Ellen Jacquart: There used to be huge ash trees here, and 25 years ago, they were still standing, but they were all dead due to the emerald ash borer. Slowly, those giants toppled and made big holes in the canopy, so we've got an uneven aged forest now, because we lost so many of those large trees.

Alex Chambers: That's botanist, Ellen Jacquart, remembering the ash trees of yesteryear, which is also this year, because she's talking from the future on how to survive the future. A show I made a while back, about how the world might feel in ten or 25 years.

Alex Chambers: This week Ellen and I take a walk in the year 2045, then I talk with the director of a new documentary about a leading athlete of the early 20th Century. He was a black track cyclist and a superstar. All that and more, after this.

Alex Chambers: Hey, it's Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers. Spring feels like it's around the corner, especially with this warm weather we've been having. It seems like it just keeps getting warmer. So, we're going to head when a time when it's even warmer than it is now with an episode of How to survive the future. Botanist, Ellen Jacquart and I took a walk in McCormick's Creek State Park in the year 2045. It was hot but the woods made it feel a little cooler. Here's our walk.

Alex Chambers: Hello.

Ellen Jacquart: Hi.

Alex Chambers: I think walking and talking will be good and then maybe at some point we'll sit quietly and talk a bit.

Ellen Jacquart: Okay.

Alex Chambers: If you're open to that?

Ellen Jacquart: I am. I have until 11:30.

Alex Chambers: That's totally fine.

Ellen Jacquart: Alright.

Ellen Jacquart: Oh, that's a pretty one.

Alex Chambers: What's that?

Ellen Jacquart: Appendaged water leaf or great water leaf, because it's the greatest water leaf. It really is. There are several other species, but smaller flowers, blah kind of looking, frankly. This is just a gorgeous one. Look at those flowers!

Alex Chambers: Wow, yes, that sort of lavender.

Ellen Jacquart: It's exuberant, so many buds and flowers on one plant and that's a really small plant. A big plant can be 2 ft around with just dozens and dozens of flowers hanging on it. There's one surviving in the midst of the nettles.

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Ellen Jacquart: Good luck, buddy.

Ellen Jacquart: Botanists are so used to this phenological calendar that we know when things are going to be flowering. When we see things that are flowering a full month earlier than they used to, it's hard not to see that and realize that has implications. I mean, we all love seeing flowers, so seeing them earlier in the year, that's great, but they're supposed to have pollinators and the insects that are pollinating them are not necessarily following the same schedule that the plants are. The plants are tuned into day length and temperature and insects may have a different calendar. If we've got plants flowering and the pollinators aren't out yet that's a big problem.

Ellen Jacquart: When I started working for the Nature Conservancy, I took a trip up to near Michigan City, Indiana, where we had a beautiful fen called Trail Creek Fen. I went up with the steward that handled that site and we walked happily through the fen in our rubber boots because it was mucky. There was skunk cabbage, marsh marigold and all kinds of stuff there. Then I got to this part of the fen and there was this huge shrub, it was about 8 ft tall and about 8 ft wide. It was massive, and I thought 'I do not know what this thing is.'

Ellen Jacquart: I started looking in guides and nothing, there were no flowers to look at at that point and I could not figure out what it was. Then I looked around the base of it and I saw hundreds and hundreds of little shrublings that were clearly the same species as whatever this was. I realized 'oh, no, this has got to be something non native and it must be invasive because look at all of this.' Finally, we put together all the clues we could, we looked in the guide and we came out to it was privet. It really struck at my heart because this was a fen that had lady slipper orchids. It had all this stuff, and as those little privet shrubs were going to grow, they were going to completely shade that stuff out.

Ellen Jacquart: What really made the biggest impression on me, as I was kind of stomping out of the fen, back to the truck thinking about how much time and energy it was going to take the steward to cut out that big one and then deal with the smaller ones, I finally raised my eyes and I looked at the neighbor. The neighboring property was a house about 100 yards away and they had a hedge that was 8 ft tall privet, all around the house.

Ellen Jacquart: For the first time it was truly clear how landscaping with invasive plants was really decimating our nature preserve. I haven't been back there in years but I'm wondering what it looks like now because it's not an easy thing to engage with a neighbor and convince them to get rid of a very large hedge. I was afraid that the future was not bright for that fen.

Ellen Jacquart: I am Ellen Jacquart, I am a retired Ecologist and spend my time hiking and looking at wild flowers and doing native landscaping in my yard.

