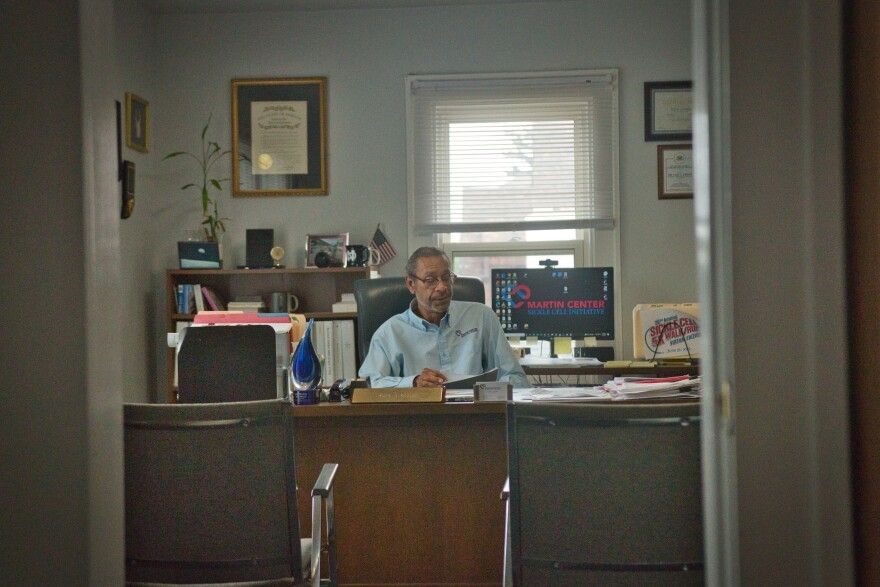

Gary Gibson, CEO of The Martin Center Sickle Cell Initiative in Indianapolis, is the longest serving employee in the nonprofit. His work is focused on filling the social and economic needs of sickle cell disease patients and their families. He is inspired by his wife, Brenda Williams, who died at age 36 from sickle cell disease complications. (Brice Bauer)

Gary Gibson has a clear memory of his first conversation with his future wife Brenda Williams back in 1973.

“Hello, my name is Brenda,” was the first thing Gibson remembers her saying. The second was, “I have sickle cell disease.”

“I was like, sickle what?” Gibson said.

Gibson wasn't sure how flabbergasted he should be. At the time, he didn’t know what sickle cell disease was. But he’d soon find out.

“I'll never forget the very first time that I saw her in crisis. It just tore my heart right out of my chest, to see that,” Gibson said.

Gibson remembers driving for three hours from South Bend, Indiana, to Detroit, Michigan, where Williams went to school at the time, to visit her at the hospital. He imagined an emotional reunion, and maybe a tender embrace that would help soothe Williams’ pain. He rushed to her room, sat down beside her and put his hand on the hospital bed, which caused it to move just a bit.

“She screamed and hollered and said, ‘Don't do that,’ in a very, very strong voice, as strong as she could sound when she was in that kind of pain,” Gibson remembered. “And I was like, ‘Don't do what?’ And she was like, ‘Don't touch the bed, it hurts.’”

Williams had experienced what’s called a pain crisis. Sickle cell disease causes a person’s blood cells to change from their typical doughnut shape to the shape of a banana or a sickle. This makes it harder for the blood to carry oxygen to major organs and can cause strokes, tissue damage and organ failure. Sickled cells also tend to clump together and get stuck inside blood vessels, causing excruciating pain.

“To think about the fact that she was in that much pain, and then to watch how it was tearing her apart, [it] started tearing me apart,” Gibson said.

Sickle cell disease is a genetic disorder that affects nearly 100,000 people in the U.S. It’s the nation’s most common genetic disorder, but is often overlooked when it comes to resources.

The disease receives far less research funding compared to other illnesses, which slows progress in the development of new treatments and medical guidelines that help ensure patients get proper medical care. In many parts of the country, it’s extremely difficult to find doctors who specialize in treating the disease.

The vast majority of people with sickle cell disease are Black. Sickle cell researchers, physicians and patients believe these disparities exist – and persist – because of systemic racism.

