Alex Chambers: When Shaka Shakur wants to read a book he has to jump through quite a few hoops. He is in prison and he has to have a guard to take him to the library or get someone on the outside to send him what he wants. He wants to read about black history and liberation but it can be hard to get those topics past the mail room; they are often flagged as security threats. Shaka knows what he is missing. He is dealing with known unknowns but in balances in power to lead to unknown unknowns too. When Kaila Austin started learning the history of the Norwood neighborhood of Indianapolis she found troves of black history that was only known to the families themselves. The people in power hadn't seen this place as worth remembering so the history had stayed in all the womens garages and descendants attics. This week on Inner States Kaity Radde brings us two stories of knowledge and power. Then Kayte Young talks to a comic book artist. That's coming up after this.

Alex Chambers: This is Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. I'm Alex Chambers. This week we have two stories from producer Kaity Radde. The first is about Shaka, who is a facing a lot of obstacles to getting reading material especially it seems if that reading material has to do with black history and liberation. Here's Kaity.

Kaity Radde: Every September the public library down the street from my house had a display with caution tape all over it. It was banned books week. The table was full of stories that some parents, schools and religious organizations have fought to ban from school and public libraries. Things like Harry Potter, The Handmaid's Tale, The Most Dangerous Game. I found it so bizarre that some adults were so obsessed with what my peers and I might read. From then on nothing made me want to read a book more than finding it on a banned books list. But here's the thing. I was still able to get my hands on banned books pretty easily. If you are incarcerated, it is a different story. Prison book bans are absolute. If the book you want isn't in the prison library you have to buy it or someone on the outside has to send it to you and, if it gets to the mail room with a stray highlight or ripped cover, or if somebody in the mail room thinks reading about MALCOLM X might insight violence, that book you or your family or friends paid for will be rejected or destroyed.

Kaity Radde: Restricted book access is hardly the most intense violation of human rights that happens inside American prisons and jails. But it's a huge First Amendment violation and it cuts off a major source of education and entertainment for prisoners. Imagining myself subject to that situation made me claustrophobic for lack of a better word. It made me wonder how I would spend my time if I were caged by the State with even the smallest luxuries like choosing which books to read restricted to almost nothing. And it made me want talk to Shaka Shakur because books play an important role in his life inside prison where he has been for decades.

Shaka Shakur: [INAUDIBLE]

Kaity Radde: In 2018 IDOC transferred him to a Virginia prison. The law books he used to help himself and other prisoners work on their appeals should have been in his cell waiting for him but they weren't.

Shaka Shakur: All my law books and Britannica encyclopedia that I've had for the last 20 years, all these books were withheld. Now they've disappeared and I don't know where[INAUDIBLE].

Kaity Radde: Shaka spent almost 20 years of his 63 year sentence in Indiana where he is from. He had ongoing litigation in Indiana. Being transferred away without his home States law books made it difficult to meet legal deadlines and continue working on his case. Shaka said he's had trouble getting and keeping books regardless of where he has been. The Virginia Prison recently forced him to send home over 90 of his personal books which he shared with other prisoners. Most of them were legal and medical texts. He had exceeded his 13 book limit so the rest were considered contraband. He said he's been impressed with the Virginia Prison libraries compared to Indiana's though. Back in Indiana.

Shaka Shakur: They would deny most history books or my MALCOLM X and George Jackson but if you go to the library you've a ton of material in the library on Nazism,or [INAUDIBLE] or white supremacy and so forth. Back there it was no problem with that whole section of this type of real factors on that but, yeah, you would have basic books but some places even the autobiography of MALCOLM X would be denied.

Kaity Radde: Shaka is by no means the only person to experience this kind of thing. Prisons ban more books than any other institution in the US, according PEN America, and that's especially true for books of our black history and civil rights. They're disproportionately blocked to security threats. Like in other States, mail room staff in Indiana prisons use their discretion to decide what to reject. They are encouraged to err on the side of caution and they sometimes take the rules to the extremes and deny books that pose no meaningful threat. In 2018 five IDOC facilities began to only allow books from two vendors: Amazon and Edward Hamilton, and they rejected all used books. In mail room training materials IDOC said those facilities made the decision without approval from the Central Office. The Human Rights Defense Center is a group that advocates for prisoners rights and they publish magazines and legal self-help materials, and when that rule went into effect none of their materials were getting in. Dan Marshall is General Counsel there and he said they didn't even know that their was being rejected until their subscribers on the inside told them.

Dan Marshall: So there clearly are certain things that they can ban. There is no problem with them preventing prisoners from getting magazines talking about how to build bombs, for example, but in many places they expand that way beyond what is actually a legitimate interest of theirs.

Kaity Radde: So the Center sued in November 2020. By the way, the Supreme Court ruled way before all of this happened that prisons have to let senders know when their mail is rejected and why. Last January, a Court told IDOC it had to stop rejecting books based on the supplier. It also said IDOC has to notify whoever sent the rejected materials in writing and it had to say exactly what the part of the material threatened a specific legitimate, penological interest. You might be wondering why the Center's publications were being rejected in the first place. When IDOC was asked to say what exactly threatened the prison, the problem wasn't the text of the magazines at all. The problem turned out to be advertisements for pen-pal services which IDOC argued posed a security threat. How is that a security threat you ask? The Courts seemed to want to know the same thing because the settlement they reached last November specifically prohibits IDOC from rejecting material solely on the basis that they contained pen-pal services.

