Unknown male: We got your cat in a cage, and we got the picture, and the wife and I both think it's your cat. Wild as can be in this cage.

Alex Chambers: But is it Kayte's cat? Or is it another impostor like the last time she got a call from the man with the cage?

Alex Chambers: This week on Inner States chapter four of The Third Time Rita Left. But first comedian Mohanad Elshieky talks with Avi Forrest about how being funny in real life and on stage are not the same thing. That's coming up, right after this.

Avraham Forrest: Thank you, thank you, thank you. This is the Inner States show! I'm Avraham Forrest and tonight's guest is comedian Mohanad Elshieky, with musical guests from Universal Production Music.

Mohanad Elshieky: Avi, what are you doing?

Avraham Forrest: Nothing, nothing, just recording audio for the comedians story, the intro for the comedians story.

Mohanad Elshieky: Oh, okay, cool, go ahead.

Avraham Forrest: Tonight, on the Inner State Show, I'm Avraham Forrest and our first guest is Mohanad Elshieky. He's had his own TED talk, he's been on Comedy Central and some smaller shows like Conan, but now he's finally here. So, please welcome to the stage, Mohanad Elshieky.

Mohanad Elshieky: Especially in the entertainment industry, people love to just, like, give you a label and just be, like, be this guy. You're like the trauma guy, you're like whatever guy, you're the immigrant guy, because it's easier for them to package it and sell it as a product; because that's how they see you, you're just a product.

Avraham Forrest: Hey there, and welcome to The Comedians, a series about comedians. This time we're talking about Conan, trauma and what it's like making jokes when you're happy.

Conan O'Brian: Please welcome, making his television debut with us this evening, the very funny, Mohanad Elshieky!

Avraham Forrest: What was it like on Conan?

Mohanad Elshieky: Oh, that was fantastic.

Mohanad Elshieky: I would say the first 30 seconds were kind of like, I wasn't sure yet because before you get your first laugh, you're not sure how that is gonna go because it's a different set-up. You have five cameras pointing at you. You have an audience at 4pm.

Mohanad Elshieky: You have Conan and Andy just sitting not too far from you. So it's kind of like that's not my everyday set-up when I'm doing stand-up, and I also have five minutes and it's TV so I can't really riff. I can't go back and say something again, but overall I loved it, I loved it so much. I thought it went way better than I expected it to be and also Conan and the staff and everyone was very nice and supportive. They let you know what to do beforehand and where to look and all of that stuff and they're like, "Hey, this is gonna go great."

Mohanad Elshieky: But yeah, I felt like I was very well prepared for it, even though the process itself of getting on Conan took so long. I think it took over a year it was just back and forth talking and working on the set, arranging stuff and maybe sometimes "I have this new joke that I want to try instead of this one."

Avraham Forrest: Growing up, or just in your life in general, who were your comedic influences?

Mohanad Elshieky: Comedic influences? I mean honestly when I first started tuning in to comedy, I didn't even watch it. I remember my friend gave me a flash drive that had MP3 recordings on it. Some of the comedians I don't even remember who they are. I just remember listening to them and just liking the form of stand-up and all of that stuff. I remember one of the first people I saw was Russell Peters for example, just because he has so many videos on YouTube and stuff.

Mohanad Elshieky: I mean, a lot of the people, I wouldn't call them influences, they were just my intro to knowing what stand-up is. I've watched some Defense Comedy Jam and all of that, just to know what the form was. I can't say that I have specific people I can name in my mind about who are the influences, just the collective in general.

Avraham Forrest: So what is your vibe as a comedian?

Mohanad Elshieky: My vibe is that I'm just very dry on stage.

Mohanad Elshieky: I'm originally from Libya, which is a place that shows up if you Google it.

Mohanad Elshieky: I'm very dry, I wouldn't call it sarcastic but kind of that way. I love doing a lot of building throughout my set, just so I can do call backs and all of that stuff. I wouldn't call it observational humor, even though it is in a sense.

Mohanad Elshieky: I was driving my car and I got stopped at a checkpoint, and one thing you need to know about Libya back then it was mostly controlled by religious extremist militias. Then they searched my car up and down and then one of them looked at me and he was like, "Well who the fuck are you..."

Mohanad Elshieky: But yeah, once I'm on stage, I just try to be as confident as I could be.

Mohanad Elshieky: "...and what are you doing here?" And I was like, "Well, to be fair, I do ask myself the same question every morning, so I get it, bro."

