intentionality and expression through non-verbal means. And that was really the beginning of this whole project two and a half years ago that it really has helped me and it continues to help me.

Alex Chambers: Okay, we're gonna take a quick break. When we come back we'll talk about why I was a little skeptical about the book at first. Stick around.

Alex Chambers: Inner States. Alex Chambers. We're talking with Todd Burkhardt about creative arts for vets, a program he started. He worked with a team, an art therapist, social worker and more to develop a book so veterans could use art for wellness on their own. I got to admit, I was skeptical about it in certain ways. I know not all vets are men but, still, the majority are and whether you're coloring or working with felts, it's, you know, not very masculine.

Todd Burkhardt: I'm glad you brought that up. Okay, so, you're absolutely right. So, for those that can't see me, I'm kind of built like an ogre, right? Bald, hopefully I have some muscles, right? And I think the issue is, any time I say, "Hey, we're gonna color for mental health" a lot of guys, because it's macho, are like, "I am manly and I don't color." Well you're missing out. What I try to say, "Look at me. I look fairly manly, I've done manly things. I was in the infantry, right? I was infantry officer which is pretty hardcore branch in the army and so I color. And so if I do it, I think maybe you could do it as well."

Todd Burkhardt: We're doing two things that I think, for the most part, a lot of people in the military are uncomfortable with, especially men. We're doing art, which can be seen as feminine, and also we might talk about mental health, not that we say anything on the flier but it does come up 'cause we're talking about mental wellbeing. And so, I think for those two things, especially as I talked about earlier, being inculcated in such a way where, you know, suck it up and drive on and, oh, you can't handle something, you're weak mentality, well, the last thing a lot of people who were in the army want to do is go to something about mental health because their whole time in the army - I say army 'cause that was my background - in the military is to shy away from mental health help, right? And so, twofold, two reasons why not to come to this event: one, we're gonna color, and two, it's about mental wellbeing. Oh my gosh, give me a break.

Todd Burkhardt: So, I think there are some people that we had RSVP and then they don't show up, which is sad. So, we really like that you can bring a partner or a friend 'cause we think if you do that you'll actually show up.

Alex Chambers: Todd says it can be tricky to get people to come and to get involved.

Todd Burkhardt: I talk about my background and, as you saw in the interview, I'm kind of emotional with some things and it just kind of happens. And I don't mind, right? And I admit that I do have issues, because it's okay, and I'm working through them and, you know, maybe somebody hears this, they're like it's okay to mention that, yeah, maybe this isn't a bad thing to pick up using arts or find my other niche of woodworking or whatever the case may be that can help me with mental wellbeing.

Todd Burkhardt: It is interesting because we had some reluctance in some groups and it's weird. As you know, being a professor, when you have a class, every class has its own dynamic, right? And so it's like high energy, low energy, right? Reluctance, it's happy-go-lucky. Whatever it is. And so, that's the way these groups are. And so you never know. And we've had a lot of women which is probably just indicative of it being arts, we've had a lot of women veterans which is great because women veterans, even more than male veterans, are more marginalized and I can talk about that down the road sometime. But, as you can probably imagine, for a lot of reasons.

Todd Burkhardt: So, it's wonderful to have women be a part of it and they jump right in and they're just like, "This is awesome". And we did textile, mixed media, designing too. It was like Joann Fabrics on steroids. We did this one event, oh women loved it. I did it too, it was cool, but it was like buttons and fabric and sequins and it was amazing. But the women loved it, and it was one of those women veteran wellness retreats. So it wasn't a guy thing 'cause it probably would have had a lot of men just walk out. So, we think masks is sort of gender neutral or non-binary, and so it's something anybody can do. So, we tried to find something that it doesn't matter who you are. And even the needle felting, at first, I have to say, it sounds very feminine but when you put a needle in your hand and you're jabbing, forcing it into material, there's something about that methodology, that rhythm, that is incredibly, I think, relaxing and it doesn't matter who you are. I mean, you're holding a metal spike, right, so hopefully there's some masculinity in that.