Dan Marshall: They agreed to ultimately settle the case in their publication set which if they truly thought there was a security problem they wouldn't have done that.

Kaity Radde: The settlement reinforced that prisons couldn't reject books based on their supplier. IDOC has to provide a reason for all rejections going forward and they also had to create a training program to make sure all of that actually happened. I took a look at the mail room training they have implemented. It went over the facts of the case and it explained the kind of things that should or shouldn't be rejected. But it said nothing about maintaining logs of confiscated material which the settlement requires. It also encouraged mail room staff to think broadly about ways in which a material could become threatening to the prison. Also, remember how the Court said IDOC has to state specific threats to its interests when it rejects material? A couple months after that Court Order, IDOC rejected a book from a non-profit called Books to Prisoners. The rejection letter said nothing about why the book was rejected.

Dan Marshall: Often times we'll get something back saying, rejected for racial content or will challenge the good order of the prison. Sometimes there is no additional explanation. Sometimes they'll point to a specific page which might refer to something or anything to do with race.

Kaity Radde: Andy Chan is a long time volunteer and current President of Books to Prisoners. Often rejections from prison systems all over the country come back with no explanation at all even though, again, Supreme Court precedent requires them to. But when they are given, reasons vary. Some prisons don't accept used books for example or books with stains or markings. Books to Prisoners has also dealt with content based bans which are bans for things like violence or nudity.

Dan Marshall: Very basic nudity sometimes National Group Geographic is one that we have to trawl through every page to make sure there isn't an errant nipple or genitalia of any sort because that will get rejected from most prisons. None can be as ridiculous as a case which rejected a book on renaissance art because there was a black and white reduction of a, I think it was a fifteenth century painting of the Madonna with baby Jesus and baby Jesus which was about half an inch to three quarters of an inch long and had a little baby Jesus penis, which was probably a millimeter long but that got the book rejected.

Kaity Radde: IDOC said its staff doesn't keep a record of the books it bans. That means it's impossible to say to what extent they reject books by and about black people as security threats. But anecdotally that pattern persists in Indiana.

Adam Scouten: So the IDOC particularly does not support political literature that is broadly pro-black.

Kaity Radde: Adam Scouten is an organizer for IDOC Watch, a prison abolitionist group that works with political prisoners. He said one of the main ways IDOC rejects black political literature without violating the law is through security threat groups. Law enforcement defines a security threat group as any group of prisoners who violate, or might violate, the prison rules. You'll hear them called STGs too. One publication Adam mentioned that gets rejected on these grounds quite a bit is the San Francisco Bay View national black newspaper. It publishes stories about San Francisco's black community and writings by prisoners all over the US.

Adam Scouten: If they find a book or publication that even so much as refers to an STG they will ban that book. We know that white supremacist oriented textshave been allowed to come in and so the focus is clearly on banning Afrocentric texts.

Nube Brown: They don't want our publication because it's educational, it's inspiring, it brings hope. Of course they don't want that.

Kaity Radde: Nube Brown is the Editor of the Sans Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper. For Nube these bans on books and newspapers are an extension of a much longer history.

Nube Brown: So I say mass incarceration is modern day slavery. Slaves are stripped of all their rights. If you think about chattel slavery, it was against the law. You could be whipped, tortured, killed for reading or writing. You were not to have any agency over your life. You were the property of the Master. Well, that is exactly what's taking place inside of our prisons. So, if the prisoners are educated about who they are, what is happening, and then maybe able to get together and resist what is taking place that of course is a threat to the system.

Kaity Radde: I reached out to IDOC and a spokesperson denied that they banned books based on race. For prisoners, just like for people on the outside, reading is a source of education, empowerment and entertainment. On the inside, it's also a connection to the outside world. Prison libraries are limited and you can only go if a guard agrees to take you. A company called Global Tel Link powers tablets that prisoners can use to buy e-books, music and movies but they are expensive and selection is limited. By the way, Global Tel Link is the same company that runs the phone lines Shaka and I used to talk to each other. Incarceration is a really big business. GTL makes hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue every year off of prisons and jails. Shaka said the move toward tablets and e-books is a way to both restrict and monitor was prisoners re reading.

Kaity Radde: When Shaka and I talked here was reading The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon and he had just finished a book about Gloria Richardson and the struggle to desegregate Wilmington, Delaware. A lot of the books he read are about decolonization, anti-sexism and the movement to abolish prisons; things that might help him to educate and to politicize other prisoners. Like Shaka said earlier, he has had an easier time getting books in Virginia and the prison library is better than Indiana's. But it is still frustrating when he can't get the books he wants. Adam is friend of Shaka's and his work as IDOC watch organizer brings him into contact with other prisoners too. So he has seen what it does to people when they are cut off not just from other people but also from literature.

Adam Scouten: You are sitting in a cell with nothing to do, and it gives a lie to the official narrative that a prison exists for reform and rehabilitation. The best way for people, and the only way available for prisoners to be able to make any positive use of their time, is really through literature.

Kaity Radde: On top of the need to occupy your mind while incarcerated not having books poses practical problems. Shaka was able to get new legal self-help materials but in some prisons and jails, legal books are rejected out of hand as dangerous. Why? Because they usually have hard covers.

Adam Scouten: So there is a million and one tricks they use to keep people separated from information that's essential not just for their own self-improvement or their wellbeing, but for their ability to be able to get out of prison eventually.