Avraham Forrest: And it's very intellectual, it's very political, which I wouldn't say it's a rarity but I would say it takes some finesse to pull off.

Mohanad Elshieky: Oh, absolutely yeah because, I mean, it's easy when I am in New York, LA or even Bloomington, you know, because you do have a lot of people who already agree with you. But sometimes I go to parts of the country, like I'm in North Carolina or wherever, and you are not guaranteed to have a lot of people who politically align with you or are not as progressive as you are and all of that stuff. So, I won't say it takes convincing because I'm not trying to convince them of anything, but it takes a different arrangement and maybe I start, not going on all heavy at first and just taking them in slowly.

Mohanad Elshieky: Have you guys seen opinions lately? Yeah, they're really bad. And I also have opinions, but they're good.

Mohanad Elshieky: So even when you are saying stuff that they maybe don't agree with in their everyday lives, they will still listen and think it's funny and just enjoy it.

Avraham Forrest: When you're performing, would you say that you're a different person?

Mohanad Elshieky: Yes, once I'm on stage it doesn't matter what's happening in my life at that moment. Literally, the worst the thing could happen an hour before the show and then I can go on stage and just get into the mindset and everything else I just put it on the side. And I also know what I'm doing on stage, I'm very confident on stage. I have confidence on stage that I don't have in my everyday life, because I know exactly what I have to offer and I know exactly how things will work, so it's 90% planned. I like planning and I like knowing where I'm taking stuff. So yeah, I feel like on stage I'm a whole different person. Sometimes I wish I am that person who is on stage always because that would make my life so much easier!

Avraham Forrest: Off set, would you say people think you're a funny person?

Mohanad Elshieky: I hope they do because I am on stage how I am off stage.

Mohanad Elshieky: So I put my opinion out there and I believed in everything said until that guy Kevin replied to me. Do you guys know Kevin from social media?

Mohanad Elshieky: I talk the same way, I communicate the same way, so I believe that people think that. That's the reason I started doing comedy because people kept telling me that I should do this on stage, whatever it is that I am doing in conversation.

Mohanad Elshieky: Yeah, he's there. Kevin replied to me and this is what Kevin said, his reply was amazing, it was like poetry. He replied and said, "You fucking Muslim. I eat bacon 24/7," and I was like "Wow, what a hateful haiku. That's so cool!"

Avraham Forrest: Why do you think people kept saying you should do comedy?

Mohanad Elshieky: I don't know, I feel like a lot of people do get that though. Someone who's funny in their office or something, "Like, oh my God, you should totally do stand-up comedy," even though they shouldn't. I think people just thought I had something to say, or the way I deliver stuff fits within the structure of stand-up comedy, because there are so many ways to be funny but there are very specific ways to be funny within the stand-up comedy world.

Avraham Forrest: I've heard the sentiment that a lot of comedy is based on baring yourself to an audience, a lot of trauma to an audience. Would you agree with that?

Mohanad Elshieky: In a sense, yeah. I mean, some of it is deeply personal and all of that stuff, and I have stuff that is hard to talk about, and I have to kind of figure out how to do it in a way where it doesn't feel like that. Also it's the cliché of comedy plus time. When something bad happens, I try not to talk about it on stage immediately because there are so many emotions still attached to it, so you're not far enough from it to talk about it yet. But I'd also say that I have never written better jokes than when I was just happy.

Mohanad Elshieky: I feel like the stigma on stand-up is, especially with newer comics is that somehow you have to be miserable, and you have to be really going through it for the sake of art and for the sake of this Van Gogh-like syndrome where people have to feel like they have to be this tortured soul in order to make content.

Mohanad Elshieky: I'm just like, "No, you don't have to be that." You can be happy and still make good observations and maybe talk about painful stuff from the past, but it doesn't have to come on the expense of your mental health. You don't have to feel like you have to keep suffering and going through it just for the sake of content. I feel like that's something I would love to see gone from the stand-up comedy world because it's just not fun for anyone involved.

Avraham Forrest: And I guess, with that in mind, what is your process of making jokes, of making a set?

Mohanad Elshieky: The initial process is that a lot of these jokes really just come up with conversation with other friends and stuff like that. I would be telling them a story, or something would come to mind and they laugh at it and I just take my phone out and make a quick note, just to remind me to think about it more later. Then, I'm not a person who sits down and writes or opens a notebook and start writing and all of that. I don't really know how to do that, and it's not something I enjoy. What I do is I take these long walks every day in the city, and I just talk to myself out loud, where I imagine myself being on stage and I just perform it that way. By the time I am on stage, I have performed it enough times that it just doesn't feel new to me anymore. Usually, when I have a bit at first it's always kind of long. It's, like, three minutes, because you have all of that extra stuff that you're not sure if it's funny or not, or you're not sure how to get rid of it.