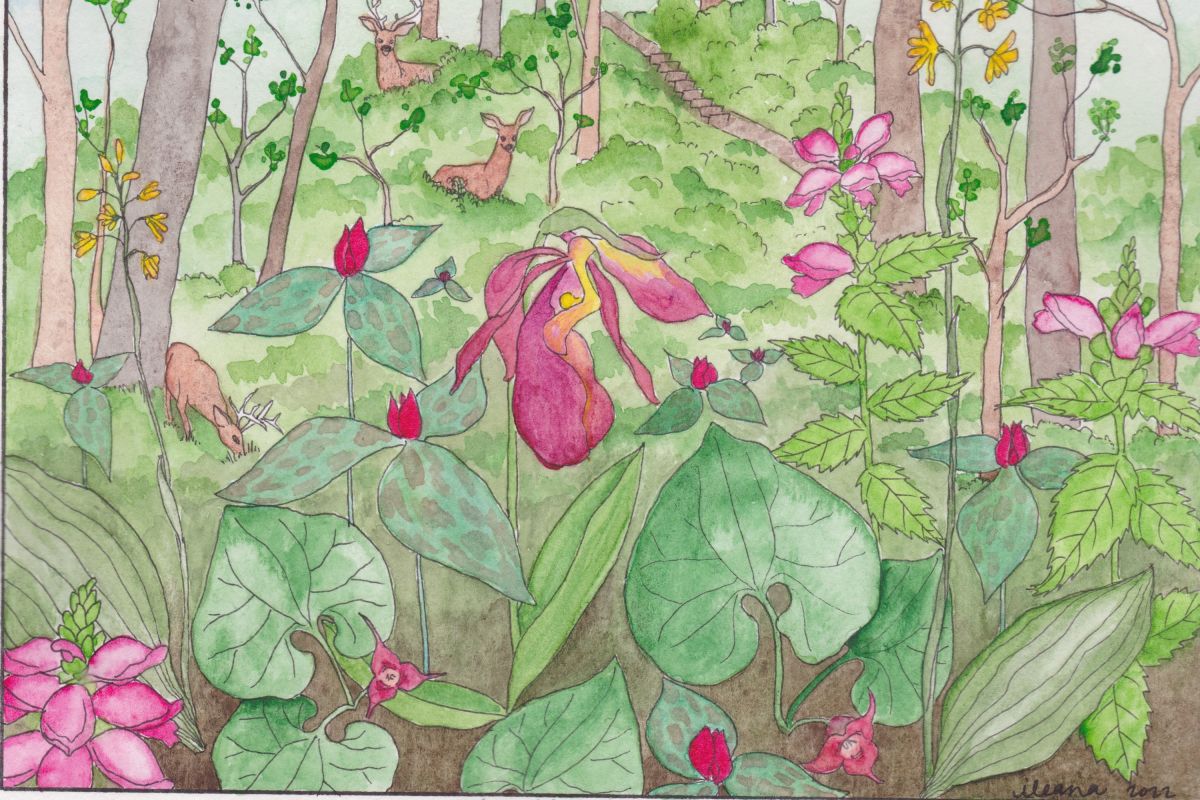

Ellen Jacquart: We are in McCormick's Creek State Park. It is late spring, kind of late May, where a lot of the early spring wild flowers have started to fade but the late spring wild flowers are in full glorious bloom.

Alex Chambers: How long have you been coming to McCormick's Creek?

Ellen Jacquart: Just about 50 years. It's a long time.

Alex Chambers: Has it changed?

Ellen Jacquart: Well, probably the biggest change that I notice is when I walk through 50 years ago there were little dirt pads, those were the trails. Then about 30 years ago they decided, no, these need to be bigger trails to accommodate the increasing people that were coming to enjoy the park. It turned into gravel trails that were 10 ft wide. Then more people came and the gravel wasn't holding up well so they decided that they needed to make them wider and asphalt. Now, much of the park, what used to be small trails, it kind of looks like county roads going through them, without the dashed line in the middle. The trails have gotten bigger, which has kind of broken up the forest even more, and there's still a problem with the deer population.

Ellen Jacquart: The trails have gotten bigger, which has kind of broken up the forest even more, and there's still a problem with the deer population. The deer had been identified as a problem at McCormick's Creek State Park 40 years ago and they've tried to reduce the population, but it hasn't been as successful as it should be. We find that a lot of the most palatable species, the things that deer want to eat, kind of disappear and we get more and more nettles. We're going to see a lot of nettles.