Kaity Radde: In the prison yard Shaka Shakur studies. When he first went behind bars at 16 he was just a kid. Older prisoners mentored him. They taught him about MALCOLM X, Fannie Lou Hamer, the prison movement in the American South. As he learned he would go out into the yard sharing what he learned with others.

Adam Scouten: He was learning stuff in prison that weren't learning at school and so it might be five, ten sometime as maybe as 15 or 20 of us studying, instead of playing basketball or what have you and we developed casted book reports off certain books and ran our own underground libraries.

Kaity Radde: He said rebuilding the current study groups infrastructure after he had to send home so many books will be frustrating and expensive. But he will reorder more and he will share them with others.

Shaka Shakur: In prison, knowledge is power and it's also a threat to the establishment.

Kaity Radde: It's not just in prison that knowledge is power. Why else would people be so up in arms thinking critical race theory is being taught in schools or panicked about their kids learning about queer people? If you ask Shaka, the panic in school board meetings is the same panic that restricts his book access.

Shaka Shakur: Oh it's the same thing with the prisons. As they're giving these tablets, etc, we can order e-books, etc, you limit it more and more. It's an agenda here. It's a strategy and that strategy is being pushed by the State in terms of more control, more surveillance, and so forth and so on, and trying to undermine the ability for us to organize the fight for our rights but it's behind these walls on this front, or behind the walls on that front, out there where you are.

Kaity Radde: Knowledge is threatening to people in power because it's a precursor to action, whether we're on the inside like Shaka or not.

Shaka Shakur: Nice to meet you, Kaity, I appreciate you.

Kaity Radde: Nice to meet you, Shaka, thank you so much. Bye.

Kaity Radde: From school board meeting rooms to prison mail rooms, people with power evaluate what people's subject to that power should know and they are not going to allow knowledge to be shared if it might help prisoners go on strike or lead school children to organize a walk out in support of black lives. At least, not without a fight.

Alex Chambers: That was producer Kaity Radde. A print version of that story originally ran in the Indiana Daily Student. It's time for a break. When we come back, Kaity brings us a story about what can happen to a neighborhood when a city decides its history doesn't matter. Stay with us.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. Part two of our show today is about a neighborhood in Indianapolis whose history, stories and archives have been ignored by city officials for generations. That's affected more than just what stories we have. It affects what gets built and what doesn't. Kaity Radde brings us the story.

Kaity Radde: Norwood is a black neighborhood on the south east side of Indianapolis. It was founded as a free town by emancipated slaves in the reconstruction era and it became a tight knit affluent black community in the late 1800s and early 1900s. But for most of Indiana history you would be hard pressed to find any of that if you turned to the State's museums, libraries and archives. You would find materials portraying Norwood as a decaying neighborhood if you found anything. A group called South East Neighborhood Development got a grant to create the Memory Keepers Project which began collecting stories from elders in Norwood and nearby neighborhoods. They commissioned Kaila Austin for the project.

Kaila Austin: It is an oral history and portrait project that I did in collaboration with the South East Neighborhood Development organization and I get to work in the community that raised me. I interviewed like ten to fifteen grassroots community leaders in the South East quadrant of Indianapolis, do their oral histories, paint their portraits and then connect them with the resources they need for the communities to stay stable in the face of the gentrification that's coming.

Kaity Radde: Kaila is a painter and an art historian. When she was attending Indiana University she got a Museum Study Certificate and focused on how people used space to tell stories particularly stories about African Americans. She worked in the museum field but she decided to leave because of the challenges of doing pro-black work there. Very quickly Kaila began to uncover immaculate black history collections in Norwood. It turns out that Norwood is one of the oldest stable free towns in the United States.

Kaila Austin: All the founders of these communities were the US Colored Troops. The only regiment of the US Colored Troops in Indiana is in Fountain Square which is less than a mile away. All of the founders of this community were US Colored Troops and at least ten to fifteen of their descendants still live in the original lots their grandparents built at the end of the Civil War. All of these families have full standing archives that date all the way back to emancipations. Some of them have their manumission papers, their lot sales documentation and family photo albums that date back to the Civil War. We are talking about really immaculate collections.

Kaity Radde: Kaila said almost known of which she has found appeared in State archives or in Indiana students text books. The first person Kaila talked to was a woman named Flinora Frasier who Kaila calls Miss Flynn. Miss Flynn is 92 and she keeps one of the Indiana's best black history archives in her garage. Miss Flynn made it her responsibility to keep the neighborhood's history safe. Her grandfather Sidney Pennick founded three AME churches in the late 1800s. All of them are still active today. When a member of the congregation has a major life event, Miss Flynn records it. When someone dies, Miss Flynn's there to preserve any historical documents they had from Civil War medals to family photos. She tried to get historical designations for her grandfather's church. She was told it wasn't significant enough to be considered, so she was skeptical of Kaila at first. The President of the Norwood Neighborhood Association convinced her to give Kaila a chance.

Kaila Austin: I was connected to Miss Flinora Frasier and she, when I first called her, she said, "Oh, another historian." She did not want to speak to me at all. The President of the Neighborhood Association had convinced her to speak to me and she said, "Fine, I'll talk to you." But she was not happy about it. Miss Flinora, we found out after, has historically been denied over and over again by the historical organizations in Indiana. She tried to get a historic marker for her grandfather's church when it turned 110 years old and they said that her grandfather's property wasn't significant enough. We have repeating records of them doing a disservice historically and she was not excited to talk to me at all when I called her on the phone. She was not happy about me coming in there and doing this. Then, as I got to know her more and the history of the community more, it's like, "Oh, that makes sense. You're expecting me to betray you." I went to pick her up at her house and I don't think she had ever met a black historian before, because her total demeanor changed.