Mohanad Elshieky: I would do the joke over and over again, and every time I would change the structure, make it shorter, make it shorter, see what people laugh at. And then eventually, I don't think a joke really gets to it's final form ever until you tape it for something or put it on a special, so I always keep changing stuff. Sometimes, you have an idea you really like and you try it on stage multiple times and it just doesn't work, even though you think it's funny. Then I just put it on the side and sometimes a year from when I tried it, I finally figure out how to do it. I have another joke that fits in well with it or I have a story that this could be a good tag for. I never really get rid of stuff, I just put them on the side and eventually find a way to re-purpose them. I have jokes from three years ago that I literally just started doing again now because I figured out how to do them.

Avraham Forrest: For those things that are based more on those more negative experiences, what's it like turning negative material into comedy?

Mohanad Elshieky: It feels good just saying stuff out loud, sharing them with people and actually being able to talk. Because once it's funny it doesn't feel scary anymore, it doesn't feel like as bad. It's still bad but it's not as bad once you could make fun of it. I get to a point where I start telling these stories, and it feels like I'm talking about another person who's not me. You feel like you are separate somehow and just watching from the outside, so it does help you get over it. But in the same sense I would say that I don't think of stage as therapy. Because I know comedians love saying that comedy is their therapy and I just think therapy is therapy and maybe people should do that instead. The audience is there to enjoy their time and have a good time. They probably got babysitters for their kids and all of that stuff, and I'm not gonna just go up and use them as a way to process my emotions. There has to be a balance there. You should be able to talk about whatever you want to talk about, but at the same time do it in a way that does not make people just not enjoy it because you haven't processed it in the outside world yet.

Avraham Forrest: A lot of your work brings up arguably important topics and important perspectives. Honestly, I would argue that humor can be activism.

Mohanad Elshieky: It's easier to do it within stand-up comedy because it's packaged in these jokes and stuff like that. People are more able to listen to them and they can relate to you and all of that stuff. I mean, humor does humanize you more so in a sense, yes, it can be a form of activism. But I'm saying at the same point, I'm kind of in the mindset that my goal is to make people laugh, to make them enjoy the show, and I'm glad if a positive change happens. I can't say that I sit down and write jokes and say, "This is what I want to happen." You can never control how people take your material and jokes, and how they understand them and how it resonates with them. Sometimes you have a joke that has a really big impact on someone, and sometimes it's just a funny joke that they remember. You can't really control that, you just hope for the best when you write them.

Mohanad Elshieky: One last thing, I had this really terrible thing happen to me a few months ago. I was doing comedy in the city of Spokane, Washington. Yeah, one person knows that place, the rest of you, you don't need to, it sucks, the worst place on Earth. It should be canceled honestly, can you do that? Yeah. I was doing comedy in a very small city, very white, very Republican but I did comedy there because why not?

Avraham Forrest: More recently you shared that experience about being taken off a bus by border patrol.

Mohanad Elshieky: And then, as I finished my set, I got on the Greyhound bus to go back to Portland where I live, because I believe that the best art comes from torture, you know? I was on the bus, everything was great, I'm just looking at my phone, just scrolling down like, "I wonder what Kevin has been up to lately." Then I see people wearing uniforms and they get on the bus, and they start asking people questions. And then one of them looks at me and he was like, "Oh you don't look like you're from here. Where are you from? Can we see your papers and everything you have, and let's step outside of the bus." Then I learned that these people were Border Patrol, and it's obviously very disgusting because they asked me to step outside of the bus based on the way I looked. They looked at me and they were like, "This guy looks too handsome to be from Spokane. He has most of his face." They looked at my papers and they're like, "These papers look fake, they're easily falsified." And I was like, "Well, these papers have been given to me by you, so maybe do a better job? I don't know, that seems like a you problem at this point." Then they were like, "Okay buddy, one more thing. Are you from Oregon or Washington?" I was like, "I support God." They were like, "What does that mean? I was like, "I don't know man, that's how I talk to militias."

Avraham Forrest: Are you ever afraid of being pigeonholed as someone who has had that experienced and people only want you to talk about that experience?