‘Sickle cell has taken three lives from me’

In the U.S., about one in 13 Black or African American children is born with the sickle cell trait, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This means they have one copy of the sickle cell gene, which is harmless. But when a person inherits two copies — one from each biological parent — they are born with sickle cell disease. A baby has a 25 percent chance of being born with sickle cell disease if both parents have the trait.

About one out of every 365 Black or African American babies are born with sickle cell disease in the U.S. While sickle cell can affect people from all ethnic backgrounds, the vast majority are Black. One hypothesis for why the illness primarily affects people of African descent considers the prevalence of malaria in certain parts of the world and the fact that the same gene that causes sickle cell offers protection against malaria.

U.S. physicians first understood sickle cell disease over a century ago, when an Illinois doctor observed the blood cells of a Black dentistry student suffering unexplained pains. Quickly, it became labeled a “Black disease” in medical journals. Many experts believe this is why progress and innovation in the treatment of the disease has been slow.

Brenda Williams was part of a clinical trial in the 1980s for the first-ever drug to help manage sickle cell disease. Her health was deteriorating rapidly, and the trial was her only option.

The drug, hydroxyurea, received FDA approval in 1998. Another drug to treat sickle cell disease wouldn’t be approved for nearly two decades.

Williams did not live long enough to see the benefits of either drug. She died at age 36 due to complications from a sickle cell pain crisis.

“She was actually carrying twins when she passed away, and we lost both of them. And so from my standpoint, sickle cell has taken three lives from me, and that’s why I’m a fighter for sickle cell disease,” Gibson said.

Since his wife’s death, Gibson has been active in sickle cell disease advocacy work through The Martin Center Sickle Cell Initiative. It’s been more than 37 years, and he is now CEO of the Indianapolis-based nonprofit. The group provides non-clinical social and financial support for patients and their families. Gibson’s office is lined with pictures of sickle cell disease patients, as well as social justice literature and a big portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr.

For Gibson, this is a social justice and a clinical fight.

“We found that this disease was killing people early and maiming them and causing all kinds of other issues,” Gibson said. “But society said, ‘Who cares? They're Black people, we don't care.’ And I think that that was something that was taking place in the psyche of American society.”

Disparities in funding and access to care

Sickle cell disease patients are often unable to access the care they need for their debilitating disease.

And government and private resources dedicated to it pale in comparison to other diseases.

Sickle cell disease is often compared to cystic fibrosis – another genetic illness that’s similarly complex, but not as common as sickle cell disease. An estimated 30,000 people in the U.S. have cystic fibrosis, compared to about 100,000 sickle cell disease patients. The majority of cystic fibrosis patients are White. Federal funding for research on cystic fibrosis is nearly 10 times higher per patient compared to sickle cell disease.

There’s only one explanation for this federal funding disparity: systemic racism, says Marsha Treadwell, a researcher and a pediatric psychologist specializing in sickle cell disease at Benioff Children’s Hospital at the University of California San Francisco.

She suspects the disparity in philanthropic funding for the two diseases is even greater, because Black people in the U.S. typically have less social capital. One peer-reviewed study found funding from charitable foundations for cystic fibrosis is 75 times greater per patient than for sickle cell disease.

Black Americans have been handed the short end of the stick for generations when it comes to educational opportunities and wealth accumulation. Those who have sickle cell disease on top of that experience a double whammy. The disease is debilitating, making it hard for many of them to complete school, especially under-resourced, majority-Black public schools that often lack proper accommodations. As a result, they are less likely to land well-paying jobs and more likely to end up unemployed due to the unexpected nature of the disease.

“When you think about Blacks and African Americans, you have to understand the relationship between wealth, employment, health and the criminal justice system,” Treadwell said. “It is a very complex relationship in this country. And it does come into play for people with sickle cell disease.”

More than half of all sickle cell patients are on some kind of government insurance programs, like Medicaid and Medicare, which tend to pay health care providers less for services than private insurers

For this reason, fewer doctors choose to specialize in treating sickle cell disease, says Dr. Sophie Lanzkron, the director of the sickle cell center for adults at Johns Hopkins University.