Alex Chambers: What are some of the ones that have been eating?

Ellen Jacquart: Oh, the trilliums, they love the trilliums. The orchids, the showy orchis is a nice late spring flower, and it's really unlikely we're going to see one today because deer just love orchids. Those are pretty much gone. The ones that hang on are like the guyandotte beauty because it's a mint and it tastes funny. The deer don't tend to eat it as much, so that we still have.

Ellen Jacquart: Another change we've seen is there used to be huge ash trees here, and 25 years ago they were still standing but they were all dead due to the emerald ash borer. Slowly, those giants toppled and made big holes in the canopy, new species came up. Not as many oaks as were in the canopy before because these small light gaps don't really help oak species that much, so we've got an uneven aged forest now because we lost so many of those large trees. There's lots of little patches of young trees filling in behind the ash that all died.

Alex Chambers: Did the ashes die in the twenty teens was it?

Ellen Jacquart: Yes. Emerald ash borer first came in 2001 in Michigan, 2005 in Indiana I believe, and really the first ash deaths in this area of McCormick's Creek, it was probably 2015 or so. Then they slowly died one by one.

Alex Chambers: I see. Shall we go down here? Okay great.

Alex Chambers: Did people just realize with the ash borer that it was just inevitable?

Ellen Jacquart: Yes. In the early years there was a sense of somehow we would keep it from moving outside of Detroit where it came in. They set up what they called 'fire breaks' where they would go in and on a very large scale remove all ash trees for a mile wide. This was in Northern Indiana to try and keep it from coming in and that did not work. It came in and slowly spread through the state moving to the south, and now it's pretty well established and we've got very few ash trees left. There's one species called blue ash and there's some of that in this park and it doesn't seem as susceptible to emerald ash borer. So, there's still blue ash but the white ash, the green ash, black ash and pumpkin ash pretty much all died.

Ellen Jacquart: McCormick's Creek State Park is a big state park and the first state park created in Indiana. It's known for having just spectacular plants, native plants and in the spring wild flower displays, in particular. I remember being there when I was younger and just being blown away by the number of species and then just the sheer display; the swaths, the hoards of native plants.

Ellen Jacquart: There's a place you can go, where I used to go, there were a couple of big old logs, sycamores that had come down and just kind of criss-crossed in this low area, which was right next to the stream that flows into McCormick's Creek. You'd get this creek-side location and all along the way you were seeing green dragon, Jack-in-the-pulpit, spring beauty, celandine poppy and all of the beautiful spring ephemerals. Later in the season, as those have just started to fade, the pink turtle head would come out. Until it's in flower you don't even notice that plant because it'sabout 1 ft tall, it's not huge, and the leaves are not real noticeable but then suddenly it comes into flower. It's called turtle head because the flower looks like a turtle head on end, like the mouth of the turtle is sticking up into the sky.

Ellen Jacquart: The common species is the cream colored turtle head, which is a nice little plant. But pink turtle head? You've got all these little pink turtle heads, and it's like a field of them as you're walking along the trail. Hundreds and hundreds of plants and a sight that you wouldn't see anywhere else in Indiana because it really is a pretty rare plant. Just an absolute abundance of it as you just walk through and look at those beautiful plants.

Alex Chambers: What were some of the shrubs and plants that did used to be here?

Alex Chambers: Well, there used to be nodding trillium. Lots and lots of nodding trillium. Prairie trillium, toad shade, those are also trillium species. Oh, this used to be a place for putty root orchid. There was putty root orchid everywhere, which is one of those strange winter orchids. We have a couple of orchids in Indiana that they put out their new leaf in late fall and it over winters, because plenty of sun is coming through because the trees don't have any leaves on. It's photosynthesizing all winter, then, come next May, it puts up the shoot of orchid flowers, about 1 ft tall. Then the flowers get pollinated, they produce their fruits and that leaf that was out all winter is shriveling up and dying so it really doesn't even have a leaf in the summer. Come fall, new leaf goes out. There was so much putty root in this state park. It's a really cool one.

Alex Chambers: Wow, I'd love to see that. So, trilliums, putty root. Oh, what's that?

Ellen Jacquart: You got it. That's putty root.

Alex Chambers: That's putty root.