Mohanad Elshieky: Yeah, of course, you always feel that way. You're like, this is the only thing people wanna hear about and all of that stuff, and I get it, because it's just obviously a very big event and all of that. And this is how people got to know me because this story was on the news and all of that stuff. But I think what helps the most is I usually get to do a full hour of comedy or so and people come see me, so they get to see other stuff as well. That Greyhound story for example is four, five minutes out of a 60-minute set.

Mohanad Elshieky: They get to see the other aspects of me and sometimes I don't even talk about myself. I can just have silly observations about other stuff that I think are funny. I think it gives people more of a way to see you as a person who is multi-faceted and all of that stuff, and more like them than anything than just one story that you have.

Mohanad Elshieky: It's always a fear and, especially in the entertainment industry, people love to give you a label and just like, "Be this guy." You're the trauma guy, you're whatever guy, you're the immigrant guy, because it's easier for them to package it and sell it as a product because that's how they see you, you're just a product.

Mohanad Elshieky: I think just because of how social media is now, and how there are so many ways to communicate with the audiences, there's more freedom now to package yourself the way you want it, which just as a person, whatever you want it to be.

Avraham Forrest: Seeing people of color and immigrants as not just their trauma and just this one thing that happened, and seeing them fully and seeing that they're just people and like you said, they're not machines for money, they're not like vehicles for traumatic stories, they're people.

Mohanad Elshieky: Exactly, yes, absolutely. That's the thing, and that's one thing that stand-up allows me to do. It allows me to not just tell my story, but talk about myself and my personal life and all of that stuff, but on my own terms and not having to do it the way people want me to do.

Avraham Forrest: Yeah and I am not an immigrant, nor a person of color. I am trans, and I sort of identify with this concept of like, I would feel weird if I was reduced to my traumatic memories because I think trans-ness is reduced to the dysphoria, and there is joy within it, and I'm really just a person.

Mohanad Elshieky: Exactly. You just want people to be people and that's the whole of it. Especially if you are someone who is supportive of trans issues, or you are an ally to people of color and all of that stuff, it shouldn't come on the expense of them having to relive their trauma over and over again just to prove that they are people. People in general just deserve to be happy and just live their normal lives, without being reminded that they're different, or need to do more work to be accepted or any of that stuff.

Avraham Forrest: What are you afraid of most as a comedian?

Mohanad Elshieky: The fear is always not connecting with the audience and bombing. I don't care if a joke bombs, like one joke, but if the whole set is not going your way and you have to be up there for an hour, that is not great. Also it's not a fear, this is more of an inconvenience, but you travel all the way to the city or something but you do not get the turnout that you expected. You have this really great hour and maybe 15 people show up out of 100 or something and you're like, "Well, I mean, it is what it is, you just got to push through it." Especially, I guess that's the fear, an irrational one, when you have a writer's block and you're like, "I don't think I can come up with jokes anymore, that's it for me."

Avraham Forrest: What is something you haven't been able to achieve?

Mohanad Elshieky: I wouldn't say not able, it's just a lot of this stuff takes time. I would love to have my own TV show, which is something I've been working on. It's just that stuff like that takes so long and it's such long process. I wouldn't say I wasn't able to achieve, it's more like I just wish it can be achieved quicker. In my mind, I have a lot of clear goals, and I have confidence enough in myself that I know that they will happen eventually. It's a matter of when and not if. I just hate having to wait for too long.

Avraham Forrest: What is something that you want people to know about you?

Mohanad Elshieky: I don't know if there's something I need people to know about me, but it mostly has to do with comedians in general. Just because you see someone on stage, or you hear them on a podcast or something and you know so much about them, you shouldn't assume that you know them, I guess. Sometimes I would get DMs on Instagram or whatever and people are just, because they hear you and they listen to you, they get too familiar, they get too comfortable. It's like, "Sorry, you don't know me that way." Sometimes it's kind of weird, you know me but maybe I don't know you in that sense.

Mohanad Elshieky: If there's anything I want people to know about me, honestly, is that I have two cats and I love them so much. If I am to be pigeonholed into any label, it would be that I love my cats, because I do not mind that.

Avraham Forrest: What are your cats' names?

Mohanad Elshieky: Their names are Una and Tuney, together we call them Tuna. They are three years old and I love them so much.

Avraham Forrest: I think that's gonna be the focal point of this interview, honestly. There will be some minor notes about your work.

Mohanad Elshieky: I would not mind that. I literally would not mind it if you even put their name on the headline and not my name.

Avraham Forrest: [LAUGHS] The show is called Inner States, but it's gonna be called the Tuna Show from now on.