Kaity Radde: In the beginning Miss Flynn seemed surprised that the things she had kept had historical value, like a picture she had of soldiers from Norwood getting ready to go and fight in World War II. Here is her and Kaila talking about it in the Memory Keeper's interview Kaila did with her.

Miss Flynn: This was one of the guy's things they had but they were the older guys, older than I am.

Kaila Austin: So when they are going to World War II?

Miss Flynn: Yes.

Kaila Austin: Yes there. I mean that's like a great piece of history to keep recorded. That's something you see in a history museum.

Miss Flynn: Oh, really?

Kaila Austin: Yes. That's something that if it's not kept the memory is lost.

Miss Flynn: I wrote the date at the bottom.

Kaity Radde: Eventually Kaila helped Miss Flynn find out more about her grandfather's earlier life and history. She found her grandpa on a slave census and then she found his grave when she had been right in the neighborhood all along.

Kaila Austin: Sidney Pennick ran away at emancipation and joined the Union Army in Louisville at 13 years old and fought in the Civil War. He saved his mother from enslavement because she was still there and later went to Indiana with his mother and started this community which is still standing.

Kaity Radde: In 1870 when Sidney and the original settlers were establishing Norwood the village consisted of about 20 black households. Norwood's first school was established in 1872, less than a year after Indiana legalized public education for black students. Pulling it off that fast showed that it was an incredibly organized tight knit community and very soon black politicians were making campaigns stops there. Three decades later at the turn of the century, Norwood had a 1,000 black residents living in an unincorporated village. They made decisions in a town council that operated by consensus.

Kaila Austin: This is our Black Wall Street. This is our Tulsa, Oklahoma. This is an affluent free black community that built itself up from scratch.

Kaity Radde: Ada Harris was the long time Principal of Norwood School and she was responsible for it's early growth and success. She bought a plot of land and old dairy barn to use as a community gathering space in 1908 and she owned other land along Madeira Street. When the city of Indianapolis annexed Norwood in 1912, city officials decided that Harris wasn't educated enough to teach in Norwood any longer. She went to get a degree at Butler University but even with that education she was never allowed to teach in Norwood again.

Kaity Radde: In her will she left her assets to the City Parks Department to build Norwood a community center.

Female from City Parks Department: Ada Harris runs the Community Land Trust for the neighborhood. She is the most educated member of Norwood. She has graduated high school, she is the Principal, she talks to lawyers, she deals with the city and she does all of the stuff because she knows how to do it. Essentially they penny party. A penny party is a rant party where somebody performs, everybody puts 25 cents in the bucket and once they get to $50 they buy another lot. Everybody owns everything together. Ada Harris specifically owns these properties on Madeira Street where the black library, the kindergarten class is, the community center and the park are. The deal is that Ada Harris is leaving these four lots, all of her liquid assets, and all of her material possessions, to the Indianapolis Parks Department under the agreement that they are going to build the Ada B. Harris Center for the Benefit of Negro Children in Norwood.

Female from City Parks Department: Ada Harris dies two years later, the Parks Commission sent their lawyer out to Norwood and the lawyer reports back and says, "It is neither needed nor necessary for the there to be a center for the Benefit of Negro children in Norwood." They auctioned everything off. They sold everything. They sold their library, their park, their community center and their kindergarten classes and the next year they bulldozed all of the buildings down. There is nothing left of the community that they built for the last 40 years. And the city, 110 years later, is repeating the same exact way that they treated us.

Kaity Radde: In the 1920s and beyond, Norwood was surrounded by notoriously racist neighborhoods. A clan distribution map from around that time showed about 250,000 clansmen in Indianapolis when Miss Flynn was a kid.

Kaila Austin: I mean it's unbelievable and so I am asking Miss Flenora, "What was that like? You're a little kid. The clan is like posted along the borders of your neighborhood. This is the only world you've every known. What are you feeling, because I would be terrified? I would be genuinely really scared." She said, "Kaila, I never even knew they were out there." I've never been anything but safe in Norwood.

Kaity Radde: That came up again and again in talking to Kaila, and then listening to the Memory Keepers interviews. Despite all the racist barriers stacked against Norwood, everyone took care of each other and the community continued to survive. In the Memory Keepers recording, Miss Flynn remembers her elementary school family including how her teachers subverted the State's curriculum to teach her and her class mates black authors and black history.