Ellen Jacquart: I can't believe you did that.

Alex Chambers: Amazing.

Ellen Jacquart: In the midst of nettles, you can't grab it. I don't even see the leaf at the base it's completely dead, brown. Wait, there it is. There it is. That's the putty root leaf that was out all winter.

Alex Chambers: Familiar orchid leaf.

Ellen Jacquart: I was really looking for that, hoping we would see it. There it is, that's the putty root orchid, it's getting pollinated right now.

Alex Chambers: Oh, yes.

Ellen Jacquart: Then it will turn into little hanging fruit brown pods that have the seeds.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Ellen Jacquart: How fun! Yes. There are places where there is a lot today, but it can be hard to see, especially if it's just brown back there. It kind of blends in and you don't notice it given the color of those flowers, kind of a crimson dark brown/yellowish green.

Alex Chambers: Yes. I feel like it's a strange and unusual stock and flowers but the flowers themselves aren't particularly exciting.

Alex Chambers: No. You have to get up close and then look into them to see the complexity of an orchid flower.

Alex Chambers: Right. Yes, I can see that close up.

Alex Chambers: This is Inner States and we're listening to Ellen Jacquart on the podcast How to survive the future. We'll be right back.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. Welcome back. We're in the middle of McCormick's Creek State Park, with botanist Ellen Jacquart. It's about 25 years in the future. Let's get back into it.

Ellen Jacquart: So, when I was working 40, 50 years ago, the single biggest hazard that our workers had out in the field was ticks and tick related illnesses. As the years went by, we saw an incredible increase, not only in the number of ticks that we saw, and the range of the ticks. Because when I started my career lone star ticks were known from counties in Southern Indiana, near the Ohio River. The lone star ticks are now all over the Indiana Dunes National Park. So they have expanded their ranges.

Ellen Jacquart: The populations are higher, in part because the invasive shrubs have really dominated the under-story of a lot of our forest systems and when those shrubs make that dense thicket in the under-story, it provides cover for the small mammals, for the deer, who are the hosts for the ticks.

Ellen Jacquart: There were a couple of ground breaking studies back 50 years ago, that pointed out that, if you go in and you count the number of ticks in a forest, that has Asian bush honeysuckle in the under-story, and then you remove all the Asian bush honeysuckle and you go back and you count the ticks, there's a significant reduction in the number of ticks. What it means for people is that, the Public Health Office notes that there's a significant reduction in the tick-carried illnesses. And those include not just Lyme disease, which is pretty well known, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which has been a bad problem in Southern Indiana, but also ehrlichiosis, and some others that I can't even remember the names.

Ellen Jacquart: It seems like, about every five years or so, a new disease was identified that we didn't realize before that the field workers had had it, but nobody knew what it was. And then they would trace it and it would be traced to atick. And it would be a new tick carried illness.

Ellen Jacquart: As that threat spread and more and more people became aware of the health implication of invasives, they actually were able to pass more stringent regulations, so that plants that were going to be sold had to go through an assessment and shown to be non-invasive before they could be sold.

Ellen Jacquart: But it wasn't magic pixie dust that just made all the invasives already out there on the landscape disappear and they didn't disappear. They seemed to do better with climate change, the slightly higher CO2. The earlier growing season is something that invasive species can often adapt to, better than native plants.

Ellen Jacquart: And so, where we had invasions, they continued to spread unless the land owner or the public agency was willing to go in and control those invasives. And they had to make hard choices. I think in those years, agencies in particular, became a lot more strategic about, "We've got all of these acres, where do we have enough money to spend and be able to remove the invasives and protect the biodiversity that we have?".

Ellen Jacquart: In most public areas now, you'll see almost, what you might call sacrifice areas that have just grown up in Oriental Bitter Sweet and Asian bush honeysuckle, but where there was diversity, the nicest areas, they've drawn a line and that's where they focus their efforts, so that we still have some remnants that you can walk to and see whatthings looked like once upon a time before invasives really took over much of the landscape.

Unknown Female: Hi.

Ellen Jacquart: Hi.

Alex Chambers: Hi.

Ellen Jacquart: Having a good hike? [LAUGHS]

Children: No.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS]

Ellen Jacquart: And we're seeing some of the spring ephemorals that are now fading, like the Mayapple flowers. We've got the ferns that are coming out. Here's a nice fern. Look at this. Oh, I love this one. This is glade fern. It is just tall tufts of ferns and just simple pinnate on the frond. And it's a fern that really likes moist woods and that's what this is. And importantly, deer don't eat ferns, almost ever.