Mohanad Elshieky: Perfect, amazing. Yes, I love that.

Avraham Forrest: Thank you so much. That's all I have for today. It was amazing meeting with you, I think your work is just so essential and I love your comedy.

Mohanad Elshieky: Thank you so much, appreciate it.

Alex Chambers: Comedian Mohanad Elshieky talking with Avi Forrest, who is not the host of this show, at least not yet. Mohanad came to Bloomington as part of the Limestone Comedy Festival in June. Okay, we have the last chapter of our missing cat story soon, but first a break and a quick look back at a recent episode. Stick around.

Alex Chambers: Inner States. Alex Chambers. The last chapter of our missing cats' story is called Rita's Village and a lot of this story has been about people coming together to save a cat. So before we conclude Rita's story, I want to remind you about an episode from a couple of months ago that was also about community in a different way. Kara Schmidt and Andy Gerber live in an old tomato products' factory building in Paoli, Indiana. They've turned the place into a community center, they run a festival, Paoli Fest, they teach yoga classes, make and sell bagels, host lecture series. The building's become a kind of community hub. Before that they'd been living in Chicago. They had thought they could build a community there, but it was harder than they expected. They had a place in Goshen, Indiana and they were trying to figure out what to do next.

Andy Gerber: And then my sister died, Kara's dad was dying, lots of things were shifting, we sold our house in Goshen and bought this place all within, like, two months.

Kara Schmidt: The Eubanks bought this place in maybe the late 60's, and when they bought it, the building didn't have floors, there was no roof, there were probably no windows because of the fire that happened in, like, the 40's. This was the warehouse for the tomato factory and there were other buildings/structures that were actually like cannery that got so destroyed in the fire that those buildings got demolished eventually, but this one was left standing enough, but really didn't have floors, it didn't have a roof. So the Eubanks bought it to put in a small furniture factory. They're the ones who, like, saved the building really. Didn't they build the front? On this big patio out front they built a structure that was, like, their offices and maybe bathrooms and things and then the rest of the main part of the building was the factory and they put like in a little elevator so they could move things.

Heather Nichols: The very end of them owning it, I was a little kid, and I remember my dad, because these are my dad's cousins. My dad tells the story, I've told you this, about how they always would come up and walk the railroad tracks and there would be little cacti from where the railroad had gone out west and come back. There were cacti growing in the railroads there. When the railroad was still running. Is it crazy to think we have vague memories of the railroad or was that long gone?

Kara Schmidt: No, I kind of do too.

Heather Nichols: But I don't know if I'm just thinking I remember that.

Andy Gerber: The railroad was decommissioned in the 80's.

Heather Nichols: Yeah. But my dad would come up here when he was young and he remembers there being little cacti from when they'd go out west and come back. And even if it's not true, I like that story. Yeah, it was woodworking. I just remember lots of wood smells when they had it, but I don't know who had it after that, or nobody had it.

Kara Schmidt: I don't know either. At some point after the Eubanks, somebody bought it and made it a pallet factory. I think that's the Lows. There's been a haunted house here, like in around '94 after I had gone, and then besides that it was just used kind of as storage. We bought it from a guy named Willy Sprinkle. He's not a native to Paoli. Also owned the house that burned seven years ago. It was our first winter here.

Heather Nichols: I remember watching that fire, not sure where it was and kept telling Jeremy, "You're going have to go, you have to get in your car and drive and see if Kara's house is on fire." He was like, "It's not her house." Of course, he was right again.

Alex Chambers: That was Andy Gerber, Kara Schmidt and Heather Nichols in our Postcard from Paoli from early June. You can hear the whole thing on the Inner State's podcast feed where, if you're into it, you can also rate and share the show. In the meantime, we're going to take another break and then get back to our cat.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers. It's time for the last chapter of our missing cat story. If you've missed any of the previous chapters, feel free to turn off the radio or stop the podcast and go into our podcast feed, you can find all four of the chapters on their own, separate from the scintillating but maybe distracting parts of full Inner States episodes. Or maybe you have heard those and you're ready for the conclusion? Well, here it is.

Alex Chambers: Rita ran away in September. October came and went. Kayte missed her so much on Halloween that she carved Rita's image into a pumpkin.

Kayte: What was amazing is that it really did look like her, like it captured something about her face. And I posted that on Facebook and somebody said something like, "Oh, it's a beacon to Rita, calling her home, you know."

Alex Chambers: But she didn't come home. November rolled on, Trump became President Elect, the weather got colder and still Kayte wandered through fields and neighborhoods, trying to find her cat.