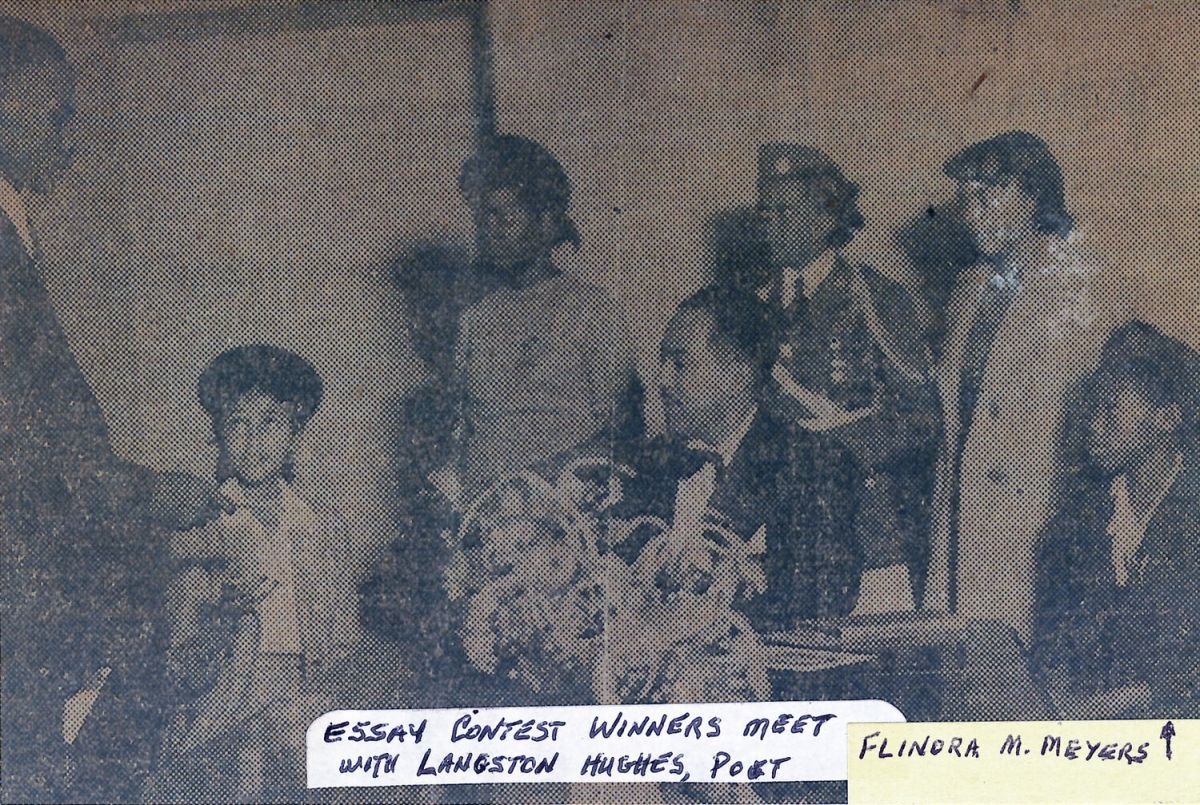

Miss Flynn: You know how we they have kids writing compositions? Well, I won, one time at school and I got to meet Langston Hughes and it must have been in the forties.

Kaila Austin: Had you read Langston Hughes? Had you read his work at that point?

Miss Flynn: We were a black school, and we studied about black people. Teachers managed to squeeze it in somehow. We had some smart teachers.

Kaity Radde: But then, when the school started busing and she attended an integrated school outside Norwood, she found that school became less interesting and less fair. On aptitude tests black kids like her didn't have the same base of common knowledge that white kids did.

Miss Flynn: The first time I've ever been in an integrated school, aptitude I guess they called it, I said it's so unfair, because black kids didn't know a lot of the stuff that was on the test. What did we know about concrete? The sidewalk was the ashes from the stove. We didn't know about sidewalks. How could you answer a question like this for example? Because we didn't have access to this stuff.

Kaity Radde: After annexation, the city of Indianapolis was slow to provide services. Norwood didn't get paved roads until the 1970s which is what Miss Flynn means when she says she didn't know about sidewalks. Norwood also didn't get electricity until the 1930s or plumbing until the 1950s, well after the white parts of the city. What Miss Flynn is saying here is that the lack of basic municipal services wasn't just a material problem. When she started attending school with white kids, it also meant a difference in what was considered common and valuable knowledge. Since the common knowledge among white people created the basis for schooling and testing, black kids weren't tested fairly which contributed to the racist idea that black people weren't smart.

Miss Flynn: Automatically some people thought we were dumb. We weren't dumb. We just didn't know. We hadn't the resource, because black people are smart, very smart. Should have brought you all thatlist of the inventions we've done. [LAUGHS] But we are always smart enough to find a way to not work hard; we didn't mind working but it was ridiculous to work hard when there was an easier way.

Kaity Radde: That's been the story of Norwood since the city annexed it. The white establishment imposed its will on Norwood and made things worse for the people there. They then blamed the poverty and disrepair on the people it was battering down. The people of Norwood have survived all this time but the pattern persists.

Female person from Norwood: The line between past and present is so thin.

Kaity Radde: The preservation in sharing of history is crucial but so is the immediate political reality of gentrification and structural racism. That's why the Memory Keeper's Project connects people to resources in addition to recording their stories.

Female from Memory Keeper's Project: How do we filter resources in a community in a way that uplifts what is already there. Instead of continuing this manifestos, the mentality of wipe everything out and start over? Because that is what is happening all over Indianapolis is that we are just wiping out black communities and building new ones on top of them. How do we create a structure that can work to preserve as it builds? How do we integrate historic preservation into urban renewal so that we're not losing these histories that these communities have taken 200 years to build? There is the Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs; if they are not safe and don't have access to food then they can't care about history.

Kaity Radde: Bringing up gentrification in the middle of talking about a local history project might seem random, but the way we remember history is more than an academic exercise. It tells us what to value about ourselves and about our communities.

Kaity Radde: Sampson Livingston, a friend of Kaila's gives historical walking tours called Walk and Talks. He is passionate about showing people the multi-cultural history of Indiana neighborhoods, especially if they think their neighborhood is and always has been white. He wants them to have a good time while he does it.

Sampson Livingston: I just wanted to look for myself where I was. I tell people to try to be where their feet are. So when you're doing that, you're obviously going to like history because you're like, wait, who was here before me?