Ellen Jacquart: In ancient history, when Brown County State Park had such high deer populations, that the hills were actually brown. That was 1989 and it was my first year in Indiana and I could not believe, in the middle of summer, I was seeing these huge hills that were brown. The only green left was Christmas fern and a few other ferns that the deer refused to eat.

Ellen Jacquart: What was really most dramatic about Greens Bluff Nature Preserve, and what drew attention to it, and what got it protected by the Nature Conservancy back in the 1960s were are the hemlocks. There were these gorgeous remnant stands of hemlock, lining the bluffs. They were there because, when the glaciers were there, it was cool enough, it was wet enough, they established. As the glaciers receded, they held on in these little ridges and canyons where they were protected from the heat of the middle of the day. They were beautiful.

Ellen Jacquart: As the years went on they stopped reproducing so much. We just weren't seeing young hemlocks in the stand any more. We figured that that tied to climate change and that we were seeing mortality among some of the older hemlocks and maybe it's just too warm. It's too dry in late summer, due to the changes we were seeing in the climate, and that was not helping.

Ellen Jacquart: But the final nail in the coffin was, hemlock woolly adelgid. That's a little bug. Looks like a mealy bug that attacks hemlocks specifically, and we had been waiting for it to arrive in Indiana for decades. Hoping that it would stay away because we are hundreds of miles from the closest hemlock stand in Kentucky and we had hoped we were safe.

Ellen Jacquart: Unfortunately, it came in the way I was afraid it would. People are buying hemlocks for landscaping and they're coming from Tennessee and North Carolina, both of which are covered in hemlock woolly adelgid. And so some hemlock woolly adelgid came in one of those landscaping trees and then it moved out into Greens Bluff and about ten years ago, the last one pretty much died.

Alex Chambers: Do you remember the moment when you realized that it had come to Indiana?

Ellen Jacquart: Yes because I have been for many years. They send out reports from the Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology. I used to work with them as a partner and every time there's a new insect pest, they send out a report and I saw that report and my heart sank. I had tried for years to get that division to put an external quarantine on hemlock, meaning that we would not bring hemlock into the state because of that very risk.

Ellen Jacquart: We saw it twice in Michigan that it was landscaping hemlocks that brought hemlock woolly adelgid into Michigan, and now they're fighting it. But they didn't do a quarantine and those hemlocks kept coming in and it finally spelled the end of hemlock in Indiana.

Ellen Jacquart: That's unfortunate. Idiots. Let me just put you in here. Had a few roots on it and they're pretty good at re-rooting.

Alex Chambers: And what is that?

Ellen Jacquart: Wild ginger. I probably should have shown you. Wild ginger. That's the flower. And a fruit is being produced there. If it can re-root, maybe those seeds will finish ripening and be able to start more plants.

Ellen Jacquart: It's a real shallow rooted plant. I use it a lot in my landscaping because it makes a beautiful carpet of wild ginger. So that's a lot of my landscaping.

Alex Chambers: One thing I was thinking about was the pink turtlehead, right?

Ellen Jacquart: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: And having pretty much lost that in the recent decades, and how the first couple of decades of you being here, it was just this vast swath of amazing pink flowers. Not to sound callous but it's one kind of plant and it's one small spot. What does it matter, I guess?

Ellen Jacquart: Yes, I've had that question over the years. And I guess there are different ways of looking at it. If you're a spiritual person, these are an amazing plant species that have evolved over hundred of thousands of years and have this intricate relationship with the pollinators and the wildlife that eat the fruits. It's a part of a network. And by pulling out an individual species, it changes all of that connection.

Ellen Jacquart: It's just like a car. If you have a car and you pull off a windshield wiper, it will still drive just fine with just one wiper. But then if you take the steering wheel, that's a little difficult to make it go. As you remove one piece after another, it just gets harder and harder for the system to actually function. Ultimately, from a selfish perspective, these systems support us. These systems are what keep the human race going, by cleaning our water, by providing oxygen. All of these different things that nature is doing for us, and if we're basically tearing it apart to the point where it no longer functions, we are harming ourselves. There's a lot of uses beyond simply the fact that all living beings, I believe, have the right to survive.