Alex Chambers: All that wandering gave her time to think. She thought about cats and survival, about presidential politics and about race and privilege.

Kayte: And the ability to kind of roam around in people's spaces, you know, private spaces and not be a threat. That was something that I feel like I thought about a lot, when I was out there walking around by myself. I also thought about the vulnerability that I had, just as a woman, wandering around alone, and the fear of male violence that is always present when you're a woman and you're out alone after dark. But that wasn't as strong for me. I didn't feel it that much. Mostly I felt safe and protected.

Kayte: And so that was kind of a physical revelation. It was something that I already knew on an intellectual level, but like being out there, doing this thing that I really felt like I needed to do, and that if I wasn't a middle class white woman approaching 50, that, you know, I might have seemed more threatening and I might not have actually been able to do this thing that I wanted to do. My freedom to do would have been limited. My freedom to approach people and have them respond to me kindly.

Alex Chambers: As we've discussed before, how we appear in the world affects how people react to us, whether it's age, gender or race, or just the fact that we're unusually beautiful, as you might remember is the case for Rita.

Kayte: People kept saying, "That is such a beautiful cat."

Alex Chambers: That may be why people kept going out of their way to help, calling out Rita's name in the middle of the night, burying dead cats and then thinking, "Oh, maybe that was Rita. Maybe Kayte should come dig it up." There were a lot of good intentions out there, but you know what they say about good intentions, the road to hell is paved with missing cats. The only good thing about going down that road is that the destination would have been warmer than winter in Bloomington, and if you're wondering what my point is, it's that at this point in the story it's December, and if Rita survived this long it's going to be harder in the next few months. Kayte needs to find her soon.

Alex Chambers: When you've been searching for a cat for months, and you get a call from a man with a horse, who says he's seen your cat in his barn and that barn is not too far from the last place you saw your cat...

Kayte: I could picture her traveling that distance.

Alex Chambers: ... and you're standing in line at the bank with your husband and son when you get that call, you leave that line. You get in your car and you drive over to see the man with the horse.

Kayte: He had a field behind his house, but then there was also a neighborhood right there. So we looked around in that neighborhood and we saw this cat, and at first we thought it was her and we went up to her and it was not her, it was a long-haired calico, very friendly. We petted her and stuff and we were like, "Oh, that's probably the cat he saw and he thought it was her."

Alex Chambers: At least this impostor was alive.

Alex Chambers: They told the man they'd seen her in the neighborhood and it wasn't Rita and he said, "I don't think that's the cat I saw."

Kayte: And we didn't really believe him. We just felt like he just wants to help and, you know, he means well, but he doesn't know what our cat looks like.

Alex Chambers: Doesn't know how beautiful she is, is what Kayte means, so they go home. A couple of weeks go by, another call comes in.

Kayte: "I saw your cat. I know what she looks like. It was your cat. She has been eating crumbs off of my deck," like cracker crumbs or something, which I thought was a little unlikely.

Alex Chambers: Because you'd only leave cracker crumbs all over your deck if you were trying to attract wild parrots and, you know, there's only one parrot in Bloomington and it goes around by bike, so it's probably not coming to your deck. But Kayte realized that if there was a cat eating those crumbs, it was probably a desperate hungry cat, because who else would eat crackers off a stranger's deck? It seemed like it might be Rita.

Alex Chambers: So Kayte and Carl went out. It turns out it was right near the barn where the man with the horse had seen the cat he thought was Rita, which made them think that they should look in the horse barn again. So they talked to the horse man and he said, yes, he'd seen her since Kayte's last visit. "The next time I see her," he told them, "I'm going to try to trap her." He's convinced it's her. Kayte and Carl say, "Okay, sure. Go for it. Thank you."

Alex Chambers: As they turn around to go home, they're thinking, if that really was her, she could be so close right now, she could be behind that house, hiding in that brush or around the side of that barn. She's on their minds, so they decide to stop in the old neighborhood again, Peppergrass, where the real live Rita escaped from Kayte's arms. Occasionally they'd stop over there, put out food, walk around, call her name.

Kayte: And it was getting cold, like it was December, it was late December, and Carl, I will never forget this, he put out some food and said, "Here you go Rita," and there was a little crack in his voice, like he was about to cry. And I just realized he was just as sad as I was about this. He was just as torn up over it. He missed her. He maybe didn't cry about it and talk about it all the time like I did, but he was feeling it.