Kaity Radde: I met him at the corner of McCarty Street and Virginia Avenue in Fountain Square where there is a historical marker for the 28th Regiment of the US Colored Troops. It's right by the interstate. As with most interstates, building it meant bulldozing homes and breaking up a predominantly black neighborhood.

Sampson Livingston: Over here we have the history marker for the Colored Regiment. This is Indiana's only black colored troops that fought in the Civil War and their camp was located right around here.

Kaity Radde: Right now, Sampson is developing a Fountain Square walking tour that will include Norwood, which is less than a mile away. But, as much as Sampson loves Indianapolis black history, even he didn't know anything about Norwood until Kaila looped him in.

Sampson Livingston: Without Kaila's information I would have completely left out Norwood like the city of Indianapolis has done time after time after time just because people aren't talking about it. The importance of talking about neighborhoods, talking about history, that's how it gets remembered and, when you only go to search Norwood a 100 later, what do you see? What do you find? I think it is cool that Kaila is getting these historians together, building an archive so that when a kid 50, 60, 70 years from now searches Norwood and lives in Norwood, they will see their neighborhood and see, wow look how strong we were and we come from a long linear of soldiers.

Kaity Radde: One of this favorite tours that he's given was for the Westfield Black Student Union.

Sampson Livingston: I went to a High School and I came on a walking tour, I was like, man that's so cool that they got to do this in High School because I would have loved to do this in High School to highlight the history that we have in Indianapolis that looks like me, that looks like them. The teacher, I wouldn't say he was shocked, but he was making jokes about how engaged some of the students were, as opposed to maybe how they maybe in school. They were having fun. They were taking pictures on the canal. They were having a good time, and it looked like they were excited to see themselves in Indianapolis.

Female Student: I don't know how to explain the impact of wanting to accomplish something great and never seeing anyone that looks like you who could have ever have done it. That's really harmful, and I don't really want another generation to have to grow up without knowing how much potential they have.

Kaity Radde: The city dismissing Norwood's history isn't just a disservice to its full story. It reveals which facts the people in charge of cultivating our historical memories find important. It helps racist officials make the argument that there is nothing of value in a place like Norwood. That it can delay providing basic services like running water and electricity. It guides official's choices about which neighborhoods to break up with interstate construction and which ones to leave in tact, and that, in turn, effects how people see the worth of themselves and their communities. Kaila said one of the most rewarding parts of the work has been seeing people get excited about themselves and rediscover some of their own self-worth. One of the clearest moments in her memory was at Miss Flynn's house when Miss Flynn met Kaila's father.

Kaila Austin: And she goes, "You know what? Your daughter keeps telling me that this is a free town and you know what, she's right. I've always been free here." And I was like, "Damn it's working." She hated me when I walked in the door the first time I met and she feels proud of herself today. I made that little black lady cry for good reasons at least once a week. It's like a great feeling because I'm sure she's cried a lot for bad reasons.

Kaity Radde: Outside of Norwood, it's story was of urban blight or didn't exist at all. The real story of Norwood is one of profound freedom and community resiliency but also disenfranchisement and racism at the hands of the surrounding white communities.

Kaila Austin: They are getting to know how important it is that they're still there. Your great-grandparents fought hard. They survived slavery and a war to come here and build a home for you and you're still here. You've got to fight for it. They fought for you.

Kaity Radde: Kaila said today Miss Flynn's archive is in the final stages of being designated as a part of the National Park Services African American Civil Rights Network. They are hoping to have a marker for her grandfather's church by the end of the year. It matters that Norwood is still here, still inhabited by the direct descendants of emancipated people. Burying history buries that fact. Unearthing it allows us to remember where we come from, good and bad, and to build a better future.

Alex Chambers: Kaity Radde produced those stories as an intern at Inner States. She is now an NPR NewsApps and NewsHub intern. All right, time for a break. When we come back we have a drawing lesson from a young person.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. Comic Artist Lynda Barry says, when we're kids we just draw, we don't need a reason. But most of us lose that capacity as adults. Why is that? Producer Kayte Young decided to consult an expert.

Kayte Young: I know someone who makes comics.

Beatrice: Beatrice [PHONETIC: Zora Nikki].

Kayte Young: She goes by Bea.

Beatrice: I am eight years old. I am in third grade.

Kayte Young: I heard about her work from her mom who is a dear friend of mine. I was honestly blown away by her technique and her story telling. I make comics too sometimes, but I came to it rather late in life and it doesn't come easy. Often my drawings get a bit overworked. I don't always no where to stop with the details.

Kayte Young: Bea's stories have that quality of aliveness that comic book author and Professor Lynda Barry talks about, and it seems like she knows some other tricks that comic artists employ, like how to depict motion and mood with an economy of line. If it sounds like I'm getting too high brow in my discussion of an eight year old's drawings that's because you haven't seen Bea's work.

Kayte Young: I invited Bea to sit down with me for an interview and to show me some of her comics. I started by asking why she likes to make comics.

Beatrice: You can draw and make whatever you want. You can draw an eyeball if you want, or something. Even something as like plain as a table. I like drawing different things.

Kayte Young: I asked if she has a story in mind before she starts?

Beatrice: No, I just make something up in my mind, write it down and draw it on a piece of paper and then staple it together to make it into a book. Sometimes my books don't really have writing in them; it's like a picture book.

Kayte Young: Picture books are best read allowed.