Ellen Jacquart: All species have a right to survive. The evolution that created those species should be respected. Individuals are going to die but we start seeing whole populations blinking out, that's like the canary in the coal mine. You're seeing real impacts and reasons that that species can't survive. That should be a red flag to us. What about the human species? What's causing all of these extirpations of native plant species, and what does that mean for humans?

Ellen Jacquart: Here's the park office and back here, across the road, to trail two, you go down. There's a split off to see the old quarry, which is worth seeing, it's fun. A lot of history there. The limestone was loaded onto boats on the creek.

Alex Chambers: Oh wow.

Ellen Jacquart: But if you go straight, what I recall in this area, before you get close to the McCormick's Creek, if this is a low area with some down trees and it's just wet and mushy, that's where the pink turtlehead is. So that should be it, right there, unless I'm mis-remembering.

Alex Chambers: Oh, thanks.

Ellen Jacquart: I've got multiple maps. I always grab extra ones. Because sometimes you think, "Wait, does that trail connect to that trail if I do this?" I have extras.

Alex Chambers: Alright, bye Ellen.

Alex Chambers: That was episode three of How to Survive the Future. A show about today from an imagined tomorrow. I produced the show with Allison Quantz who also came up with the title. We had music by Airport People, Backward Collective and Last Ledges, and Ramón Monrás-Sender. How to Survive the Future was produced in partnership with Indiana Humanities with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and with further support from the Writers Guild at Bloomington.

Alex Chambers: You can listen to more episodes whereever you get your podcasts. Alright, it's time for a break. When we come back, poems about walking in the dark, time and memory. And then the most important cyclist you've probably never heard of. Stick around.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. We're back in the present, but what if memory could flow backward? Here's poet Shana Ritter.

Shana Ritter: Daylight savings time. The last two days I have risen to light. But for weeks before I stepped out into the barely dawn. The dogs big paws padding beside me as we walked the long gravel drive circling back to the pond's little shore. The last two nights I have stepped into shadow though it is still early evening, hours before real dark. The dog and I walk toward the field where the full moon, blue moon, grazes bare trees the way eyelashes might light on a cheek. As a child, if I found a stray lash, I'd place it on my fingertip to make a wish. Close my eyes, draw in my breath, blow. I don't remember the wishes but recall the way belief held in that weightless gesture. The way I trust my steps on the path I can't see, my dog beside me as the world falls past time. As if changing a clock changes anything at all.

Shana Ritter: Avenoir. The desire that memory could flow backward. And that definition comes from the dictionary of obscure sorrows. There is a woman who rows alone across the Atlantic day after day. She faces the water she left in order to pull toward the shore where she is going. On clear days she turns her head and twists her torso to look at a line where blue wavers into gray. She imagines herself arriving, but she must turn backwards if she is to go forward. On days when fog sets in and rain falls, she cannot see at all. She keeps on rowing, trusting her strong, callused hands. The tendons in her arms taking rest only briefly in the drift of current. She pulls and pulls, longing for the lip of shore, for the days she can look back on the ocean crossed alone.

Alex Chambers: Shana Ritter's poetry and short stories have appeared in various journals and magazines. Learn more at shana-ridder.com.

Alex Chambers: Okay, we turned the clock forward. Now let's turn it back a little more than a century.

Todd Gould: I think it's just so surprising when you go back through and you find all of these old magazines and newspapers from these French publications and he's on the cover of all of them and. Giant headlines and that kind of thing. So I don't think you really realize how powerfully important he was at that particular time and that he was able to carve out, not only space for himself, but also just for the African American and black population on a bigger scale. And I think he understood that right from the get go. Even as he was doing that he totally understood that.

Todd Gould: So that's where it's an extraordinary story right? He set all these world records and he did all this wonderful stuff and that's certainly fine, but it's not really a bicycling movie maybe as it is about race and society.

Alex Chambers: Before football was at the top of the American imagination, before basketball was creating stars, the US, and really the world, was obsessed with track cycling. That's where the stars were. And right at the turn of the 20th Century, the superstar was Major Taylor. Major Taylor got his start in Indianapolis. And a documentary about his life comes out this Monday, February 26th. It was produced right here at the WFIUWTIU offices by Time Gold. Todd recently made the track downstairs to the radio studios to talk with me about who Major Taylor was and how making a documentary is really less about the film and more about the community that results.

Alex Chambers: So, Major Taylor. He was born in 1878 in Indianapolis. His parents named him Marshall Walter Taylor.