Todd Burkhardt: We've had some where we say, "Okay, this is the prompt and this is what we want you to do" and we had a guy who, we were designing affinity messaging, inspirational messaging or symbols on a small index card that you could look at for inspiration, or you can hand to your buddy or something like that. It was before we started really getting into doing masks and we were trying out different things that we, you know, what would work. And it was a group of burly men, and I will just say that much, burlier than me with real long beards, right? And you don't want to go down the wrong alley and have to negotiate with these guys 'cause they would take your lunch, for sure. They all did it, except one guy, crusty old guy. Really nice guy but his card sat there and at the end of the 45, hour, whatever it was, it was completely blank and there was nothing on it and he didn't do anything on it. And it was interesting where we went around the table then - it was a small group, it was like ten veterans - and said, "Okay, what did you write? What was the reason behind it?"

Todd Burkhardt: But he wanted to say his piece and it was interesting because he didn't do anything, and I think at the end, maybe he just wasn't paying attention to everybody engaged in the room, but he wanted to then say, okay, well I left mine blank and this is the reason why. I think towards the end he recognized that everybody else was doing this as a way just to express, and it's okay, man. Nobody's poking fingers at somebody saying, oh you can't draw or, oh you're doing something that's feminine, you're using crayons, right? And it was just interesting at the end, he was like, "Yeah, I want to talk about mine." And it was interesting 'cause he did nothing, he didn't even pick up an oil pastel but he wanted to express himself and be part of the group 'cause they all expressed themselves and they all did something.

Todd Burkhardt: So, it was interesting, right? 'Cause we've had some people like that but for the most part when we give guidance or talk about stuff, people do it. And then I try to move around and talk to different people just to get different perspectives on stuff, and the art therapist will walk around or sometimes we have people who have a Masters in social work that facilitate art-based wellness. Where our art therapist does art-based wellness but also art therapy, proper. And one of the things we're hopefully looking to do in the future is expanding aperture of what we do for art-based wellness. So, right now, we have a yoga instructor who is also a trauma therapist where, hey, we'll come to your town and we'll do yoga, man. So, it's great for mental health and well-being and do some exercise. In doing such, you don't ever have to have done yoga before. So, we've just added that to the repertoire.

Todd Burkhardt: And one of the things that we've talked about just we haven't had really a chance to talk about it in depth or maybe find some money but hand drumming. And so when you talk about masculinity and pounding and beating and building a sweat, we think that there will be veterans, men and women. Of course, men, right, 'cause oh you want to do something manly? Well pound this drum. But another way of expression, you know, opening up that large framework of art and also just recently added Tai Chi as well. We also partner with PALS, People and Animal Learning Services, here in Bloomington, and we do art-based wellness and equine-assisted activities. We've done multiple events with them over the summer and that is just a remarkable experience for non-riding but a remarkable experience.

Alex Chambers: This feels great to me.

Todd Burkhardt: Well, thank you so much. This was wonderful.

Alex Chambers: Thanks for willing to be open and present emotionally.

Alex Chambers: Todd Burkhardt. Todd is the director of campus partnerships at the Indiana University Center for Rural Engagement. His book, Just War and Human Rights, came out in 2017. It argues the "just war" theory needs to focus more clearly on human rights.

Alex Chambers: So, after I stopped recording, Todd and I talked a little bit more about what was happening when the vets came in and did art together. I'd been struck by how doing the art gave them a space or like a format to talk about their experiences. That seemed like the most powerful part of the whole process to me. Maybe even transformative. So, I want to end by asking what can happen when people get together and share stories. One thing that can happen is politics. If you've all shared the same experience, suddenly it's not just your personal experience and that might make you ask where it came from and it might even lead you to get people together and try to do something about it. And what can come of that? Well, it depends on what you decide to work on but if there is something that you're wanting to do, one place to start might be to get people in a room together, talking.

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/innerstates. And if you're listening to the podcast, feel free to leave us a review on Itunes or Spotify that will, as you may have heard, help more people find the show.

Alex Chambers: Okay, we've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Avi Forrest, LuAnn Johnson, Jack Lindner, Yane Sanchez Lopez, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Special thanks this week to Todd Burkhardt and the Indiana Center for Rural Engagement for helping make this episode possible. Alright, time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: Spring is coming! Or it was one morning in February, at least. Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks, as always, for listening.