Alex Chambers: Even the people we spend more time with than anyone else, sometimes we don't know what's going through their heads. Kayte went to bed that night with new insight into her husband, but still no Rita.

Alex Chambers: It was almost winter and the world looked grim. A man who'd lied and cheated and assaulted his way to fame was about to become the U.S. President. The UK had narrowly voted to harden its borders with Brexit. Alton Sterling and Philando Castile's deaths at the hands of police were still echoing alongside a homophobic terrorist attack at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. In South Dakota, police were using armored personnel carriers, batons and tasers to push members of the Standing Rock Sioux and other tribes off the land they were trying to protect from the Dakota Access Pipeline, and Rita was still unaccounted for, probably alive somewhere nearby but they couldn't be sure.

Alex Chambers: The next day, Kayte had a meeting to get to. She knew the people she was meeting with, it was about a project for her son's school, and they knew about the search for Rita, as did everyone Kayte knew, and because of Facebook, hundreds of people she didn't know. She was on her way to the meeting and she got a voicemail. It was the man with the horse barn and it seemed like really good news. Such good news, we decided to go digging in the archives for this message, and I am happy to say the archives came through.

Man with the horse barn: We got your cat in a cage and we've got the picture and wife and I both think that's your cat, wild as can be in this cage. So give us a ring and tell us when you can come. I'll keep it in the cage until I hear something.

Alex Chambers: He'll keep the cat in the cage until he hears something. Whatever cat it was, it wasn't going anywhere, but still it felt urgent. Kayte told the people at the meeting. They were excited and told her she had to go. She texted Carl. He picked her up and they drove to their son's school. If it really was Rita, Cosmo needed to be a part of this, just like he needed to be there when they dug up the dead cat. You never know when it will be the one you're looking for.

Alex Chambers: As they drove down there, Kayte and Carl made it clear to Cosmo that this too might be another false lead. It might not be Rita they warned him. It wasn't just Cosmo they were preparing for disappointment. So they arrive at the house, they head up to the porch, each asking themselves if it's their cat in the cage up there, each wondering if it's Rita or another impostor. There have been so many. They see the cat, it's scared, it's howling and...

Kayte: It is our Rita!

Alex Chambers: They'd found her. She was thin and dirty but alive. Kayte thought it was a dream. She was scared they might not be able to get her home, she might slip away again. One thing was clear...

Kayte: We were not going to get her out of the trap until we got her home so.

Alex Chambers: The man said they could take the trap with them, so they put her in the car.

Kayte: Got home, brought her inside, brought the trap into our bedroom, shut both doors to the bedroom and then let her out of the trap. I think the first thing she did was run and hide under our bed, but then we like put some food out and we talked to her and eventually she came out and she drank water and ate food. She wasn't skittish for very long. Like she seemed to recognize that this was home and that we were the people she knew, and she started purring and she relaxed and she was okay.

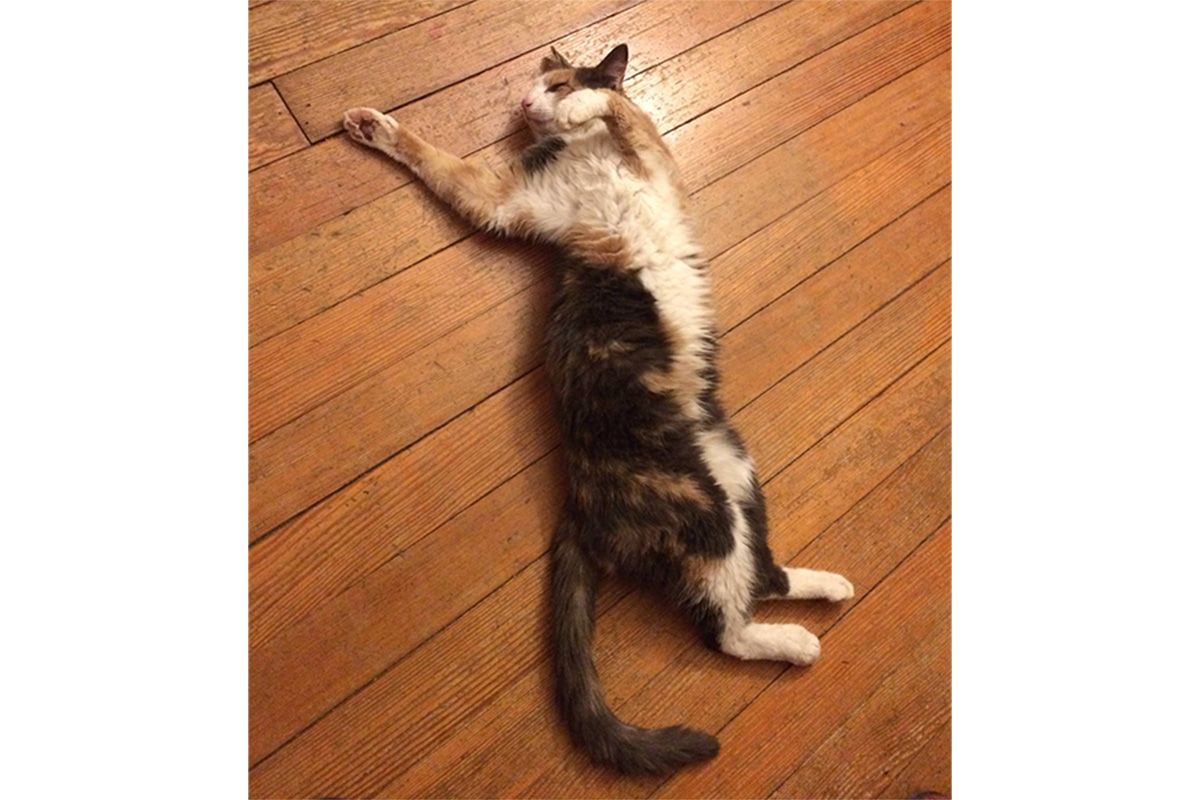

Alex Chambers: When you haven't seen someone for a long time and you get back together, it can be a little nerve-racking, will it feel as easy as it did before? Often it does. It didn't take long after Rita got home for her to start doing her signature move again.

Kayte: She just kind of lays down on her back and then really stretches out, and then like her feet are going one way and her upper paws are going the other way and she's like in this spinal twist, and it's such a perfect like yoga posture. Every time I see her do it I'm like, "Oh, she's so smart, I should be doing that," you know?

Alex Chambers: And she purrs. In the household they call that purr Rita's roar. Don't worry, they've checked her out, she's fine. Kayte thinks Rita probably didn't do a whole lot of spinal twists in the three months and a week that she was on her own.

Kayte: When you're in a survival state, whether you're a person or you're an animal, and domesticated animals have this kind of leisure and ability to like relax and lay down and expose their tummies and do spinal twists, and you know like really chill out. And I always felt like when she was out there in the wild she would never have that ability to do that, because she was in danger or she felt like she was in danger, and so she would never be able to lay down and do a spinal twist for instance.

Kayte: I think that's also the case for grooming, I think that you can only groom when you're safe enough to groom, when you're a cat. Like you have to have a level of protection before you can really like focus on grooming your whole body for however long that takes. And so that's why she was dirty when she came back to us, because she's a very clean cat, both of our cats are always just immaculate. So sometimes nowadays when Carl's like scratching her chin, he'll say, "Remember when your chin was dirty? Remember when you had a dirty chin?"

Alex Chambers: All right, we've come to the end of our story. If there's one thing I want you to remember, it's that Rita only made it home because of all the people keeping their eyes open for her, even though they didn't need to. I think there's something in that about the harsh realities of the world we live in. We need each other. If there's a lesson here, it's that it takes a village to catch a cat, and to take care of one in the first place. I mean Kayte said even the carrier, the one that broke and let Rita escape, that came from a family in Cosmo's class. They don't have it anymore.

Kayte: We destroyed it and I've always kind of secretly resented them.

Alex Chambers: I guess I want to end with a message for Kayte herself because she's a good friend of mine too. So Kayte, I know how guilty you felt about Rita's escape, but I think what we can learn from all this is that it takes a village to lose a cat too.

Alex Chambers: That's it for our story. If you liked it, tell a friend. In the meantime, I have a few friends and colleagues I'd like to thank for helping me put this together. Most of the music in, "The Third Time Rita Left" was composed and recorded by Ramón Monrás-Sender. Other music came from Backward Collective and Universal Production Music. Editing help came from Molly Weiler, Ross Gay, Essence London and Kayte Young herself.

Alex Chambers: This has been a production of Inner States, a podcast and broadcast from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or you've got some sounds we should hear let us know at wfiu.org/innerstates. We've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up but first the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Avi Forrest, LuAnn Johnson, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is Eric Bolstridge. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Special thanks this week to Mohanad Elshieky. All right, time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: That was one a.m. on a hot summer night. It was recorded by Patsy Ron in Bloomington. Thanks Patsy for sending it in. Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks as always for listening.