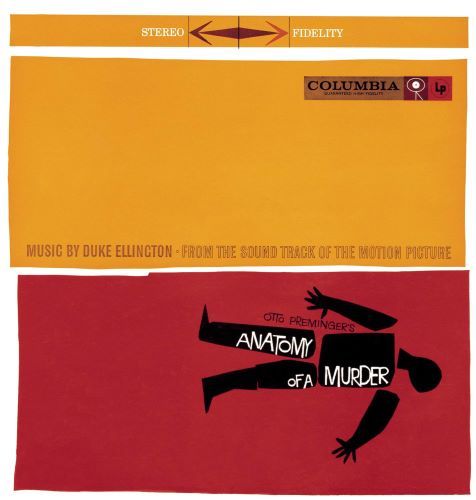

In 1959 Duke Ellington wrote the score for a major Hollywood film starring Jimmy Stewart.

The movie business emerged in early 20th century America as one of the nation’s most influential and popular forms of culture. Like nearly all forms of American culture, the major-studio system that produced most films was not generally a welcome place for Black artists, including the important job of writing and/or arranging the music that accompanied movies and served to provide emotional and narrative cues for the audience. Though jazz musician Benny Carter had worked on scores for the 1943 film Stormy Weather and several other Hollywood projects, Black composers remained almost completely absent from the studio scene in its early decades. From the 1960s on this began to change, with Quincy Jones, Herbie Hancock, Oliver Nelson, Isaac Hayes, and Terence Blanchard some of the notable figures who enjoyed success in the industry. In the first half of this program, I’ll focus on Duke Ellington’s score for Otto Preminger’s 1959 movie Anatomy Of A Murder, which starred Jimmy Stewart as an Upper Penisula Michigan attorney defending a soldier accused of murdering a man alleged to have raped the soldier’s wife, and George C. Scott as the prosecutor trying to convict him.

In 1959 Duke Ellington was still enjoying the professional and artistic rebirth that had begun in 1956 with his triumphant performance at the Newport Jazz Festival, and his score for Anatomy Of A Murder is now seen as a highlight of his post-Newport era. Writing about the score, Richard Domek says that "With its orchestration (massed ensemble sounds juxtaposed with chamber-like writing), formal design (blues, song form, 'formless' segments), thematic transformation serving as a means of musical growth, unity in the midst of compositional collaboration, advances in the handling of tonality, harmony, and dissonance, exploitation of the “suite” as a compositional form, adherence to the coloristic 'Ellington Effect,' and even in transmitting an indefinable 'essential expression of jazz,' Anatomy’s music affords a great comprehension of what Ellington, (Billy) Strayhorn, and the orchestra were about in a later and fruitful period for the band."

Otto Preminger was a successful, well-established director when Anatomy Of A Murder was made, with movies such as Laura and The Man With The Golden Arm, as well as the all-black films Carmen Jones and Porgy And Bess, to his credit. According to his wife, Preminger sought out Ellington’s services because he knew Ellington’s cultural stature would attract further attention to his new project.

Anatomy of a Murder was a provocative movie for its time, with overt references to sexual acts and behavior, mostly occurring in the film’s trial testimony scenes. Actress Lee Remick played Laura, the sensually alluring wife of the soldier being tried for murder, and was the inspiration for one of Ellington’s main themes for the movie, titled “Flirtibird.” (Singer Peggy Lee would soon add lyrics to “Flirtibird” and turn it into a song called “I’m Gonna Go Fishin,” that became a minor standard.) We’ll hear it as a vehicle for Johnny Hodges’ alto saxophone, followed by another Ellington composition, “Hero To Zero,” which features tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves in a ballad setting:

Ellington and his band had appeared in short films, most notably the 1935 Symphony In Black, as well as Hollywood studio productions such as Check And Double Check and Cabin In The Sky, but Anatomy Of A Murder was his first Hollywood soundtrack assignment. Writing for a film score instead of a recording or live performance was a different challenge for Ellington—he was composing music that would be used to accentuate the movie’s atmosphere and help drive its storyline. He later said that spending several weeks on location as Anatomy Of A Murder was being shot in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in May of 1959 helped him in this regard. He then went to Hollywood to continue working on the score, eventually joined by the rest of the Ellington orchestra, making for his longest stretch away from the band since its formation in the mid-1920s. Ellington and his musicians then took several days to record the soundtrack in Los Angeles. From it here’s “Midnight Indigo":

As was nearly always the case between 1940 and the mid-1960s, Ellington worked in collaboration with his writing and arranging partner Billy Strayhorn, who spent some time on the Michigan film location ahead of Ellington's arrival. Two of the recordings we just heard are singled out by Walter van de Leur in his authoritative Strayhorn book Something To Live For as bearing distinctive Strayhorn touches: "Although Ellington wrote the larger part of the recorded score of Anatomy Of A Murder, there is a striking Strayhornesque quality to pieces such as 'Hero to Zero,' 'Sunswept Sunday,' and 'Midnight Indigo.' In 'Hero To Zero,' for instance, the orchestral background to Paul Gonsalves' solo consists of consecutive entries by various instruments, an orchestral texture that resembles Strayhorn's technique of timbre melody."