Todd Gould: His father served in the US Color Troops during the Civil War and then they moved from Kentucky up to Indiana right before he was born to be able to have greater economic freedoms and social freedoms in Indiana that the family was not able to get in Kentucky.

Todd Gould: Then he, as a youngster, started working for a couple of different bicycle manufacturers in Indianapolis. This was before automobiles really came in to vogue when people didn't have automobiles. But bicycles were the fad, that was the trend at the turn of the 20th Century. And this gave him an opportunity, even as a young African American, to be able to carve out a place for himself and to give him some agency.

Alex Chambers: He wasn't just working at the bike shops, he was also riding. And one day a couple of promoters saw him in this race.

Todd Gould: Completely untrained, he was able to step in and be within two seconds of the world record for the one mile race. And so they said, "Hey, I think we can really do something with this kid and if we train him correctly and help him in some ways, he actually has a chance to be an amazingly talented athlete". This was a time also when track cycling was more popular than baseball, it was more popular than horse racing, it was more popular than boxing at the time. People that were in this particular sport were making more money than anybody else. So the top baseball players of the era would make $2,500 a year. Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson, these top baseball players would make $2,500 a year. Major Taylor, at the same time, was making over $50,000 a year, year after year after year. So it helps to show what this guy was able to do and the kind of talent that he had.

Todd Gould: He went to Canada to win the World Championship at that time and then was able to start racing all over the United States. He was racing all over Europe. He was a sensation at the time. As the only black face in the crowd, he stood out most certainly. But I think it was also something that intrigued fans of the sport and then launched him into this stratosphere of amazing athleticism and talent. He spoke three languages and he played the piano and the mandolin. He was really kind of a renaissance man at that particular time. And coming from a very humble background where he had no formal education and his father was a coachman. They helped take care of a wealthy white family's horses and so they would take him along. So this was something that was so incredibly unlikely that this would have happened. But because he created these opportunities for himself, even from a very young age, he was able to come through and they were able to have him come in and set these world records and set the world on fire with the excitement that surrounded this guy.

Todd Gould: And he was attracting 15-20,000 people to each event that he was coming to. So that was a big deal at the time and something that was very exciting for fans as well as other racers, promoters that wanted to have the Michael Jordan of track cycling to be able to step in with that high level of talent.

Alex Chambers: He was on the cover of magazines across Europe and he did product endorsements too.

Todd Gould: His roll, even as a spokesman, for them to hire a black face to come and promote bicycle parts or other things that he was helping to promote, they would say "We want this guy to help sell products and have these commercial endorsements". And that was at a time when that was not happening either. But Major Taylor was so good and so famous that people wanted him to be a part of that.

Alex Chambers: Because he'd been such a big deal and because so few people know about him today and because he was from Indianapolis, Todd decided to do a documentary about him.

Todd Gould: Yes.

Alex Chambers: And then you had to go and track down all the history.

Todd Gould: Right. So a lot of it is digging through the four or five really good biographies that have been written about Taylor. So I read those. He has his own autobiography so I read all of that/ and then you think, "Okay, how do we tell the story most effectively?". Sometimes it might be a sound bite from an Historian or Archivist or athletes and sports executives to talk specifically about the fact that because Major Taylor did this, that gave me an opportunity, 100 years later to be able to do these same kinds of things in the world of sports. So I think that that's exciting. So I was reading up about all of that and then also starting to dig through a lot of old photograph archives. There's no film footage of Major Taylor. News reel film didn't really exist at the time. Nor do we have any radio interviews or anything with him. But I do have a ton of photographs that I've been able to locate. And not just with a couple of archives here in the United States but giant archives in Paris and in Germany.

Alex Chambers: There were also a lot of photos in private collections. And finding those was a real treat for Todd because the professional archivists got excited and they could bring those photos into the public record by showing them the documentary.

Todd Gould: And then, make sure that this person who's the private collector is then linked with the archivists in these other places around the United States to make sure that they have connections to be able to use those in something later on as some sort of exhibit that they're maybe trying to do.

Alex Chambers: In some ways that's Todd's whole goal in making documentaries. It's almost not about the film itself but the connections he can help people make beyond the film.