Beatrice: This is one is called Good Luck and Bad Luck. Good Luck going to the ice cream store, getting ice-cream. Bad Luck, falling down the stairs. Eeeee! Good Luck getting a present. Bad Luck getting an F in class. The end.

Kayte Young: I reminded Bea that our conversation was for radio and I asked if she could describe the pictures.

Beatrice: Going to the ice-cream store thing looks like there's an ice cream truck and then a person is getting an ice cream thing in the background and then you are just like licking your ice cream that you got. The falling down the stairs thing is basically just you bouncing down stairs.

Kayte Young: And then coming from the person use the word Eeee!

Beatrice: Eeeee! Getting an F in class is like a person sitting at a desk and looking at a sheet of paper and seeing that they got an F and the teacher is mad at them because they didn't do a very good job.

Kayte Young: How can you tell in that picture that the teacher is mad?

Beatrice: Because there's a cloud over their head.

Kayte Young: And then, she's got her hands on her head. And then, maybe, eyebrows are down on there too.

Beatrice: And then the kid surprised because he tried his best and apparently he got an F.

Kayte Young: She has this series of books where a word or an object is depicted in many different iterations. For instance, the book of No, where the word no is expressed in several ways or the Headphones book showing headphones in various contexts.

Beatrice: Sometimes I write a letter and try to think what I could do with it. I write a "2" or a "d" or something and like to try to find out how I could make a thing out of it, like a human or something.

Kayte Young: I asked Bea if she is ever the subject of her own books?

Beatrice: I have one where I make a book called The Book and it's basically about me getting the book that I actually made getting published, and it ending up in the library. I send it to a publisher and then the publisher gives it to a librarian and it ends up in a library, and my dad ends up checking it out.

Kayte Young: You can see Bea has a post-modern sensibility. Bea started making her books when she was doing a school on-line in 2020. They were writing assignments.

Beatrice: I liked it even though it was part of school.

Kayte Young: I know that Bea reads a lot of comics herself. I notice some Calvin and Hobbes collections in the room where we were talking. She sees her work as comics too.

Beatrice: Yes, but they don't have ten-year-old panels or anything, but they're justfull page pictures.

Kayte Young: Yes, but they do have the speech bubbles and some of the things like a little cloud over the teacher's head. It does seem like comic things where they're trying to tell you an emotion with a little symbol. How do you feel when you draw? Does it make you feel a certain way?

Beatrice: It makes me happy when I draw.

Kayte Young: Yeah?

Beatrice: Yes, mostly.

Kayte Young: Do you ever draw if you were like upset or something?

Beatrice: Sometimes I scribble on a piece of paper when I'm mad.

Kayte Young: Bea said she wrote a story called The Mad Penny one day when she was upset though she couldn't even remember what she was mad about. To make art you've got to have materials. Bea doesn't need anything fancy.

Beatrice: Usually I use crayons or a pencil.

Kayte Young: With any creative endeavor it can take a few tries before you land on a process that works for you.

Beatrice: My first book that I made I basically did it this way. I draw the picture, write it down and then I stapled it but I thought it was in the right order, but apparently it wasn't.

Kayte Young: Oh no, revision time.

Beatrice: We had these stapler things that can take out staples which my dad helped me with. I had to put the sheets in the right order and from then on I stapled it altogether and then drew it.

Kayte Young: Lesson learned. I wonder how it's changed her story telling to have the number of pages already decided before she starts. Sometimes the best art comes from constraints. Now, what about audience?

Kayte Young: Who reads your books?

Beatrice: Mostly my mom and my dad, whoever is home and not at work.

Kayte Young: And to expand these audience here are a couple of her stories for you to listen to.