When she seeks reimbursement from Medicaid for care provided to sickle cell patients, Lanzkron said she is paid less than 40 percent of what she bills.

“You can't just put up a shingle and open your door and say, ‘I'm a sickle cell doc’ and expect to make a living. You can't,” Lanzkron said.

It creates a situation where only large academic centers like Hopkins can afford to sustain comprehensive sickle cell disease programs. Compare that, again, to cystic fibrosis: There are more than 100 comprehensive care centers for cystic fibrosis, and fewer than half that many centers for sickle cell disease. That leaves comprehensive care out of reach for most sickle cell patients in the U.S.

The way we treat sickle cell patients today is like telling someone with cancer to get care from a non-specialist or the emergency department – instead of an oncologist.

Lanzkron called it “inadequate and unethical.”

Black pain is discredited and neglected

Teanika Hoffman, 35, has first-hand experience with inadequate care. She’s Black and has sickle cell disease.

When Hoffman was in graduate school, midterm season hit and the pressure and stress of wanting to ace her exams and land on the Dean’s list triggered a pain crisis. She was overcome by pain in her legs.

This was her first sickle cell pain crisis away from her family, navigating care alone as an adult. She managed to get to a nearby hospital in Philadelphia. Things quickly unraveled.

“I was basically ignored in excruciating pain. My health deteriorated really quickly,” Hoffman said. “I could barely move [and felt] super weak. My family had to drive up from Maryland to discharge me against medical advice.”

Hoffman said her family rushed her to another hospital where they “nursed her back to life.” But by that point, her hip bone had died, leaving her unable to walk for a month.

Because Hoffman has sickle cell disease SC (a type of sickle cell disease), her hemoglobin levels are often high compared to other sickle cell patients. During pain crises that land her in the hospital, she said staff would do blood tests, see her hemoglobin levels and start to question if she even has sickle cell disease.

“It’s like taking your finger and like slamming it in your car door repeatedly, right? And then going to the hospital and being told, ‘you're not in pain, you're a liar, you're a drug addict,’ and then sitting hours in excruciating pain and then hoping that someone will take pity on you,” she said.

“This is the story I've noticed throughout my life, you know, being discharged from one hospital to another hospital.”

The onus was on her to prove her sickness — something she suspects she wouldn’t have to do if she were White.

In health care settings, clinical guidelines help inform doctors on the proper care and management of patients with complex illnesses. Some guidelines exist for sickle cell disease, but they’re not consistently followed, said Treadwell, the UCSF psychologist.

A dearth in funding and providers means less research and less data are available. Unlike cystic fibrosis and hemophilia — another less-common genetic blood disorder affecting mostly White patients — sickle cell does not have a national registry that supports nationwide clinical research studies and aggregates findings that help inform guidelines.

This means that even when sickle cell guidelines are updated with new data and information, providers are not always aware of them or inclined to follow them.

“The health care system says, ‘We need evidence for these guidelines that you're putting forward.’ But you can't generate the evidence without proper funding,” she said. “So you have this cycle, again, where there's a demand for evidence before the guidelines are pulled into play, but yet, there's no way to generate the evidence because you just don't have enough funding behind it.”

For diseases like cystic fibrosis and hemophilia, providers in emergency departments have clear guidelines to follow, and specialists are often called on for help.

“When you have cystic fibrosis and you show up in the emergency room in the middle of nowhere, the first phone call is to [your] pulmonologist,” Lanzkron said. “[ER staff] are terrified to do the wrong thing for that person with cystic fibrosis.”

But it’s a different story for sickle cell disease.

Oftentimes when sickle cell patients show up in crisis, they have other complications that can go unrecognized because there is no sickle cell disease expert involved in their care – and specialists are not brought in to help.

Some of these patients end up dying or are left with irreversible damage.

“I've had patients of mine who have had really bad outcomes because no one bothered to pick up the phone,” Lanzkron said.

Farah’s reporting on sickle cell disease is supported by a grant from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.