Todd Gould: I find that stuff not only fascinating, but incredibly exciting for me as a film maker to be able to say, "Yes, let's pull all these groups together. Have you met so and so? Have you met so and so? Do you realize that this person has this thing?". One person might be in San Diego and somebody else is in Chicago and somebody else is in Boston and they say, " We had no idea". But now they're all talking to one another. The Congressional Gold Medal Act came about because I was connecting some people in Chicago with this museum in Massachusetts and people in Indianapolis. So I'm trying to get all these people to talk to one another and now we have this opportunity because of Congressman Jonathan Jackson's efforts in the House of Representatives.

Alex Chambers: And he is Jessie Jackson's son.

Todd Gould: So Jonathan Jackson is Jessie Jackson's son and the Godson of Martin Luther King Jr. And he is a Congressman from the first district of Illinois which is in Chicago. And he is wanting to promote this Congressional Gold Medal Act to try to get Congress to recognize Major Taylor, posthumously.

Alex Chambers: They interviewed Congressman Jackson for the film and Todd said that a lot of people came up to the Congressman after the interview to push for Major Taylor to get a Congressional Gold Medal. The Congressman said "Yes, he would introduce an Act to try to make that happen". And then...

Todd Gould: Two weeks later I tune in on YouTube and there he is on the floor of Congress reading that very Act and I thought to myself, "There we go". I think that, to the extent that we can help facilitate that as PBS and NPR storytellers, I think that that's the very best thing that we can do.

Alex Chambers: I actually really love that idea that the legacy of what comes about through the creation of this documentary is not the documentary itself but the conversations that happen.

Todd Gould: Yes.

Alex Chambers: All the people you bring together.

Todd Gould: Absolutely, Alex. That's exactly what it is. And so it's so fun and rewarding for me to see that kind of stuff happen,.

Alex Chambers: Major Taylor, Champion of the Race, premiers on WTIU and PBS video on Monday February 26th at 8pm.

Alex Chambers: Eric Rensberger is a local poet here in Bloomington. He self-publishes his books and sometimes Gorilla publishes his poems on public kiosks and lamp poles. I like the way these little prose poems take everyday life and make it a little stranger. I hope you do too.

Eric Rensberger: Reading. The article said the public figure said his intentions had been misrepresented by those saying negative things about him. I was reading in a hurry because I was fundamentally uninterested in the story but thought it was something I should want to know more about. Because I was speed reading, I read intentions as intestines. They misrepresented my intestines. This was so close to making sense that I paused and re-read the complaint about what was being said that was quoted in the article I was not really interested in. And I thought about what misrepresented intestines might look like. I took a sip of coffee realizing that my reading was no longer speedy and that it had been slowed down in order to contemplate not something hard to understand or beautiful to read, but an absurdity that both confused and stimulated the imagination. Why do I push myself to read so fast so early in the morning? I thought about my intentions.

Eric Rensberger: Historical imagination. They moved about in smaller rooms. We have proof of this. Awkward as it seems, they still manage to get from one room to another by edging around the stacks and piles. In the rooms where one would sit and talk, the furniture was so close together, knees touched but knees were smaller then. We have proof of this. Even if the seating was cramped, there was still room for a table with a small surface area to sit between, say, an armchair and a small couch or love seat. You could set a drink on it or an undersized sandwich. Perhaps even something you pulled out of your pocket because pockets were bigger then and we carried in them things that nowadays we would leave at home. We have proof of this. So out of the pocket come an antler inset with obsidian flakes along the outer edge. It could be laid across the knees where they touch. So much easier to stay here talking with each other than to get up and edge our way out. Edging not just the piles this time, but each other as well. But it might be worth it just get out of the rooms, pass through a final door and stand outside breathing. To be done with small rooms for once. We have proof of this.

Alex Chambers: Eric Rensberger. You can find more at ericrensbergerpoetry.net

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or if you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/innerstates. If you like the show you can review and rate us on the app or Spotify and tell a friend. Okay, got you a quick moment of slow radio coming up. But first, the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers. Avi Forest is our associate producer. Our social media master is Jillian Blackburn. We get support from Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is Eric Bolstridge. Special thanks this week to Ellen Jacquart, Todd Gould and LuAnn Johnson, producer of Poets Weave, for the poems. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Music in the Major Taylor story was made for the Major Taylor documentary by Tyron Cooper. Alright. Time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: That was banging icicles off the dormer window to prevent ice dams, recorded by Mary Craig. Thanks Mary. Until next week, I am Alex Chambers. Thanks, as always, for listening.