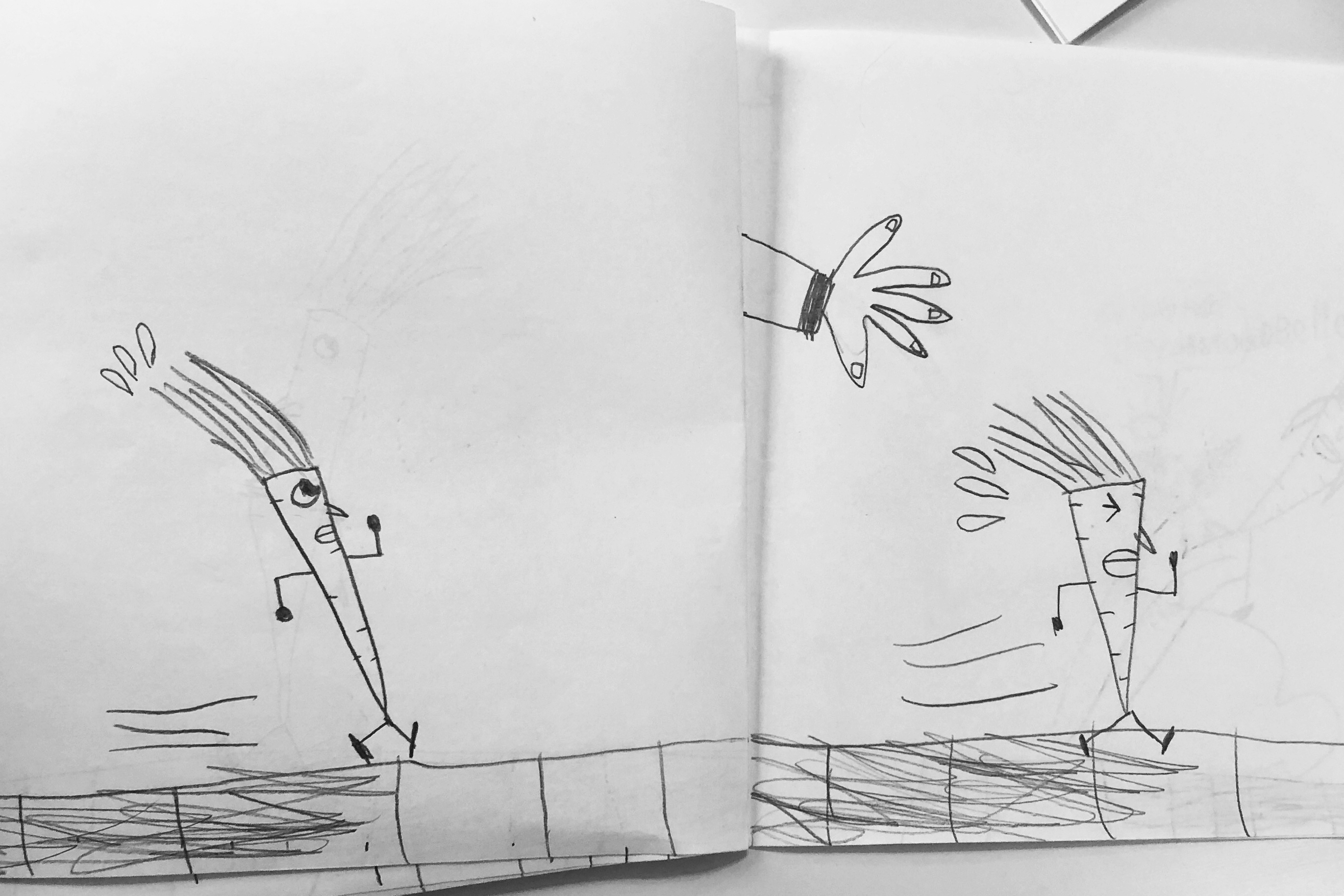

Beatrice: How about this one: a horror story about a carrot,and there's a carrot that is saying, "Oh no, I don't want to be in this horror story."

Kayte Young: Is it thinking it, though?

Beatrice: Yes. Ice cream! One day, he sees an ice cream store and he's like, "Yum!". "Yum indeed." And then he gets really full and he's like "urrr" and then he sees something and then he justs runs. If you can see, there's kind of like a shadow over him and the shadow grows and grows. There is a gigantic candy running. Then he gets pulled back but you don't see what pulled him back. One second later he's in a vegetable heaven. One of his friends, a potato says to him, "I had the feeling you'd be here soon." The end. Smiley face, smiley face. [LAUGHS]

Kayte Young: You see the hand in one reaching for him, he's running.

Beatrice: And then he's just [PANTS]

Kayte Young: Okay, so you're showing the movement in a lot of ways here. It's through the arms and legs, also through the lines, also the hair blowing back which is really his stance. It's like the wind and his eyes.

Beatrice: He's like arrrrrrr, hope he doesn't grab me, don't grab me. And then it grabs him. [LAUGHS]

Kayte Young: What I like too is that you don't really see the horror, which is the carrot getting eaten. You just see one second later.

Beatrice: It's like one second later, he's in vegetable heaven up in a cloud. [LAUGHS]

Kayte Young: And, one more story. This one is inspired by the 1985 book Imogene's Antlers, by David Small.

Beatrice: Bea's Antlers by Bea. One day Bea woke up with antlers. Getting dressed was frustrating because there's like an erased picture of a lamp. The lamp from her dresser is actually like on her antlers.

Kayte Young: So, is the erased lamp a part of that?

Beatrice: Bea came downstairs and Bea's mom fainted. It's like arrrrh! Bea tried to ignore the antlers, but It was no use because she was pulling really, really down in front and she accidentally took a picture of herself and she looked at her picture of the antlers. In this picture I forgot to take a picture of the antlers.

Kayte Young: You mean, you forgot to draw in the antlers?

Beatrice: Yeah. The next day the antlers were gone. Bea's mom was happy. Look. Until, the next day, she had a lion tail. The end. Here's a picture of a person with a microphone saying, "The End." And then they're saying, "I said, The End. You can go now."

Kayte Young: Bea says she's not making story books for school anymore but she is still drawing. As for what she's drawing? Well, that depends.

Beatrice: I get into something and I'm like, no I don't like that thing anymore and I go onto a new thing and I'm going to draw this. For instance, I like pigs, now I like cats and stuff like that.

Kayte Young: Yes. And right now, you're only drawing cats?

Beatrice: Yeah.

Kayte Young: You can see some of Bea's comics for yourself on our website wfiu.org.

Kayte Young: Well thanks again.

Beatrice: You're welcome.

Kayte Young: I've been speaking with Beatrice Nikki. She's a third grader at Templeton Elementary in Bloomington, Indiana. For WFIU Arts, I'm Kayte Young.

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or you've got some sound we should hear let us know at WFIU.org/innerstates. Speaking of found sound we've got your quick moment of Slow Radio coming up but first, the Credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me Alex Chambers with support from Eoban Binder, Aaron Cain, Mark Chilla, Michael Pakash Payton Whaley and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey. Special thanks to Memory Keepers a project of South East Neighborhood Development in Indianapolis. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists a Universal Music Production and Airport People. Alright time for some Found Sound.