In addition to writing music for the film’s score, Ellington also had a small on-screen part as Pie-Eye, a local jazz pianist and bandleader whom Jimmy Stewart’s jazz-loving character sits in with during a scene at a club. We’ll hear the Ellington small group from that scene, referred to as the P.I. Five, doing Ellington’s composition “Happy Anatomy,” preceded by the full Ellington band version that also appeared on the original soundtrack—Duke Ellington at the movies, on Night Lights:

Anatomy Of A Murder received seven Oscar nominations but got shut out at the 1960 awards ceremony, overpowered by William Wyler’s Ben Hur. Sadly, none of the film’s Oscar nominations were connected to Ellington’s score, but his music did win three in three different categories for that year’s Grammys. For some time it was viewed as a lesser entry in Ellington’s discography, but in the years leading up to its expanded 1999 reissue on CD, it was championed by musician Wynton Marsalis and critic Stanley Crouch, with Marsalis touting it as “the most mature sound of the Ellington band.” Writer Tom Piazza dubbed Ellington’s music for the film “the closest thing we have to a vernacular American symphony.” And it’s notable as Ellington’s first extensive work on a Hollywood production-- two years later he *would* receive an Academy Award nomination for his and Billy Strayhorn’s work on the Paul Newman-Sidney Poitier movie Paris Blues—and for being what Ebony Magazine celebrated as the first major American film score written by a Black composer. From the soundtrack, here’s Duke Ellington performing “Upper And Outest":

Duke Ellington performing “Upper And Outest” from the Ellington orchestra’s recording of his score for the 1959 movie Anatomy Of A Murder. Coming up in just a few moments, a convergence of Third Stream jazz and film noir with Modern Jazz Quartet pianist John Lewis’ score for the movie Odds Against Tomorrow.

Duke Ellington’s triple-Grammy win for Anatomy Of A Murder, which I highlighted in the first half of this program, may have overshadowed another superlative score done that same year for director Robert Wise’s noir film Odds Against Tomorrow, which prominently featured a score written by jazz pianist and Modern Jazz Quartet member John Lewis. Odds Against Tomorrow starred Harry Belafonte as a gambling-addict singer and Robert Ryan as a racist ex-con, who are recruited by a corrupt ex-cop to help rob a small-town bank. It was adapted as a screenplay by Abraham Polonsky, who had fallen victim to Hollywood’s 1950s blacklist of Communist and leftwing-affiliated writers and performers. Robert Wise had made a name for himself first as an Oscar-winning editor for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and then as a director of 1950s films such as The Day The Earth Stood Still and I Want To Live. His greatest successes, West Side Story and The Sound Of Music, were still to come.

John Lewis was not a stranger to writing film scores… he had previously composed music for the 1957 French film No Sun In Venice, but those had been isolated pieces, whereas Odds Against Tomorrow required more active integration with the film’s atmosphere and narrative. Polonsky’s screenplay called for “music in a modern, moody, sometimes progressive jazz vein, carrying an overtone of premonition, of tragedy—of people in trouble and doomed. The music will be a continuing and highly expressive voice in the story.” Working with early clips from the film as it was being shot, Lewis composed 21 cues for the soundtrack. Here are some excerpts from his score:

The score was recorded by a 22-piece ensemble that included Lewis’ Modern Jazz Quartet bandmates, conducted by Lewis, with Bill Evans playing the piano in his stead. In an essay about the film’s music, Martin Myrick cites it as “the ideal founding model for Third Stream scores,” praising Lewis’ blending of classical counterpoint and jazz improvisation. Gunther Schuller, the musician and godfather of Third Stream music, played in the ensemble that recorded the score and commended it for how “it utilizes jazz music as a purely dramatic music to underline a variety of situations not specifically related to jazz… it can serve its purpose in the film but it can also stand as absolute music apart from the original dramatic situation.”

The Modern Jazz Quartet also made a separate, standalone recording of Lewis’ music as well. Here they are performing “Skating In Central Park,” a waltz that was written to accompany Harry Belafonte’s character taking his daughter on an afternoon outing:

The Modern Jazz Quartet performing pianist John Lewis’ “Skating In Central Park,” with Milt Jackson on vibes, Percy Heath on bass, and Connie Kay on drums, from the group’s 1959 album of music from the film Odds Against Tomorrow. The piece would be recorded several years later as well by pianist Bill Evans and guitarist Jim Hall, who were both part of the larger ensemble used by Lewis for the original soundtrack.

Odds Against Tomorrow was a groundbreaking film in several ways. It was the first Hollywood movie with a black producer and the first film noir with a Black protagonist, and John Lewis’ score introduced the Third Stream concept of blending jazz and classical music to soundtrack composition, setting a precedent for David Amram’s work on The Manchurian Candidate and Lalo Schifrin’s TV and movie writing as well. And, along with Duke Ellington’s work the same year on Anatomy Of A Murder, it helped open the door for Black composers in Hollywood.

More About Anatomy Of A Murder

The Story Of Duke Ellington's Anatomy Of A Murder Score

More Duke Ellington On Night Lights

Black, Brown And Beige: Duke Ellington's Historic Jazz Symphony

Swing It Loud: Duke Ellington's Early Black-Pride Music

He, Too, Was America: Duke Ellington's Epic Journey

Ellington Ending: Duke Ellington 1967-73

The Trailers For Anatomy Of A Murder and Odds Against Tomorrow: